Based on a 1966 DB6 but converted in the 90s, this modern interpretation of an Aston Martin DBR2 is as close to the real thing as a re-creation can get

Words and images: Paul Walton

As I floor the pedal hard, the action resulting in a strong, sudden and violent burst of speed, I have an immediate sense of what Sir Stirling Moss, Roy Salvadori and many other legendary Aston Martin drivers must have experienced during the 1950s. But it’s not just the speed or handling that’s causing this – as a replica of an Aston Martin DBR2, those aspects of the car are a given – but by the distinctive aroma coming into the cockpit.

Although I’ve never driven a genuine DBR2 before, I have driven other 50s racing cars including a Jaguar C- and D-type and they both had the same unique smell of burnt oil and petrol as this one, making it more than anything, feel like it’s the real thing.

The reason for the aromatic accuracy is simple; although hand-built in the early Nineties, this fabulous re-creation of one of Aston Martin’s most famous racers is heavily based on a 1966 Aston Martin DB6 saloon (including its original running gear) meaning, mechanically at least, it gets as close to the real thing as any re-creation can get. And I’m not just talking about the smell.

The donor vehicle was a 1966 right-hand-drive DB6 saloon, chassis DB62757/L, that was originally bought by a Los Angeles-based film director. He used the DB6 for a short time while living and working in the UK, returning the car to Newport Pagnell for its first service at 500 miles. The Aston was then shipped to America where it was involved in a series of accidents over several years that resulted in the body being removed. In the late Eighties the running chassis was transported to New Zealand to be turned into one of five re-creations of the Aston Martin DBR2 by Tempero, a specialist in building replicas of 50s and 60s racing cars.

On the face of it the DBR2 was perhaps an unusual choice for a replica since only two genuine examples were produced and in terms of results it wasn’t as successful as the earlier DBR1. Yet victories aren’t everything and the DBR2 was also one of the best-looking endurance racing cars from the late 1950s.

Based on the same chassis as the Lagonda 166 V12-engined racing car from 1955, it was instead powered by the new Tadek Marek-designed 3.7-litre straight-six and featured the same suspension as the DBR1.

The DBR2 made its competition debut at the 1957 24 Hours of Le Mans in June, but the sole example retired after eight hours because of gearbox failure. In September the same year, this first car together with a newly completed second were entered into the Daily Express Trophy meeting at Silverstone. In the hands of Roy Salvadori, the second car – now called DBR2/2 –finished first while Noël Cunningham-Reid in the first car – DBR2/1 – as two places behind.

“It was a very pleasant car to drive,” wrote Roy Salvadori in his 1985 biography, Racing Driver, “with the reliable five-speed gearbox unit with the engine, it was possible to turn in really quick laps without feeling the car was being pushed too hard.”

Due to new rules introduced by motorsport’s governing body, the FIA, for the 1958 season that outlawed engines over 3.0 litres, the DBR2 was relegated to non-championship races. With their engines now increased to 3.9 litres, the highlights from this period include Stirling Moss winning that year’s Goodwood Sussex Trophy plus the Oulton Park British Empire Trophy. Both cars were then shipped to America for the 1959 season when their engines were enlarged to 4.2 litres.

But with the DBR1’s racing programme taking up most of the team’s time, the DBR2 wasn’t as well developed as it perhaps should have been and was often outperformed by the competition. “The poor old DBR2,” wrote Stirling Moss in his 1987 biography, My Cars, My Career, about the time he raced one in the Los Angeles Times Grand Prix at Riverside, California. “Despite its enlarged engine, the car was completely outclassed. It pulled 149mph on a 3.25:1 back axle in practice, against Richie Ginther’s older 4.1 Ferrari pulling 165!”

The DBR2 project came to an end when Aston Martin announced it was pulling out of sports car racing in late 1959 to concentrate on its ill-fated Formula One effort the following year. The two examples were subsequently sold but survive and are regularly seen at historic events on both sides of the Atlantic.

This fascinating history together with its handsome lines makes the DBR2 a favourite for companies like Tempero that has its origins in a coachbuilding firm started by Errol Tempero in 1949.

