The original Aston Martin V8 engine was forged in endurance racing but also powered its world-class luxury sports cars. Here’s the story

Words: Jon Burgess Images: Paul Walton, Aston Martin, Max Earey, Iconic Auctioneers, Classic Motor Cars

As the 1970s loomed, Aston Martin was all too aware that its rivals, domestic and foreign, were moving away from straight-six engines. Buyers were demanding more performance from their GT cars – and the firm’s existing six, now at 4.0-litres for the DB5, had been taken as far as it could go before it became unreliable. Although DBR2s with 4162cc derivatives of the Tadek Marek-designed six had gone the distance, its main bearing caps proved weak in sustained testing. Something had to be done.

Chief engineer Tadek Marek was tasked with bringing the new engine to life: calculations suggested that a V8 would be the ideal compromise between the smoothness of a straight-six and the outright complexity of a V12.

Marek began work in 1963 and had a running prototype 4.8-litre prototype two years later, known as DP218. Extensive testing in modified DB5s showed some oil starvation, but it was nothing compared to what happened in competition. Racing driver John Surtees, 1966 World Sports Car Championship winner, wanted a Lola-Aston Martin to take the fight back to the Americans; that year, he had taken pole in a T70 powered by a 5.9-litre Chevrolet V8.

One such engine was taken back to Newport Pagnell and examined; retaining the 83mm stroke of Marek’s V8, Aston’s engine was bored out to 97.5mm. Extensive tests resumed, using a modified DB4 as a base: eventually, using quadruple Weber 45 DCOE carburettors, the smaller, lighter, 5.0-litre (4983cc) Aston engine made peak figures of 421bhp and 386lb ft torque in comparison to the 5.9-litre Chevy’s 412bhp and 398lb ft. Marek was not at all keen on seeing his engine race and petitioned against it – but race team manager John Wyer, keen to have a V8 to campaign, pushed forward, encouraging Aston Martin owner David Brown to have the engine completed to competition standard.

While Lola’s T70 MKIII, launched at the 1967 Racing Car Show at Olympia, would be sent to customers with a Chevrolet V8, two Lola factory cars, otherwise known as Lola-Aston Martins, would compete that season with the new engine from Newport Pagnell. Work to further distance the British V8 from its Chevy competitor resulted in another overbore, to 5064cc: peak figures of 450bhp and 413lb ft were recorded before they were sent to Lola’s Cambridgeshire headquarters. Testing had resulted in broken connecting rods and underperforming oilways, but these had been ironed out before Lola received its engines.

An Aston Martin DB5 modified as a development mule for the firm’s first V8 engine

Wyer was right to put Marek’s V8s through a racing programme; barely a season of thrashing – sometimes through trial and error – quickly revealed faults that would have taken years to iron out on a road car testing rig.

1967’s practice at Le Mans led to both cars overheating, which prompted machined, adjustable Cooper seal rings to be fitted to the blocks to help preserve the head gaskets, though poor airflow around the rear of the car had also pushed the cooling system too hard. While one car driven by Surtees and David Hobbs, retired with a holed piston, the other, driven by Chris Irwin and Peter de Klerk, had its fuel injection pump fail owing to a broken camshaft drive.

Earlier iterations of road tuned V8s had begun to crack around their main bearing housings – and while larger, stronger bearing caps were thought to have solved the problem, a post Le Mans shakedown of Surtees’ engine demonstrated that the issue remained, even in the overbored, harder worked race engines. A modified bottom end, with extensive webbing and buttressing, finally passed a 25-hour torture test on the dyno.

While these modifications were being carried out, Aston’s new car, the DBS, launched with the outgoing 4.0-litre Marek six in 1967 as compromise. Alan Crouch, later of Ricardo, added stiffening ribs, strengthened the main bearing housing and added longer cylinder head bolts, all the while increasing capacity to 5.34-litres (5340cc). The work took almost two years; the 345bhp DBS V8 which resulted, complete with Bosch fuel injection, looked outwardly similar to the DBS.

DBS V8 production didn’t last long before new nomenclature arrived in 1972; goodbye DBS V8 (and chairman David Brown), hello AM V8 saloon. By the time Series 3 production had begun in August, a quartet of Webers had replaced the Bosch fuel injection. As the factory thrashed long nights to make the V8 reliable, privateers honed the V8 for racing.

