It may be considered the black sheep of the modern Porsche engine family, but the 718 Boxster’s turbocharged B4 flat-four is worth a closer look

Words: Shane O’Donoghue

Porsche began 2016 with the bombshell announcement that the new Boxster would be powered by a turbocharged four-cylinder engine (factory code B4). Not long after, I got my first chance to sample the new 718-generation roadster on UK asphalt. This was before Porsche’s embargo restricting publication of driving impressions after the manufacturer’s model launch had lifted. In other words, I hadn’t yet read any reports from elsewhere in the motoring press, which meant there was no danger my opinion of the 718 would be clouded by the verdict of others.

After a couple of hours at the wheel, I declared the new Boxster a triumph, eclipsing its predecessor in almost every way and, while I conceded the flat-four engine was nowhere near as melodic as the flat-six forerunner, I also concluded it helped distance the 718 from the 911, giving the mid-engined model a unique personality. Job done, no need for any other sportscar maker to bother trying.

Not long after, the embargo was over and reviews surfaced. While most agreed with my assessment of the core car, many were vociferous in their condemnation of the new engine. That bud of criticism soon grew into a tree of discontent, which is why now, once again, we have a glorious naturally aspirated flat-six in the middle of the 718. Did Porsche fail to ‘read the room’ correctly? Was I so intoxicated by the 718 Boxster’s chassis that I turned a blind eye (ear?) to what colleagues were suggesting were the B4 engine’s failings? Sure, I tested the more powerful Boxster S, replete with a sports exhaust, but still…

