In 1951, Jaguar moved into a former WW2 shadow factory on Browns Lane, Coventry, where it would build some of the world’s most iconic cars

Words: Paul Walton Images: Paul Walton, Getty Images

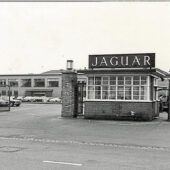

On the western outskirts of Coventry is Browns Lane, Jaguar’s home for half a century. It is an unlikely location for a car factory; lined with red-bricked, semi-detached houses, it is more typical of suburban Britain. But between 1951 and 2005 this leafy street was as important to Britain’s car industry as Maranello is to Italy, or Stuttgart and Munich to Germany. From the D-type to the X100 XK8, Mk VII to the X350 XJ, every great Jaguar from this era was produced here.

Browns Lane isn’t Jaguar’s birthplace, though; that was 150 miles to the north, in Blackpool, where a young William Lyons and his business partner, William Warmsley, started the Swallow Sidecar Company in 1922. Next came coach-built cars, which proved popular due to Lyon’s eye for design. Yet he recognised that the lack of skilled automotive labour in this popular seaside resort would stop him being able to grow his company. He needed to move to the centre of British car manufacturing, the West Midlands.

So, in 1928, Lyons transferred the company (later renamed SS) to the Whitmore Park Estate in Foleshill, to the north of Coventry, and into a double-H block building that offered 5,000sq ft (464sq m) of space. Originally commissioned by the British Government as a reserve shell-filling factory, it had been completed early in the First World War, but left unused. Consequently, it was in a poor state when Lyons’ workers moved in, but, on the plus side, they would be in good company because the Dunlop Rim & Wheel Company and Motor Panels were close neighbours.

With the advent of the Second World War, the company produced aircraft parts here for the war effort. Immediately afterward, Lyons (Warmsley had left in 1935) changed its name to Jaguar.

The first few XK120s were built at Foleshill, as was the Mk V, but their success meant Jaguar soon outgrew the factory as it tried to keep up with demand. When the local council refused to allow Lyons to extend, he looked for an alternative.

The first D-type is built alongside C-types in the competitions department during 1954

In early 1950, and after sending investigative teams to Scotland, Wales and even Northern Ireland, Lyons decided that the solution lay a mere two miles away – a former World War Two shadow factory on Browns Lane, in Allesley. Despite this modern factory (originally built for Daimler to produce the Ferret armoured car) being in a largely residential area, with one million sq ft (992,900sq m) of manufacturing space Lyons thought it ideal. Tough negotiations with Sir Archibald Rowland of the Ministry of Supply followed, during which both parties threatened to walk away, but a deal for the rent was eventually struck: five years fixed at £30,000. Ever the clever businessman, Lyons sold Jaguar’s existing factory to the Dunlop Rim & Wheel Company.

Although production of the Ferret was tailing off, Daimler was slow to move out; it was May 1951 before Jaguar could start to move into the new site. Each weekend, an entire department was moved (the machine shop first, the paint shop last) using lorries borrowed from all over the West Midlands. It turned out to be a long, laborious process and the move wasn’t completed until November 1952.

The shadow factory had included a separate ballroom and a sports club that overlooked Browns Lane itself. To this, a two-story brick building was soon added to contain the reception, staff canteen, administrative office, board room and Sir William’s own office. What had been the ballroom became a showroom of Jaguar’s current models and, later, its growing collection of historic cars (all with drip trays underneath to protect the plush carpet). The building’s big double doors and the wooden façade around them would become the most recognisable part of the site due to the many new models and personnel that were photographed outside.

One of the site’s most famous areas, though, was the competitions department, located in a small, independent building at the north end of the factory and where the D-types and, later, Lightweight E-types were developed and built. In Jaguar’s typical ‘make do’ mentality, it went on to become the experimental department and then Jaguar’s first (and very basic) dedicated styling studio.

The XK120 and Mk VII were largely built by hand and had to be physically pushed throughout the manufacturing process. But, in the mid-50s, the rise of a new, higher-volume small saloon – the eventual 2.4 – would require a mechanised assembly line. Instead of sourcing new equipment, though, Lyons bought a second-hand line from the Standard-Triumph factory (formerly Mulliner) on Torrington Road, on which, among others, the Triumph Herald had been built. He also bought body finishing and painting equipment from the same location, tools that would be used for the next 40 years.

The Mk 2 assembly line in 1964

Browns Lane quickly became one of the most successful post-war factories of the West Midlands, with 10,868 cars sold in 1955, many of which were exported. In recognition of this success, HM Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip visited the factory in March 1956, touring the assembly lines alongside the newly knighted Sir William and Lady Lyons. The book From Foleshill to Browns Lane records how Prince Philip spoke to its author and former Jaguar employee, Brian James Martin, asking what he was doing. “I told him that I was fitting a heater,” writes Martin. “In response to my stammered reply, he said, ‘You are all doing a grand job for England.’ It was as good as a pay rise!”