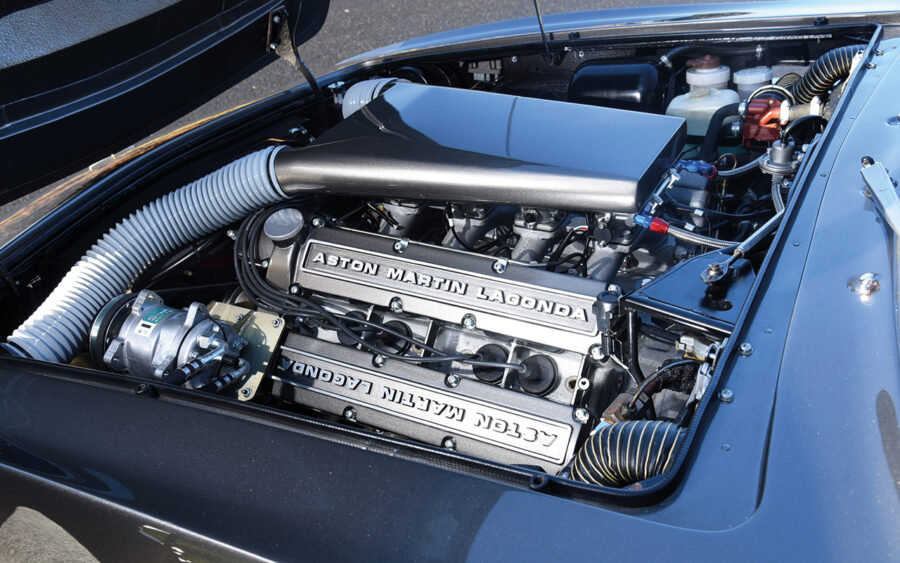

The Aston Martin ‘Marek’ V8 in situ in the DB5’s tight engine bay

Aston Martin had retired its works team from racing in 1964, supplying engines to Lola but otherwise staying well clear of motorsport. By 1973, however, privateers were looking to take the marque into serious competition again; while early DBS V8s had turned their wheels in anger at a limited number of Aston Martin Owners’ Club (AMOC) track days, Derbyshire-based Aston Martin dealer, Robin Hamilton, homologated a DBS V8 into a Group 5 racing car.

Meanwhile, AMOC member John Pope was building a wild Aston V8-engined Vauxhall Magnum to compete in the anything-goes Super Saloon category, using the running gear of a crashed fuel-injected DBS V8 in the Vauxhall’s shell. Looking for an outright win, Pope sought to up the power by using a pair of turbochargers; he was the first person to boost a Marek V8 in this way. An early tune of the engine, with two Garrett TO4s, managed 600bhp; when a pair of intercoolers were added, 700bhp was the result. It retired from competition in the early Eighties with a tyre melting 800bhp on tap, owing to higher boost pressure and a set of higher compression pistons.

Robin Hamilton’s involvement in the Marek V8’s racing career was far from over; by 1977, his DBS V8, nicknamed ‘The Muncher’, finished 17th at Le Sarthe, Aston’s first appearance there in 13 years. A quartet of oil coolers and four 50 Weber IDAs saw the V8 make 520bhp; the front end of the car, updated with a single headlight nose, used a spaceframe.

By the end of the 1970s, the ‘Oscar India’ raft of mechanical and visual facelifts were coming in to provide a home for Aston’s V8; the 1972 retrograde fitment of carburettors had made it easier to build uprated Vantage engines from 1977. A year later, drophead Volante variants arrived and the radical, Williams Town-penned Lagonda V8 had finally gone on sale (1979). The latter four-door saloon had been announced three years earlier, plagued by electronic bugs; previous attempts to bring back the marque, based on the DBS V8 and AM V8 saloon, didn’t even break double figures.