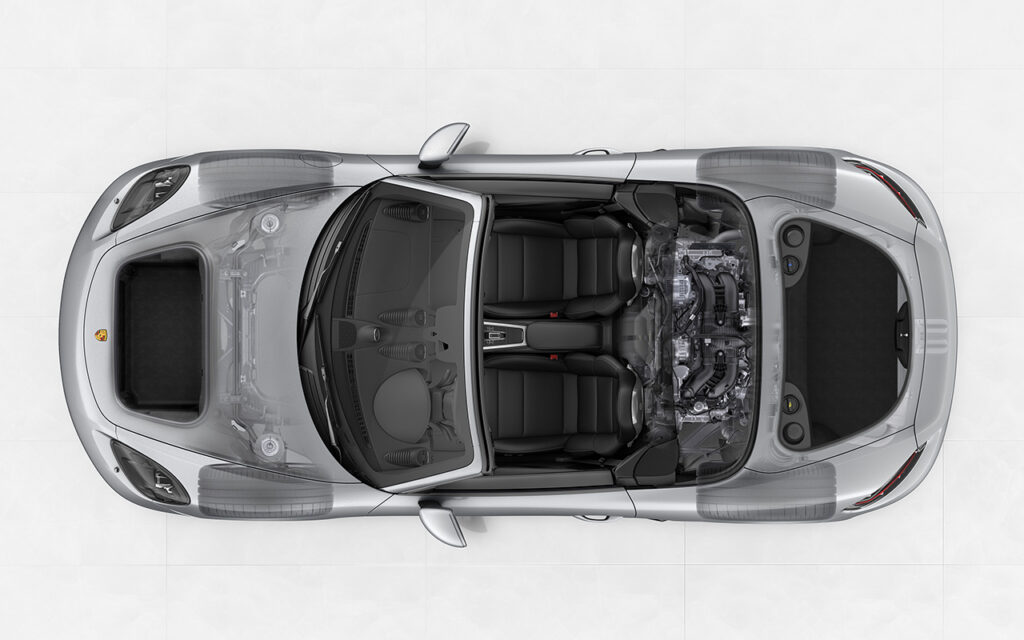

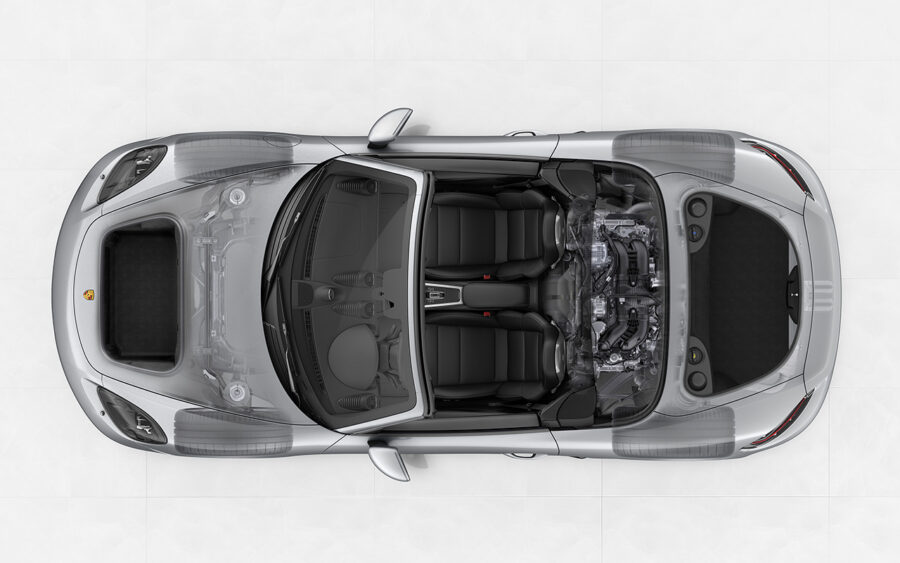

Thing is, four-cylinder engines have a big part to play in Porsche’s history, powering the 356, 912, 914, 924, 944 and 968, plus many of the manufacturer’s classic racing machines. Indeed, a flat-four was central to the first three of the production models I’ve mentioned, as it was to the original 718 of the late 1950s. With all that heritage to play on, it made a lot of sense to revive the flat-four boxer for the modern day. Of course, the real reason for its reinvention was to enhance the efficiency of Porsche’s mid-engined Boxster/Cayman twins, maintaining their weight, emissions and fuel consumption while, thanks to the addition of turbocharging, significantly enhancing the performance potential.

At launch, the range-topper was listed as the 718 Boxster S, powered by a 2.5-litre version of the new B4 engine. At 345bhp and 310lb-ft torque, peak outputs of this unit are impressive enough — representing useful jumps over the previous Boxster S’s 311bhp and 265lb-ft — but they hide the fact the new engine produces substantially more torque across the entire rev range. Where the old flat-six’s torque initially climbs close to 243lb-ft at 2,500rpm, then peters out, then climbs again to its peak at 4,500rpm, the flat-four surpasses it. Indeed, the 2.5-litre engine rapidly gets to its (higher) maximum torque at just 1,900rpm and keeps on delivering it all the way to 4,500rpm. From there it tails off, but even when the rev limiter kicks in at 7,500rpm, it’s still producing near 15lb-ft more than the naturally aspirated unit could manage.

In short, the turbocharged flat-four eclipses its predecessor in the performance stakes: the 718 Boxster S equipped with PDK manages 0-62mph in 4.2 seconds and 0-124mph in 14.7 seconds, knocking 0.6 seconds and 2.6 seconds, respectively, from the same measurements in the earlier Boxster S PDK. The 718 smashes its predecessor’s 62-124mph time by nearly five seconds, too. Perhaps surprisingly, the two-litre engined 718 Boxster makes bigger gains again than its predecessor.