Yet it all could have come to an end on the evening of 12 February 1957 when a huge fire destroyed large sections of the factory. It began in a tyre store close to the service department in the north of the factory and, despite the rapid response of the fire brigade, it was soon burning uncontrollably. “Half an hour after the alarm was given, at 5.45pm, it was out of our control,” said Bill Cassidy from the experimental department the following day to news reporters. The blaze was finally brought under control in the early hours of the 13th, when its damage could be assessed. Some 14,493sq m (the equivalent of two full-sized football pitches) were affected, and 270 cars. In total, the fire damage cost Jaguar an incredible, and potentially company-crippling, £3.5million.

Thankfully, the fire brigade stopped the flames from destroying the main production line, engine assembly area, machine shop, chroming areas and press shop. Lyons himself had directed the fire-fighting effort to ensure the fire was cut off before it could spread to these sections.

It was with the knowledge that these important areas had been saved that Lyons could say he was confident things would get moving again. He told reporters, “I should imagine we can make a start on a reduced assembly line in a day or so.” He wasn’t wrong.

The clean-up operation started that day. Organised by the service department’s foreman, Jock Thompson, and manager Bill Borbury, the destroyed cars were removed and parked across the factory, even along Browns Lane itself. All the staff worked on clearing the debris, and the damaged areas were soon cleared, allowing the roof to be repaired and car production to restart a mere 36 hours after the fire. By the end of the first week, 93 cars had been built; by April, this had risen to 1,000 and production was back to pre-fire levels.

In fact, 1957 turned out to be a record year for the company, the 12,952 cars beat the previous record, set in 1956, of 800 cars. Even more incredibly, the new 3.4 saloon was launched during this time and a fortnight after the fire more than 200 had been exported to America.

For some time, Lyons had been negotiating with the Government to buy the Browns Lane plant and, in early 1959, his offer of £1.25m was accepted, an achievement that he would later count among his most satisfying.

However, with three successful models (XK150, Mk 2 and Mk IX), by 1960 Jaguar had also outgrown this factory. With Lyons’ request to expand the site declined and the company too large to move in the way it had done a decade before, Lyons instead bought Daimler to get access to its own one million sq ft factory in Radford, which, for the next four decades, would be Jaguar’s engine plant and engineering centre. Browns Lane’s role in the company, once an extra track had been added, was to focus purely on assembly, rather than manufacturing.

In 1966, Jaguar was taken over by BMC, forming British Motor Holdings Limited (BMH) which, in turn, became British Leyland following its merger with Leyland Motors in 1968. No longer independent, this was the start of a rocky two decades for both the company and its factory.

By the early 70s, Browns Lane had become badly neglected due to little or no investment for years. “In some ways it was a bit of a shock because it did feel quite run-down, old and slightly has-been,” says former designer Keith Helfet, who joined the company in 1978. Still using the same assembly track Lyons had bought in the Fifties, plus ancient tooling, the quality of Jaguar cars – and, therefore, Jaguar’s image – suffered badly throughout the decade. As Geoffrey Robinson (Jaguar’s chairman for two years from 1973) remarked, “Bill Lyons wanted a first-class bodyshell off third-class tooling.” By 1975, production was down to 21,752 cars, a big drop from the 31,549 of just four years earlier.

Sir William Lyons outside the Browns Lane office block in the early 60s, with products produced by the Jaguar Group

Not long after Robinson took over the reins, he laid out an ambitious plan for the factory’s expansion to include a new manufacturing facility to house a modern paint shop that would be surrounded by a test track. To support the necessary planning, a new entrance was envisaged to lessen the amount of traffic down Browns Lane itself, to appease those who lived there. But these plans were soon scrapped. Following a report by Sir Don Ryder (the newly appointed head of the UK’s National Enterprise Board) with recommendations to make the then-ailing Leyland more productive, it was decided a new paint shop should instead be located at Leyland’s Castle Bromwich plant in Birmingham, another former WW2 shadow factory that was already producing the bodyshells for Jaguar’s cars.

One of Ryder’s most important recommendations was to remove autonomy of the individual brands and for Leyland to rationalise its many resources. Read the report, “BL cannot compete successfully as a producer of cars unless it can make the most effective use of all its design, engineering, manufacturing and marketing resources.” As a result, in 1977, Jaguar’s Browns Lane factory was renamed ‘Large car plant number 2’. To further rub salt into the wound, British Leyland required the removal of all Jaguar signage at the site and the company colour was changed from racing green to British Leyland’s universal white and blue. Jaguar’s loyal staff were so outraged by this that the Browns Lane plant director instigated the careful removal and storage (even at workers’ homes) of everything displaying Jaguar’s name or image.

Despite Leyland’s attempt to erase Jaguar’s identity, its heritage meant that even in the Seventies the factory had a unique aura. Keith Helfet explains, “Being the petrolhead I was then, I loved the fact that on that site wonderful things had happened and clever people had been doing brilliant things. For example, our styling studio had been the competitions shop, where the racing cars had been built.”