1979 also saw the return of Robin Hamilton’s DBS V8 to Le Mans, this time with a pair of Garrett AiResearch turbochargers and low compression pistons, with as much as 800bhp on tap. The engine wasn’t giving trouble this time; the DBS V8 itself, known as RHAM/1, had received modified, lightened bodywork (later to inspire the one-of-a-kind, One-77 based Victor of 2020) – it was the rear suspension and brakes that gave trouble across the Silverstone 6 Hours endurance race, and a conrod failed during the Le Mans 24 Hours with Derek Bell behind the wheel. Further attempts to take the V8 racing, with varying degrees of success, were attempted by the likes of Dave Preece, David Ellis, and Ray Taft, the former’s mid-engined Gipfast Special an abortive attempt to compete in the World Sportscar Championship, the latter two close (and prolifically successful) rivals in Aston Martin Owners’ Club racing, with the Ellis V8 competitive well into the 1980s.

The short-lived Aston Martin DBS V8. This example is an ex-press car formerly owned by actor and comedian Steve Coogan (Image by Iconic Auctioneers)

Robin Hamilton’s RHAM/1 appeared one last time to set a caravan towing record in 1980 at Elvingdon Airfield in North Yorkshire, managing 152mph in torrential rain.

Although RHAM/1 was retired, Hamilton had not stood still; he had instead worked on a new Group C design to fight Porsche at Le Mans and elsewhere in endurance racing.

The new car had echoes of the earlier Lola-Aston Martins powered by Newport Pagnell; Lola designer Eric Broadley, of Mk6 and GT40 fame, penned the chassis. Hamilton hadn’t intended for his contender to use an Aston Martin engine, but following talks with Victor Gauntlett of Pace Petroleum, who headed the consortium of investors with a 10 per cent stake in Aston, the Marek V8 was headed back to Le Mans in a factory entry of sorts.

Turbocharging had finally reached Newport Pagnell’s road cars – at least in experimental form. The five-lamped, gull-winged, twin-turbocharged, stillborn Bulldog of 1980 remained a fascinating one-off – but it wasn’t the first time a Marek V8 had been mounted in the middle of a road car. Nine years previously, factionalism within the Brown family had killed off any chance of the Siva S530 making production. Chief engineer Mike Loasby, who had left for DeLorean the year previously, had wanted the Marek V8 in an exotic, mid-engined model with the goal of reaching 200mph.

Though the car never reached that speed in period, lessons learned from Bulldog fed into a twin-turbocharged Lagonda prototype, further broadening Aston’s experience with forced induction; alas, it went no further. For the time being, Aston’s V8 road cars would remain naturally aspirated. Supercharging would come in 1992 – but it wouldn’t be until 2016, when Gaydon’s all-new AE31 debuted in the DB11, that turbocharging would grace a production Aston.

Nimrod Racing Automobiles (NRA) was the formal result of talks between Hamilton, Gauntlett and Peter Livanos, one of the shareholders behind the Pace acquisition of Aston Martin in 1981; Pace’s stake in Aston was now upped to 50 per cent, (partner, CH Industrials, owned the other 50 per cent) and Gauntlett was now chairman; CH Industrials controlled Aston’s service and engineering group, Aston Martin Tickford.

The Aston Martin V8 picked up where the DBS V8 left off, initially retaining Bosch fuel injection. Weber carburetion followed (Image by Max Earey/Aston Martin)

NRA now had its ambitions firmly set on endurance racing – but it misread the Fédération Internationale du Sport Automobile’s (FISA’s) homologation rules for the upcoming season, meaning that the budget had to accommodate the development of two disparate chassis and bodies, one to meet the FISA rules (C2, World Endurance Championship), the other to meet those of the International Motor Sports Association (IMSA, GTP specification). Other cars were produced for a privateer team, Dawnay Racing, owned by Viscount Downe, John Dawnay, the AMOC president who wanted a car of his own when it was demonstrated at the Dubai Grand Prix in 1981.

Aston Martin Tickford handled the engine preparation for the Aston Martin Nimrods (named engine-first, as per FISA rules). Breakages were frequent, funds quickly ran dry and Robin Hamilton exited the World Endurance Championship to concentrate on IMSA entries in 1982, building its own engines from then on, owing to friction between NRA and Tickford, whose engined proved unreliable. The former firm was wound up the following year owing to crashes Stateside.