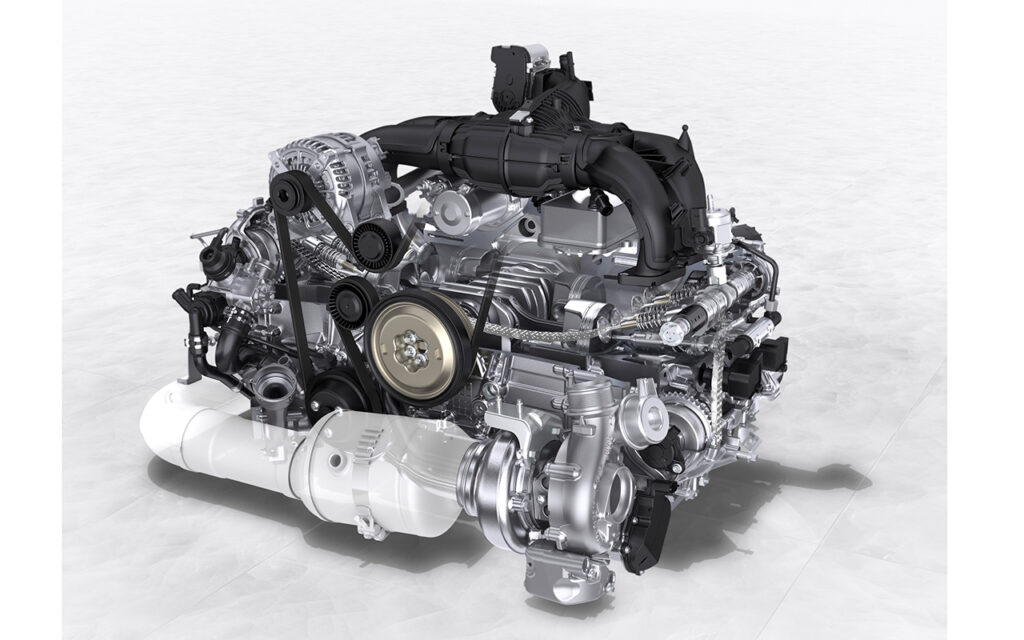

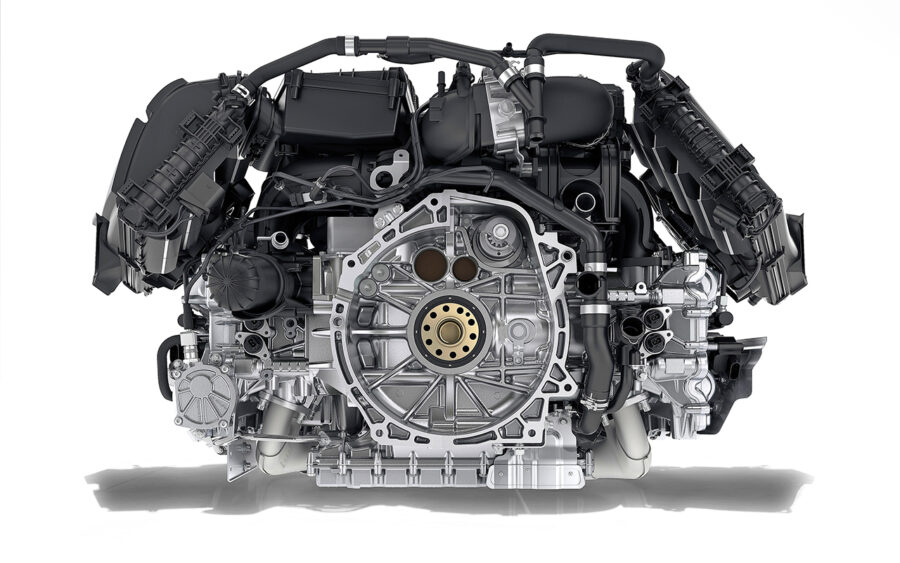

Both engine displacements use a 76.4mm stroke (which is the same as the turbocharged three-litre B6 engine loaded into the back of the 991-generation 911) and a 9.5:1 compression ratio. The difference in swept volume between the 718 engines comes from the bore diameters, measuring 91mm in the two-litre (again, the same as that of the three-litre 991 engine, though the pistons are different) and 102mm in the 2.5-litre unit. That’s not the only dissimilarity, however, as these engines use different turbocharging concepts, too: the standard 718 Boxster’s setup is straightforward, employing a 50mm turbine wheel diameter, 58mm compressor wheel diameter and a wastegate to control maximum charge pressure to 1.4bar, while the 718 Boxster S makes use of Variable Turbine Geometry (VTG) technology, which was already employed to great effect on the contemporary 911 Turbo.