But the poor reputation of its cars, a striking workforce, and regular energy shortages that stopped production, meant that by 1979 Browns Lane was down to producing a mere 14,283 cars. Thankfully, help was coming.

In 1980, former Massey Ferguson director (Sir) John Egan was appointed as chairman. Not only did he solve many of the workers’ issues, but he also oversaw investment in the facilities. An increase of sales naturally followed – 33,437 in 1984 – which resulted in Jaguar’s privatisation the same year, allowing Jaguar to break free of Leyland and make its own decisions for the first time in almost two decades.

That freedom didn’t last long, though, because five years later the company was bought by Ford. After paying 1.6billion, Ford’s executives were shocked by the poor state of Jaguar’s facilities, Browns Lane especially. As Alex Trotman, then Ford of Europe chairman and integral to the company’s takeover, said years later, “There was nothing wrong with Jaguar manufacturing that a bulldozer wouldn’t fix.”

XJ-S production in the mid 80s

As an example of the problems Ford faced, shortly after new chairman Nick Scheele had arrived at Jaguar in 1992, he went to the water booth where cars were tested for leaks; new models were scoring in the 90s. Scheele had spent much of his career working for Ford on the other side of the Atlantic and, according to American practice whereby results were scored on a scale of 100, that seemed to Scheele to be a good result. But the test engineer pointed out that, at Jaguar, the figure meant the vehicle had 90 leaks.

Consequently, over a three-week period in August 1993, the Browns Lane assembly plant received a £8.5m refit that replaced the ancient, ex-Triumph assembly line with modern equipment. As the quality of the cars improved, so did sales; in 1992, Browns Lane had produced a mere 22,499 cars, but just six years later this figure had increased to 50,225. In 2000, as vindication to the scale of improvements made, the respected American research firm JD Power gave the Browns Lane factory first place in its European plant awards.

In 1999, production of Jaguar’s new executive car, the S-Type, started at Castle Bromwich (which had been under Jaguar’s control since 1980). This was followed by the X-Type in 2002 at Ford’s Halewood plant (it had previously produced the Escort). Production moving to these factories would later facilitate the closure of Browns Lane.

By the early 2000s, both the company and its American parent were making serious losses – in 2004, Ford reported a second-quarter pre-tax loss for its Premier Automotive Group of $362million, with an estimated $178million attributed to Jaguar. Part of the problem was producing cars in three locations. For volume car manufacturers at the time, 300,000 was the optimum annual production for one plant, but, in 2003, Jaguar had produced just 120,000 at three. In need of the most investment and with the least room for expansion, Browns Lane was earmarked for closure, which Jaguar’s chairman, Joe Greenwell, announced in September 2004. “It is not a decision we have taken lightly,” he said. “We do have a strong attachment to Browns Lane, but it does not have the infrastructural advantages of other plants.” He later told MPs on the Trade and Industry Select Committee that to continue producing 120,000-cars-a-year at three plants was, “A recipe for the end of Jaguar. “Unless we follow this path, the future viability of the company is at risk, as are the jobs of 8,000 people.”

Still, 1,100 jobs were cut, prompting demonstrations by Jaguar workers and union members to keep the factory open. “This is a bleak day for the British car industry,” said Tony Woodley, general secretary of the T&G Union, while Derek Simpson, general secretary of the Amicus Trade Union, believed, “Ford’s decision may kill off Jaguar. Our members will fight like tigers to keep the lion’s share of quality car manufacturing in Britain.”

Workers and union members demonstrate against the proposed closure of Browns Lane

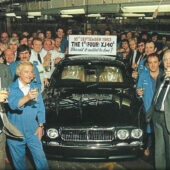

Their protests were ultimately unsuccessful. On 1 July 2005, the final car – an XJ Super V8 Portfolio – rolled off the Browns Lane assembly line. It was the 1,447,677th car to have been built at the plant between 1952 and 2005 (a tiny figure compared to the numbers BMW’s vast Munich factory, or Volkswagen’s enormous Wolfsburg facility, produced at the time). Production of the saloon moved to Castle Bromwich, where it joined the S-Type and new X150 generation of XK.

“This is a huge emotional blow to Coventry,” said Nick Matthews of the Warwick Manufacturing Group at Warwick University. “Jaguar is in Coventry’s DNA and vice versa. It is like losing a friend or a member of family.”

The 117-acre site was eventually sold in 2007 to Australian developer Macquarie Goodman, and the historic assembly and administrative buildings were demolished the followed year. A housing development called Swallows Nest and Lyons Park Industrial Estate now occupy the area, the latter home to the Technology Centre, where clients include Jaguar Land Rover.

Today, Jaguar is a global business with manufacturing facilities all over the world, but its long association with Browns Lane and the many iconic models produced there means for many it will always be the company’s spiritual home.