EMKA Racing looked after the European (FISA) entries from late 1982 until 1984 on a new chassis designed by Lola’s Len Bailey, with naturally aspirated Tickford V8 amidship. Struggles to find sponsorship and another arbitrary set of rule changes from FISA forced its withdrawal; Porsche’s factory team also boycotted the event in protest.

That left Dawnay Racing’s Nimrods to contest 1984’s 24 Hours, a quarter of a century after Aston Martin’s famous final victory at Le Sarthe. Unfortunately, both its cars, chassis 004 and 005, crashed in the race. 005 had used a troublesome twin-turbo development of the Marek V8 in practice; despite using a similar configuration honed on the Bulldog, it was underpowered. With a faster revving, naturally-aspirated qualifying engine fitted, 005 lay fifth in the race until 004, driven at the time by John Sheldon, flipped over the barriers following a 200mph blow-out on the Mulsanne Straight, throwing burning fuel and debris on to and around the track. Carnage ensued: not only was a marshal killed by a piece of flying suspension from 004, but 005, of Ray Mallock and Drake Olsen, hit the barriers with the Olsen at the wheel, as he swerved to avoid Jonathan Palmer’s Porsche, the car trailing Sheldon before his tyre let go.

No driver suffered long-term injuries in the aftermath but there were to be no quarter-century celebrations for Aston Martin at Le Mans. Towards the end of 1984, however, Swiss newcomer Chuck Graemiger’s Cheetah G604 combined the world’s first carbonfibre composite tub with a Tickford Marek V8.

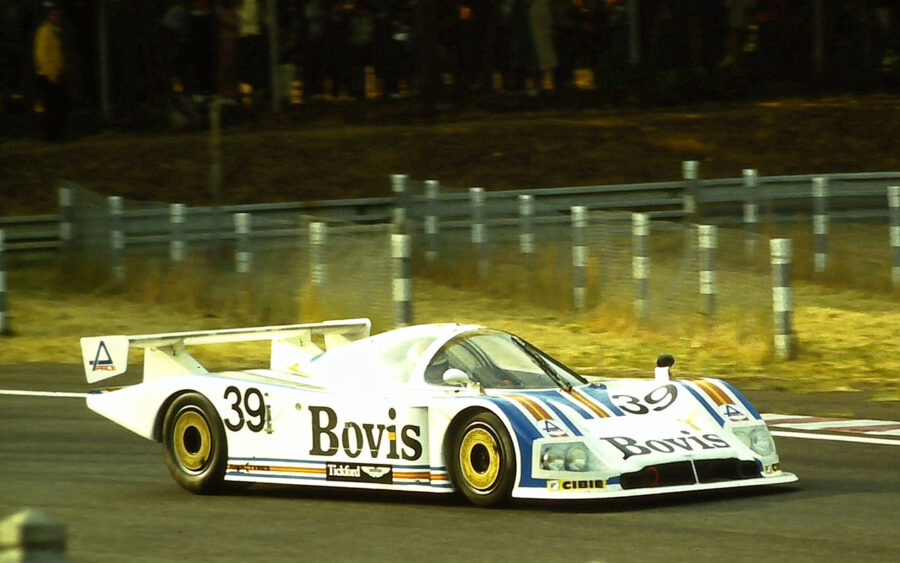

The Aston Martin Tickford Nimrod at Le Mans in 1982

Not that that stopped privateers from continuing to campaign the former EMKA Racing Aston-chassied cars into 1985 – but after that, Aston-powered cars at Le Mans were on hiatus, although Ray Mallock and Richard Williams continued to race a Nimrod C2 chassis with Ecurie Ecosse for the next few years.

1986 finally saw fuel-injection return for the Series 5 AM V8s, although the ‘X Pack’ power options retained carburettors. Radical work with the surgeon’s knife brought back a modern interpretation of the DB4 Zagato – the V8 Zagato. Shorter, lower, stiffer and far lighter than the V8 saloon, fewer than 100 were built over a four-year period.

By then the V8 saloons were showing their age, and it was decided that an entry level car would help secure Aston’s future. The V8 Zagato generated significant sums of money, which would help fund the new car’s development.