The turbine wheel diameter, at 55mm, isn’t much bigger than that of the turbocharger in the two-litre car, but at 64mm, the compressor wheel diameter is much wider. Its biggest trick, however, is to physically alter the shape of the inlet to the turbine, depending on the speed of the exhaust flow. More specifically, at low speeds and loads, vanes positioned around the circumference pivot to reduce the space between each one. This has the effect of speeding up exhaust gases before they hit the turbine vanes, allowing the turbocharger to spin quickly, even when flow speed is low. Then, when the engine revs or load increase, and the flow rate of exhaust gases does likewise, the vanes pivot the other way, opening the pathway to the turbine inside for maximum boost. Once you begin to understand how effective VTG can be, you realise how compromised a turbocharger without this feature really is. Incidentally, the 2.5-litre flat-four’s turbo produces up to 1.0bar of boost for the 718 Boxster S.

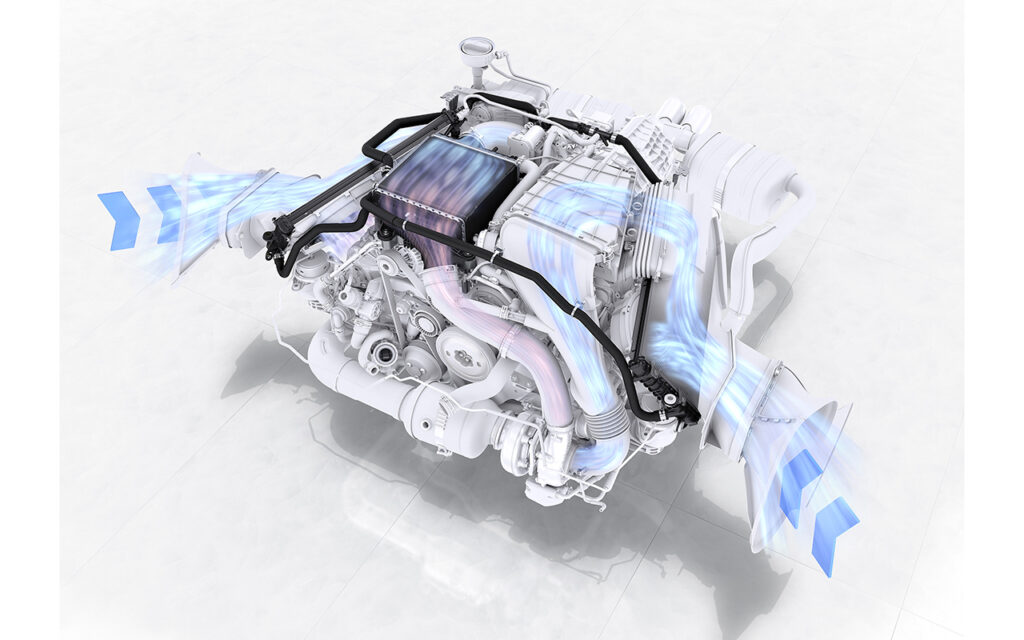

There’s no point producing all that lovely, pressurised intake air on the compressor side of the turbocharger if it’s so hot combustion is compromised by the need to retard spark ignition as a means of avoiding knock. Intercooling of the combustion air after it has been compressed by the turbo is the now the norm, with turbocharged 911 engines making use of air-to-air intercoolers. This would, however, usually require additional air inlets for the intercooler — a problem when Porsche was adamant the 718 would maintain its core aesthetic.

Instead, the company’s engineers came up with a clever ‘indirect’ intercooling setup, requiring only a minimal increase in the size of the air intakes ahead of the Boxster’s rear wheels.