According to his grandson, Rod Tempero, four of the replicas (including the one based on DB62757/L) were commissioned by the-now defunct Fine Sports Cars, a classic car specialist based in La Jolla, California, while the fifth was for an Australian customer. Rod also tells me that Fine Sports Cars – founded by former professional racing driver, Bill Freeman – supplied the chassis that were a mix of the DB5, DB6 and DBS.

Although the fate of the others isn’t known, Rod says when the re-creation based on DB62757/L was finished in 1993 it was sent back to the US when it became part of a large collection of classic cars owned by former navy pilot and millionaire industrialist, Robert Pond. “I always had three cars when I needed one, and six cars when I needed two,” said Pond during a 1999 interview, “and now today I have 100 cars and I need one, but these are the cars that I love.”

When Pond passed away in 2008, his collection was sold and the DBR2 was bought by another enthusiast, Gary Faulds from Montana. Occasionally using it to take his kids to school, he fitted a taller Perspex screen which was later removed.

In preparation to sell the car, in 2011, Faulds sent the DBR2 to a California-based racing car specialist, Virtuoso Performance, spending around $40k to make it more roadworthy which included fitting a middle silencer and quieter exhaust. The ignition was replaced with an MSD unit including a rev-limiter, the starter was swapped for a high-torque unit to ensure starting in extreme conditions and the brake system was completely rebuilt including calipers, master cylinders and flexi-hoses.

It was in 2012 when an advert for the car caught the eye of current owner and long-term Aston enthusiast, Ron Powell, who flew over to California, where it was for sale, to inspect and subsequently buy the car.

Although Ron was living and working in Abu Dhabi at the time, he had the replica shipped to the UK and delivered to established marque specialist, Aston Workshop, in his native north-east of England. The first change he asked for was to have the exhaust replaced with something more suitable.

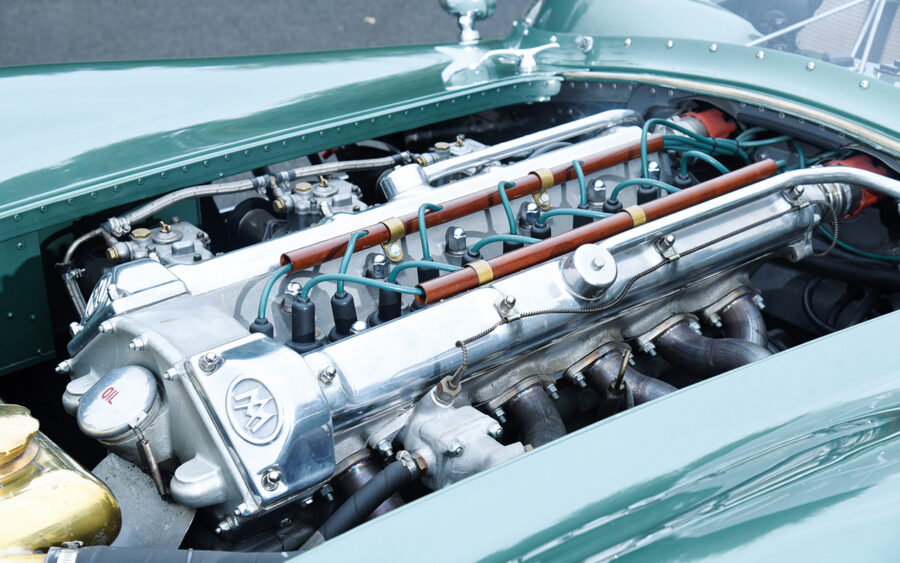

Whenever he drove the car, Ron would often hear a rattle which was eventually traced to damage to the cylinder’s skirts, caused by water getting into the block. Since the engine needed to be rebuilt anyway, the capacity of the DB6’s original 3.7 litres was increased to 4.2.

The car was later involved in a minor accident which damaged the offside rear corner. Although disappointed, it also gave Ron the opportunity to resolve a couple of small issues.

With Aston Workshop in charge of the repairs, the chassis was sent to established racing car restorer, R&J Simpson of Tamworth, to have the damaged corner rebuilt while Clive Smart of Shapecraft in Northampton looked after the aluminium body. Due to previously rebuilding DBR2/1 for its owner, Anthony Bamford, Clive reckoned the front grille of Ron’s car wasn’t totally accurate so he reshaped it at the same time, making it more representative of the real thing.