By the late 1980s, Ford had been found as Aston’s unlikely saviour. Former Ford of Britain head of public relations, Walter Hayes, knew both Henry Ford II and Victor Gauntlett personally; by 1987, the Blue Oval had a 25 per cent stake in the firm. Traditionalists baulked, fearing that Ford would reduce Aston Martin to a trim shop for its cars, much like the casual fate that befell Ghia.

During this time, Aston returned to Group C racing with a successor to the Nimrod, the AMR1, built and run between Newport Pagnell, Ecurie Ecosse, Proteus Technology (with Richard Williams) and race car builder Ray Mallock Limited.

‘X Pack’ power options for the AMV8 retained carburetion even when the range returned to fuel injection in 1986

For Aston’s new entry level road car, designers had been competing to design a successor to the glorious, but outmoded V8 saloons – from five competing teams, it was the quarter-scale model of John Hefferman and Ken Greenley, Royal College of Art tutors, that won.

Acutely aware of Aston’s shortage of funds, the successful proposal, Project 2034, used Audi 200 front headlights and VW Scirocco rear clusters, smoked as to hide their origin.

The 2+2 GT body style was retained, so as not to frighten off long-term customers; its engine had to meet forthcoming emissions standards, as well as run on unleaded petrol from 1992. Aston also wanted a simpler to build car – at the time, it was producing four to five cars a week. A five-speed ZF manual, and a three-speed automatic, were also selected as transmissions.

Project 2034’s requirements saw the 5.3-litre Marek V8 updated with dual-overhead cam heads and hydraulic valve lifters by Callaway Engineering in the US. Tickford had looked into 32 valve heads for racing as early as 1984, but the funding simply wasn’t available, nor did it get the job to transform the Marek V8 for the new decade. The new engine provided the basis for the AMR1’s racing unit; by 1989, four cars had been built, engines had gone from 6.0-litres to 6.3-litres, and one car, AMR1/01, managed 11th place at the Le Mans 24 Hours.

By 1990, Protech’s future was looking uncertain: FISA rules had changed once again, and for 1991, they required a naturally aspirated 3.5-litre engine. There was no money to take things further; the interim AMR2 for 1990 was abandoned, and Protech, the team that ran the AMR1 with Richard Williams at the helm, closed down.

Still, the Virage saloon was gradually improved. Aston Martin Works Service offered a 6.3-litre conversion at the end of the year; assisted by late marque specialist, RS Williams, the larger engine was based on the bored out and stroked version of the now-dead AMR1 racing car’s Marek V8. It remained naturally aspirated, Williams being an outspoken critic of turbocharging during the Nimrod years. He developed the engine further, and was working on a 7.0-litre, 500bhp version when Works Service bought the rights.

The Aston Martin V8 in 5.3-litre form under the bonnet of the Aston Martin Virage

Results were dramatic: the 6.3-litre conversion lifted power from 330bhp to 465bhp. Lower, wider, and dramatically styled to cope with the extra grunt, massive 14-inch brake discs, and a six-speed ZF S6-40, as used by the Lotus Carlton and Chevrolet Corvette ZR-1, replaced the ‘Friedrichshafen’ five-speed. If desired, the Works 6.3 engine could also be had in Volante form.

Suddenly, all eyes were back on the Virage; the 6.3 had proven enough of a spectacle for Aston to pursue extreme levels of performance. It was already working on a twin-supercharged car to revive the Vantage nameplate, having purchased several ‘blown’ Ford Thunderbird SCs to better understand Dearborn’s EEC IV engine management system.

Launched to huge critical acclaim in 1992, the Vantage had 550bhp on tap from its 5.3-litre V8 – and 550 lb/ft peak torque. A reduced compression ratio and the use of Ford’s EEC IV engine management – instead of the Virage’s Weber-Marelli unit – allowed the car to meet emissions regulations worldwide. Retaining the Virage’s roof and door skins, the Vantage was otherwise restyled by John Heffernan, with every other panel being new.

Aston Martin Works remained busy, adding a Virage Shooting Brake to the range and a built-to-order, four-door Lagonda Saloon by 1994, bringing back the Lagonda name for the sixth (and seventh) time. A handful of specially made, five door Lagonda Virage Shooting Brakes were also constructed for a private client.