By way of the left-hand intake, the engine sucks air through a filter and on through the turbocharger. The compressor wheel pressurises the air, but in doing so, increases its temperature to as high as 170°C. This air is fed into a new heat exchanger located on top of the engine, which transfers heat from the air into water-based coolant as part of a ‘low temperature’ circuit that’s separate, but uses the same reservoir as the main engine coolant. The hot water then flows into the two laterally positioned engine radiators to be cooled as normal.

The result is consistent access to the performance figures detailed earlier. Looking at a wide-open throttle plot of engine revs versus torque output is one thing, and flat-out straight-line acceleration is another, but the fact all this translates into tangibly greater performance more of the time is undeniable, even after only the briefest of drives in a 718 Boxster. The force-fed B4 flat-four doesn’t need revs to be ballistically quick and yet, as was Porsche’s intention from the start of development, it revs with urgency.

Relatively speaking, that was the easy part, as the shorter crankshaft and lighter engine components meant it was comparatively simple to maintain a high rev limit. The tricky part was giving this turbocharged engine the responsiveness of a naturally aspirated unit. For that, Porsche needed an anti-lag system. If you’re familiar with the term, it’ll likely conjure up images of flame-spitting rally cars accompanied by the distinctive ear-splitting staccato from their exhausts on overrun. In that scenario, air is injected into a fuel-rich exhaust stream to cause combustion in the exhaust manifold, used to keep the turbocharger spinning. Such a system might have been a little anti-social for a road car, never mind the fact that it uses more fuel, somewhat negating one of the main reasons for Porsche producing the new engine! Instead, the manufacturer came up with its Dynamic Boost function, a rather elegant alternative.

When the driver is pushing on and takes their foot off the accelerator, the engine management system cuts fuel as usual, but doesn’t shut the throttle, allowing air to be pumped through the engine and out of the exhaust. The wastegate of the turbocharger is closed to ensure maximum air flow through the turbo, which slows down the rate at which it decelerates and then, when the driver gets back on the power, the turbo is closer to operating speed than it would have been without this airflow. It really is that simple. In Sport mode, this is accompanied by ‘lazier’ cutting of the fuel, in a bid to induce artificial (but lots of fun) pops and bangs in the exhaust when you lift off, though the serious engineers were clearly responsible for the Sport Plus setting, as no such shenanigans occur and the system is optimised to provide flow through the turbo for maximum responsiveness. In a car equipped with

PDK and loaded with the Sport Chrono Package, this function is also called upon when the driver chooses to press the Sport Response button, priming the turbocharger for maximum performance.

