Is the new Porsche 911 Dakar anything more than an expensive collector item? We strapped in to find out

Words: Shane O’Donoghue Photography: Barry Hayden

You don’t have to be a dyed-in-the-wool Porschephile to understand the significance of the livery covering the 911 pictured on these pages. Indeed, most motorsport fans will realise it harks back to the Rothmans graphics used on a wide variety of competition cars in the 1980s. It’ll take a little specialist knowledge, however, to know the number our star Porsche carries on its doors is a nod to the Type 953, the manufacturer’s first four-wheel drive 911.

These days, there’s nothing unusual about a supercar with all-wheel drive and a twin-turbocharged engine. In fact, it’s not just supercars relying on the advantages of four-wheel drive — it’s the blueprint for many performance cars, from sports coupes to super saloons, not to mention high-performance SUVs. All-pawed performance wasn’t the norm at the dawn of the 1980s, however, which is why Porsche set the template for the future of high-output motoring when it revealed its Gruppe B concept at the 1983 Frankfurt Motor Show.

This particular design study took an excruciating three years before it was ready for series production, effectively missing its chance to shine as a Group B motorsport weapon, but the resulting 959 deservedly remains one of the most influential cars the world has ever seen. One of the reasons the 959 took so long to come to fruition, of course, was Porsche’s development of then new electronic systems needed to realise the model’s true performance potential.

Adding to the complexity, this was a car intended to push the boundaries of automotive technology, yet it needed to maintain Porsche’s reputation for reliability. Additionally, while supercar performance was a prerequisite, the 959 had to cruise comfortably. It also had to be easy to drive (at all speeds), whilst thrill its occupants with exciting chassis dynamics. On the latter count, all-wheel drive was deemed essential.

It can be argued the idea of all-wheel drive in a Porsche preceded that of the 959. Factory engineering supremo, Helmuth Bott, held back on his designs for an all-wheel drive, open-top 911 until company chairman, Ernst Fuhrmann (a man known to be considering the 911’s end of production), left the business in 1980. Bott convinced incoming boss, Peter Schutz, to allow him free rein on the development of the 911 Cabriolet, as well as a significant evolution of the 911 capable of competing under the FIA’s newly formed Group B regulations. The Gruppe B design study was immediately prepared, but as far as turning it into a production model was concerned, there was a huge amount of work to do.

To help prove the reliability and usefulness of Bott’s dreamed-of all-wheel-drive system, Porsche created the Type 953, often referred to as the 911 4×4. This was a high-riding rally raid special, built specifically to compete in the 1984 Paris-Dakar Rally. There was no requirement for homologation at this event, making it an easy proving ground for new technology in the heat of competition. Interestingly, Porsche stuck with a tried-and-tested normally aspirated 3.2-litre air-cooled flat-six for the 953, going so far as reducing the compression ratio to enable use of local low-octane fuel. The engine produced a modest 221bhp, output indicating Porsche’s priority: to test new hardware driving the wheels.

Details of the initial system are not publicly documented, but we do know the 953 featured a manually operated centre locking differential, which would have allowed the driver to lock the front and rear axles at the same speed, presumably to get the car through deep sand or mud. The 953 also featured a double wishbone front suspension design with two dampers on each side, all of which found its way into the 959. This configuration contributed to the 953’s Paris-Dakar win at the hands of René Metge, who beat Patrick Zanirolli and his Range Rover V8 to the top spot.

Those are big off-road tyres to fill, which may lead many of you to suspect the new 911 Dakar is little more than a cynical marketing exercise, hanging off the coattails of the 953 in a bid to extract a huge amount of cash from Porsche enthusiasts. After all, though the new car is based on the 992 Carrera 4 GTS, only 2,500 examples of the Dakar will be manufactured. Want one? The starting price is a gob-smacking £173,000, which doesn’t include the Roughroads livery seen here. Then again, corporate branding legalities aside, we can’t imagine any of today’s car makers would want to slap the name of a cigarette brand on one of their products.

“The 911 is the only car you can drive from an African safari to Le Mans, then to the theatre and onto the streets of New York.” So said Ferry Porsche. This was, of course, only true if you owned a competition version of his company’s flagship. Even so, it’s clear Porsche intended for the 992 Dakar to live up to Ferry’s bold claim.

Before the car was unveiled in full last year, we were told about a torturous endurance test schedule subjected to a series of prototypes. The work included three hundred thousand miles of driving. Of these, six thousand miles were off-road. Cold-weather testing was carried out on the snow and ice of Sweden, heat testing was conducted in Morocco and, impressively, Porsche’s engineers managed to convince their bosses the car needed to be blasted up fifty-metre-tall sand dunes in the United Arab Emirates.