As the 1990s wore on, however, the evocative V-car range was clearly on borrowed time. The DB7 had taken the Virage’s place as the entry level Aston; the brutish, Marek V8-engined cars, like the V8 saloons they succeeded, were outmoded.

The Aston Martin DB7 of 199x saw a return to six-cylinder (and eventually V12) power for the brand

It would be emissions laws, not Ford, that would mitigate the V8’s demise, however. The Blue Oval had full control of Aston by the end of 1992, but Aston ploughed on, giving the Virage the Vantage’s body but retaining its tamer mechanicals (and revised suspension) by 1996, naming it the V8 Coupé. The Volante carried on unaltered for another year until a lengthened model, the V8 Volante Long Wheelbase, adopted the V8 Coupé’s Vantage-lite styling cues, picked up the baton, produced in parallel until 2000.

Not that the Vantage (sometimes referred to retrospectively as the ‘V550’) was going to go out without a bang. More suck and squeeze, really, as from 1998, Works Service offered (and continued to offer) a ‘V600’ conversion for existing Vantages, which upped the already considerable power output to 600bhp and 600lb ft of torque.

A final batch of 40 Vantages, celebrating the four decades since Aston’s win at Le Mans, were announced in 1999; one made for each year since the firm’s victory at Le Sarthe, V8 Vantage Le Mans cars boasted 604bhp, 604lb/ft torque, and used special Dymag alloy wheels, Koni shocks and a twin-nostril, blanked-out grille. Buyers could also opt for the standard 550bhp/550lb ft ‘V550’ tune if they so chose.

In 2000, as EU emissions laws loomed large, Works Service completed nine final V8 Volante Vantage cars, allegedly building one to Volante Long Wheelbase specification.

As production of the Marek-engined road cars ceased, David Ellis (of DBS V8 AMOC racer fame) gave the engine one last hurrah; drawing on 34 years of racing experience, he designed his own front mid-mounted carbon fibre monocoque tub to take a 730bhp 32V Marek V8. The V8 GT700R was born, complete with carbon fibre bodywork resembling a stretched Vantage. It won numerous AMOC Super GT races in 2008 and 2009 with David behind the wheel; a fine tribute to Marek’s masterpiece, which carried Aston Martin into the new Millennium.

Aston Martin ‘Marek’ V8 timeline

1963

Chief engineer, Tadek Marek, begins work on a new V8.

1965

First 4.8-litre V8 prototypes completed.

1967

5.0-litre variants of V8 fitted to Lola T70 MkIII sports car prototypes. DBS launched with 4.0-litre straight six while Aston works to improve the V8 following breakages on track.

1969

DBS V8 announced; Sir David Brown has a one-off four door Lagonda DBS V8 produced for his personal use.

1970

5.34-litre, Bosch fuel-injected DBS V8 [Series 1] finally arrives after nearly three years of the stop-gap DBS. Far more powerful than the outgoing Marek six, it weighs just 30lb more fully dressed.

1971

US certification finally arrives for the DBS V8 in October, allowing cars to be sold there. Mid-engined Aston V8-powered Siva S530 mooted as a production car but remained a one-off.

1972

Series 1 V8 production ends in May, giving way to the AM V8 [Series 2]. Sir David Brown relinquishes control of Aston Martin to William Wilson’s Company Developments. Sotheby Special/Ogle Aston Martin revealed at Montreal, with special Triplex glass and a tail full of brake lights (showing stopping force). Two eventually built.

1973

AM V8 [Series 3] cars debut; Bosch fuel injection is replaced by four twin-choke Weber carburettors.

First twin turbo V8 built for Super Saloon championship by John Pope. Robin Hamilton begins work to homologate a DBS V8 for Group 5 racing.

1974

Four-door Aston Martin Lagonda V8 [Series 1] launched; seven are built, with production terminating two years later.

1975

A new consortium, Aston Martin Lagonda (1975), saves the firm from insolvency.

1976

‘Razor edge’ William Towns-styled Aston Martin V8 Lagonda [Series 2] debuts (below); sales don’t start until 1979, however.

1977

‘Britain’s first supercar,’ the V8 Vantage [Series 1], appears. Power is up to 390bhp; aerodynamic aids include a chin air dam and large rear spoiler.

Robin Hamilton’s DBS V8 finishes 17th at Le Mans.