When Ron bought the DBR2 re-creation – now officially described in its British registration document as a ‘DB6 Roadster’ – it was in an incorrect shade of dark green. After much research, it was repainted in Aston Martin Racing Sage Green, circa 1958.

The post-accident rebuild took almost a year to complete, but once finished Ron has used the car regularly at events in both the UK and Abu Dhabi – including a trackday at the Yas Marina F1 Grand Prix Circuit – and many who see the re-creation often mistake it for the real thing.

Despite knowing the car’s background, even I need to ask Ron if it’s definitely not genuine when we meet at Aston Workshop where the car is having some minor remedial work. It’s not just the inch-perfect shape, evocative colour or exact detailing that makes me think this, but by sitting on the correct Ruote Borrani wire wheels that Ron replaced the Borranis it came with, it has the same imposing stance as a genuine DBR2.

Considering the time and effort it’s taken to get the car to this condition, I’m not just honoured when Ron offers me a drive, but also excited and a little daunted too. It might not be the real thing but with Ron reckoning the 4.2-litre engine produces around 310-320bhp yet with the car weighing a mere 925kg, it still promises to be just as formidable as the genuine Jaguar models I mentioned at the start.

After opening the flimsy aluminium door, I swing my left and then right legs over the wide sill before easing my way down behind the large wood-rimmed steering wheel. The interior is as per a genuine DBR2; stark, basic and with few, if any, creature comforts. The dash is dominated by a huge white-on-black Smiths rev-counter in front of me with the minor dials scattered down the length of the black-painted aluminium. The feeling that the car was constructed in the Fifties rather than the Nineties is further heightened by the switches marked with the same style of embossed Dymo labels as every other Fifties and Sixties racing car I’ve driven. The only concession to modernity is a speedo mounted on the top of the dash which I’ll no doubt need, plus a bright red kill switch underneath that I hope I won’t.

The 4.2-litre engine starts instantly, a loud, noticeable bark erupting from the exhaust as it does so. In September 2015 the car was returned to Aston Workshop to have a multi-branch manifold and side-mounted exhaust designed and fitted with what Ron describes as, “for track use but with consideration to sound and noise levels”. At the same time, a twin spark plug head and high-compression pistons were also added.

Beneath the new racier body, the car still uses the same running gear as the donor DB6 including the five-speed gearbox, so I’m pleasantly surprised to discover how easy it is to slot into first and then pull away. But with an empty road ahead of me, when I gently squeeze the throttle it throws me forward with a hard, noisy and violent acceleration that’s both shocking but also addictive. Although I’m sure a hot hatch would be quicker, the immediacy of the engine’s reaction together with the exposure of the open cockpit and yes, that distinctive smell of a classic engine when hot, makes the car much more of an experience than any modern car.

The five-speed transmission is stiff but precise and I soon learn that the rougher I am, the better the changes. With a little practice I’m soon snicking the short, angled lever down into third, balancing the throttle through a long bend before nailing the throttle at the exit. As the car immediately accelerates in a noisy blast of burnt fuel, I’m no longer in County Durham but transported to France and the famed Circuit de la Sarthe for the 1957 24 Hours of Le Mans.

Through the huge wheel, the steering is as precise as any 1950s-style of sports car based on a 1960s GT can be which is largely accurate but can occasionally suffer from a little vagueness. Yet I’m still able to scythe effortlessly through bends with the same confidence as Roy Salvadori obviously had at Silverstone.

Following an all-too-brief drive, it’s time to head back to Aston Workshop’s premises where I reluctantly hand the car over to Ron. Although its performance can be shockingly hard, needing all my powers of concentration to keep it out of the nearest ditch, it can also be surprisingly easy too, no doubt the result of its DB6 origins.

I may not be a legendary Aston Martin driver like those who piloted the original DBR2 were, but thanks to the easy way in which this well-engineered re-creation delivers its huge amounts of power, I now feel – and certainly smell – as if I am.