This is all very well, but what about real-world time behind the wheel? Instagram-friendly first drives for the world’s motoring media took place in far-flung locations, but 911 & Porsche World had other ideas. You see, we wanted to find out what the 992 Dakar is like to drive on the public highway. We also wanted to test the model’s mettle in an off-road environment no ordinary 911 would survive in. Our only hope was that Porsche wouldn’t be upset at the mess we’d be making.

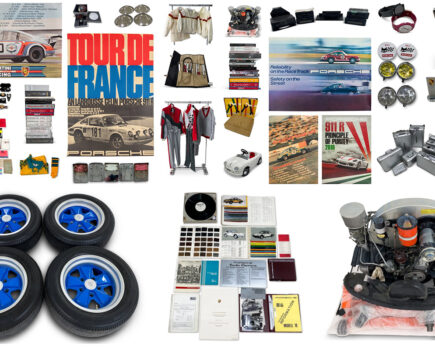

Our test car was presented in pristine cosmetic condition, freshly washed and resplendent in Roughroads livery, consisting of two-tone paintwork and a model-specific decal set. As mentioned earlier, this isn’t included at the entry-level price point, but can be yours as part of the £21,198 Rallye Design Package, which also delivers model-specific white alloy wheels, a Roughroads puddle light, GT sports steering wheel, blue seatbelts and various other interior tweaks, including Race-Tex fabric for the dashboard. For a further £2,846, the Rallye Sport Package comes with six-point harnesses, a fire extinguisher and a bolt-in roll cage.

If you’re not willing to shell out more than twenty grand, there are three rather more affordable (but still expensive) wraps to choose from, each inspired by the look of the 911s fielded in the 1971, 1974 and 1978 editions of the East African Safari Rally. Budget between £3,387 and £4,839.

You may have seen images showing suitably adventure-focused equipment on the roof of the 992 Dakar. Water and fuel canisters, recovery boards and even Porsche-branded spades are available to order. Main dealers will happily sell you these items from the manufacturer’s Tequipment accessories catalogue. There’s also a storage-friendly roof basket with auxiliary headlights, which plug into an external twelve-volt power socket. None of this is cheap, but at least you’ll have somewhere to keep your Porsche-branded tent.

A statement of intent is the appointment of special Pirelli Scorpion all-terrain tyres. These follow a chunky two-carcass design with a minimum tread depth of nine millimetres and strong resistance to damage. Wrapped around the Dakar’s nineteen-inch (front) and twenty-inch (rear) five-spokes, they’re no noisier on the road than winter tyres, though Porsche will allow buyers to order regular summer or winter rubber, should they prefer to do so. We reckon the car will look rather odd with those on.

Irrespective of the paint colour or body graphics you choose, there are plenty of external differences to set the Dakar apart from less adventurous 992s. The ride height is probably the first thing you’ll notice. In comparison to the current Carrera 4 GTS (which is twenty millimetres lower than a standard Carrera) on which the Dakar is based, the latter sits sixty millimetres higher by default, but can be raised a further thirty millimetres.

Even when lifted to this height, the car can operate comfortably at speeds of up to 106mph. The extra push is achieved by way of the same nose-end lift system available on other new 911s, though with hydraulic pressure increased and lifting also taking place at the rear.

Attention is unavoidably drawn to the substantial tow eyes. They’re permanent fixtures, forged from aluminium and powdercoated bright red, giving the Dakar the look of a competition car. There’s also underbody protection front and rear, stainless steel side skirts and subtle black wheel arch extensions, giving this 911 a stance all of its own in the 992 range.

It looks purposeful, that’s for sure. Not so easy to spot is the lightweight glass and use of carbon-fibre reinforced plastic (CFRP) for the rear spoiler and bonnet. We’ll come to the weight of the car after we’ve described the interior.

This is the first 911 I’ve driven where I’ve had to avoid mud on the door sills when entering the cabin. That said, the raised ride height makes the car easier to climb into than any other 911. The interior looks far more like that of the 992 GT3 than I was expecting. This is mostly due to the inclusion of CFRP buckets. Our test car features the aforementioned the Rallye Design Package, which means the seat backs are painted blue, while the door handles and various trim strips are finished in white. As standard, they’re all Shade Green Metallic.

A plaque highlighting the host Dakar’s unique build number is found on the dashboard. There’s a top-centre stripe on the steering wheel in all versions of the car, which also features customised graphics for the digital instruments. Oh, and there are no rear seats, even if you’ve declined the offer of a roll cage. This, so we’re told, is to save weight. To this end, a lightweight battery is in use. And, despite the addition of ride height adjustment hardware, big tyres and various chassis changes, the 992 Dakar is only ten kilograms heavier than the Carrera 4 GTS it’s based on — tipping scales at 1,605kg is a remarkable achievement, all things considered.