1978

‘Oscar India’/’October Introduction’ [Series 4] AM V8s released, with a facelift and revised suspension to control rear-end lift at speed. V8 Vantage production continues, with cars facelifted to match. Drophead Volante [Series 1] launches.

1980

Gull-winged Bulldog supercar revealed with a mid-mounted Marek V8 a target speed of 200 mph. It remained a one-off, but still exists, having been restored by Classic Motor Cars (CMC) during lockdown. 10 per cent stake in Aston bought by Victor Gauntlett of Pace Petroleum, and a consortium of investors.

Aston Martin Bulldog following its restoration by Classic Motor Cars (Image by CMC)

1981

Victor Gauntlett, of Pace Petroleum, becomes Aston’s new chairman.

Nimrod Racing Automobiles, a joint venture between Aston and Robin Hamilton to race in Group C, is formed.

Aston Martin Tickford created.

1982-1985

Nimrod chassis compete with varying degrees of success, between NRA, EMKA Racing, and Dawnay Racing. Two Nimrods, entered privately, crash and are nearly destroyed (but later rebuilt) during the 1984 Le Mans 24 Hours. EMKA Astons, and carbon fibre monoque tubbed Cheetah Astons, compete until 1985.

1986

AM V8 [Series 5] cars now launched, with Weber-Marelli fuel injection and BBS wheels. Volante [‘Series 2’] finally updated with Oscar India styling package and body-kitted Volante Vantage [‘Series 3’] no available. Lagonda V8 [Series 3] arrives. Extensive changes to electronics, styling mostly unaltered. V8 Vantage [Series 2] arrives at the same time, with further ‘X Pack’ upgrades available. Spiritual successor to the DB4 Zagato, the V8 Zagato, shown at the Geneva Motor Show, available in coupe and Volante drophead body styles.

Heffernan and Greenley, RCA tutors, beat four other design teams, winning the race to design Aston’s new V8 saloon successor. Project 2034 is born; adopting a shortened, heavily modified 1974 Aston Martin Lagonda chassis and platform.

1987

Ford buys a 25 per cent equity stake in Aston Martin from the Livanos/Gauntlett consortium, brokered by middle-man, Walter Hayes.

AMR1, the successor to the Nimrod, is launched, run by Protech Engineering with Richard Williams as manager, with a 6.0-litre variant of the upcoming Virage’s 32v V8.

1988

Virage saloon launched, with Callaway-enhanced, dual overhead cam, 5.3-litre V8. Five-speed manual, and three-speed automatics, offered.

1989

Aston Martin Lagonda [Series 5] production ends. Ford buys Jaguar (and Aston Martin, outright).

AMR1, now a 6.3-litre manages an 11th at Le Mans.

1989 Aston Martin AMR1 (Image by Iconic Auctioneers)

1990

Virage Volante launched.

Protech Engineering closes owing to a lack of funds needed to develop a 1991-season compliant 3.5-litre race engine.

Aston Martin Tickford sold off by controlling owners, but bought back by its management.

1991-1992

High-performance, wide-bodied Works Service Virage/Volante 6.3 conversion offered (below). Twin-supercharged Vantage arrives. Incumbent chairman, Victor Gauntlett, steps down; caretaker, Walter Hayes, steps in. Ford takes full executive control of Aston Martin. Works offer Virage Shooting Brake.

Aston Martin VIrage 6.3 Works (Image by Max Earey/Aston Martin)

1994

Hayes steps down; DB7 production begins in Bloxham, Oxfordshire.

Lagonda Virage Four Door and Lagonda Virage Five Door Shooting Brakes revive Lagonda name; built in tiny numbers.

1996

V8 Coupé arrives, replacing Virage saloon; essentially a Virage with a Vantage body.

1998

Works Service offer V600 conversion for existing Vantages; power and torque upped from 550bhp/550lb/ft to 600bhp/600lb/ft. Works Service carry on converting Vantages after production is wound down.

1999

Commemorative V8 Vantage Le Mans announced; 40 final cars with 604bhp, uprated suspension and twin-nostril grilles.

2000

V8 Coupé and Volante/Volante Long Wheelbase production ends; nine Virage Volantes commissioned and built by Works Service