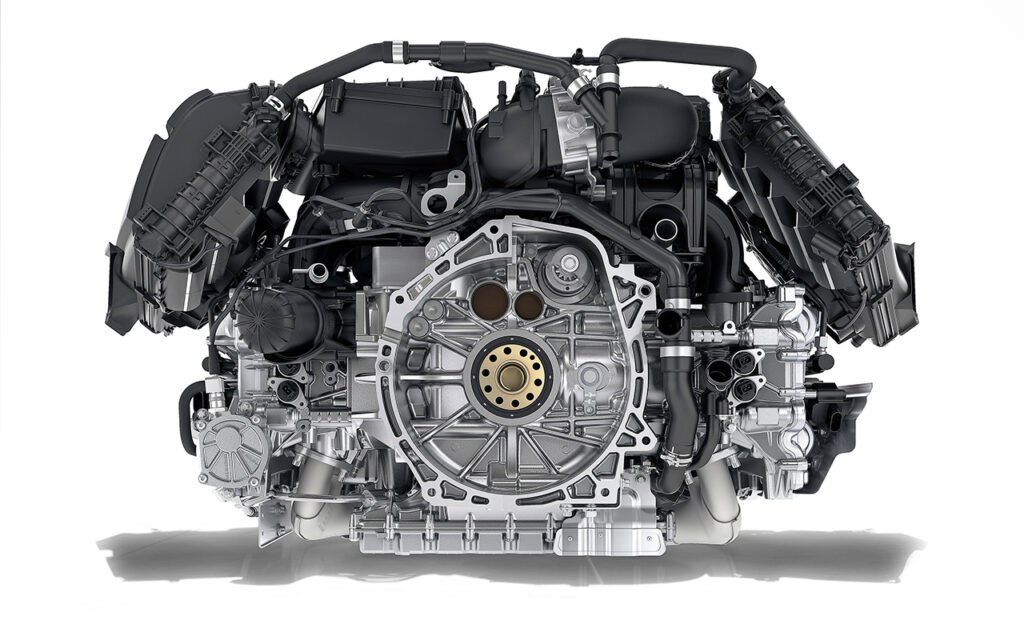

It’s easy to ignore the rest of the engine and focus on the turbocharging system, but there’s a lot more happening here. Not least the fact the flat-four shares a massive number of components with its turbocharged flat-six sibling. You know, the one found in the back of the 911! The list includes the high-pressure direct fuel injection system, the timing chain, almost the entire auxiliary drive, connecting rods, bearings and, in the case of the 718 Boxster’s two-litre B4 engine, even the inlet valves. The flat-four also uses the same technology when it comes to materials and manufacturing of the crankcase and cylinder liners.

There are, however, some significant differences. All 718s make use of adaptive engine mounts, for example, replacing the previous singular forward engine mount with two hydraulic items. As standard, they use engine vacuum to switch between two levels of stiffness, though this can be upgraded to more sophisticated magnetorheological operation if the Sport Chrono Package is fitted. The new dual-mass flywheel has also been designed to balance out the vibrations of the engine at lower speeds, with a centrifugal pendulum.

The 718’s oil sump is aluminium, while the part is plastic on the 911, a difference dictated by the former’s hotter exhaust routing. Then, while the variable demand oil pump in the B6 engine is taken as a basis for that of the flat-four, the smaller engine’s part features two levels of delivery to the B6’s three, reducing the number of components and, consequently, weight.

Porsche went the other way when it came to the control of valves and camshafts, adding sophistication: the flat-four gets VarioCam Plus for complete control of valve timing, as well as two switchable cam profiles for the intake. This is the same as the 911, but in 718 flat-four applications, there’s are also two switchable cam profiles for the exhaust side, allowing calibration to optimise performance or economy, as conditions demand.

Porsche B4 Efficiency and economy

And what of the B4 engine’s efficiency? Well, when it was launched, Porsche quoted a significant thirteen percent improvement in economy and emissions over what came before. Interestingly, that measurement was given on the old NEDC test regime, which has been shown to vary considerably from real-world conditions. Many miles have been driven in turbocharged four-cylinder 718s since that time and it’s generally accepted the newer powerplant is only marginally more economical than its six-cylinder predecessor when driven in normal traffic. Push on and the flat-four is just as thirsty, sometimes more so! It’s worth mentioning, however, that despite a weight decrease in the engine department, the 718 models weighed slightly more than their predecessors, chiefly due to added equipment and beefing up of the brakes.

Nonetheless, as alluded to earlier, the Boxster’s talents when powered by this fantastic B4 flat-four come to the fore when you drive the host 718 in a variety of conditions. And the engine’s ability to cover challenging ground quickly is underscored by the time Porsche quotes for it to lap the Nürburgring Nordschleife: in comparable specification, the B4-kitted 718 Boxster lapped a full sixteen seconds faster than its predecessor.

Nürburgring lap times are, in reality, entirely meaningless when discussing a car designed for street use; driver engagement is perhaps more important than anything else when it comes to a sports car. But anyone who has been lucky enough to drive a modern, four-cylinder 718 won’t complain about the lack of involvement, no matter what they think of the engine note. If Porsche did anything wrong in the rolling out of the B4 unit, it was to allow logic and rationale slightly overshadow emotion — rest assured, by any measure, the turbocharged flat-four is a special engine and there are few finer ways to attack a British B-road.