Although it feels like you’re in a new GT3, the Dakar is powered by the GTS’s twin-turbocharged three-litre flat-six, which kicks into life loudly when you twist the starter. The engine produces 473bhp and a considerable 420lb-ft torque. It might not have the top-end power of the GT3, but the Dakar’s wide spread of torque is better suited to the model’s off-road remit. Peak power is available all the way from 2,300rpm to 5,000rpm — arguably, there’s little need to rush up and down the eight-speed PDK gearbox, although you’d be denying yourself the aural pleasure resulting from such behaviour. Just make sure you have the sports exhaust activated at all times.

Remarkably, the only change to the powertrain is more robust air filtration. There have also been tweaks to the cooling system, but this was as much to compensate for the deletion of the central front radiator as it was for reliability in toasty temperatures — removing the middle heat exchanger resulted in an increase in the possible approach angle.

Heading out on the road, we don’t expect to take advantage of this benefit, but within seconds, it’s clear the Dakar feels very different to other 992s. As you’d expect, it presents typically sublime steering, a perfectly modulated brake pedal and distinctive boxer bark, but I’m acutely aware of how much higher I am sitting. The way the suspension moves is very different, too. Along with the ride height changes, the struts themselves are longer, allowing for more suspension travel. This is coupled with reduced spring rates, new steering tuning and special tweaking of the software controlling Porsche Active Suspension Management (PASM), Porsche Dynamic Chassis Control (PDCC), Porsche Traction Management (PTM), Porsche Torque Vectoring Plus (PTV+) and Porsche Stability Management (PSM). Essentially, each system has been updated to increase its capabilities in low-grip conditions.

In default Normal driving mode, the Dakar feels taut on asphalt, but with a lolloping gait you’ll not find anywhere else in the current 911 line-up. There is a little extra movement detectable at the rear after a large bump or rise in road surface, but this 992 still feels utterly controlled. Sport mode results in very firm damping and, in truth, discomfort on the poorly-surfaced B-roads I tackled.

Nonetheless, in this environment, on a nasty, wet and cold spring day, the Dakar feels pretty invincible. When a tractor came hurtling down the opposite carriageway, for example, I didn’t need to think twice about mounting a high verge in order to make way. Without wincing, try doing the same in any other new 911.

But wait! This Porsche is made for much more than a wet road and the occasional fight with an agricultural vehicle. To allow us to fully experience what the Dakar can do, we’ve taken up residence at a Ministry of Defence off-road testing facility, where several acres of sparse forest cover mildly undulating terrain layered in a combination of thick, gloopy mud and deep, soft sand, interspersed with lots of menacingly dark puddles (some of you might think of them as lakes). Not exactly prime 911 territory, is it?

Time to explore Rallye and Offroad, the Dakar’s new driving modes, selected using the rotary control fixed to the steering wheel. The Offroad setting is designed to keep the car moving through difficult terrain. It raises the suspension to its highest level and tweaks the all-wheel drive system for maximum traction. With disbelief, I hare around the facility seeking ever-harder challenges for the Dakar to tackle.

Earlier, I took to a soft piece of ground too slowly and the car ran out of ground clearance, bottoming out. This allowed the wheels to spin on the soft material underneath. The Dakar was beached. Life lesson: go faster.

With the assistance of a charitable support crew, the car was dragged out of sticky mud. The experience served to demonstrate how the Dakar is built not just for going where no other 911 dares to tread, but to do so at speed. The fact its 3.4-second sprint from rest to 62mph is a tenth of a second slower than it takes the Carrera 4 GTS to achieve the same is irrelevant, as is the observation top speed of 149mph makes this the slowest 992 currently on offer. Ultimately, the Dakar is the only new 911 capable of deploying such performance in inclement conditions. The way this 911 finds traction and keeps accelerating is mesmerising. Through it all, the 911’s usual driving characteristics shine through. Make no mistake, this Porsche is a huge amount of fun.

The icing on the cake, especially with such a fantastic playground to explore, is the Rallye driving mode. It’s similar to the Offroad setting, but with a lower ride height and more power sent to the rear wheels at all times. It’s more about playing with the terrain — as opposed to trying to get across it — and is especially enjoyable when traction control is disabled. Cue lots of big, silly, juvenile power slides and doughnuts in the mud. I think the Roughroads livery looks all the better for my efforts.

Despite the temptation many buyers will have to squirrel away their purchase as an investment piece, we hope the majority of 992 Dakar owners get a chance to experience everything the model is capable of, traits which justify the evocative name and equally thought-provoking colour scheme. This special 911 certainly lives up to both.