The A-Class was supposed to be Mercedes’ most innovative car ever but turned into a PR disaster. Today its a real modern classic

Words: Craig Cheetham Images: Mercedes-Benz

The original ‘baby’ Benz, the A-Class, comes of age this year, marking 21 years since its debut and 20 since it went on sale in the UK.

Codenamed W168, it had a difficult launch. After being brilliantly well-received by the world’s motoring media on the press reveal, it fell, quite literally, at the first hurdle.

Swedish magazine Teknikens Varld subjected all of its road test cars to what it called the ‘Elk Test’, simulating an evasive manoeuvre to swerve around a moose that idly sauntered onto the carriageway. Granted, this is hardly likely to happen on a quick nip down to Waitrose for a bag of quinoa, but nevertheless it caused a storm of bad publicity, making the national TV news in Sweden, Germany and the UK, and leading to a host of other European motoring magazines replicating the Elk Test to see if they, too, could get an A-Class to turn turtle by swerving from side-to-side at 40mph.

The answer, in most cases, was ‘yes, they could’, and Mercedes-Benz had a major PR disaster on its hands.

Indeed, what followed was a masterclass in bad publicity and good public relations, which, to this day, is used to educate PR students about the importance of humility, honesty and corporate integrity in the face of a serious, brand-damaging crisis. It’s the perfect example of holding up your hands and admitting you were wrong, and given that Mercedes has sold more cars in the first half of 2018 than ever in its history, the brand has clearly come out the other side…

The man challenged with putting it right was Juergen Hubbert, the then CEO of Daimler, who retired in 2005.

He said: “There was nothing comparable at the time. This was the biggest disaster to hit Mercedes-Benz.

“We had our own tests, of course. Some very demanding ones. But not the moose test. This was unique – an extreme slalom at high speed, which would upset the balance of any car. But that is not an excuse and not one we used. Other cars did not fall over, ours did, and it was a sub-optimal combination of centre of gravity and chassis adjustment that were the problem.”

Hubbert found out about the rollover whilst at a major press event in Tokyo, where Mercedes was in the process of launching the Maybach brand. There and then, he made the necessary call to ensure that the A-Class production lines were stopped and no more cars delivered to customers. He then arranged for the 2,500 cars that were already with customers to be immediately recalled.

In the face of a crisis, it was the only responsible thing to do, and despite the criticism faced by the car, Hubbert was praised for his immediate actions – despite the high profile of the Elk test failure, not one individual was ever injured as a result of the car’s top-heavy handling.

The next move came while sitting on the floor of a Boeing 747 between Tokyo and Stuttgart, as there were no seats left and Hubbert wasn’t prepared to wait for a later flight to get him and his senior team back to head office.

“Our reputation meant everything, so we sat on the floor of the plane and discussed what we could do, to discover the cause, to fix it and to communicate the solution.”

Whilst airborne, Hubbert had arranged for a conference room next to his office to be turned into a crisis hub, where he would meet with engineers, press office staff and marketing teams, as well as those from official bodies that were investigating the rollover. There were, he admitted, many sleepless nights.

“Too many things are going through your head. One is the technical solution. Another is the image of the brand. The third is your family. You have to prepare your family for the potential end to your career, with all the associated consequences.”

After negotiations with Bosch, which supplied the technology to higher spec A-Classes, Hubbert, demanded that all W168s be fitted with an Electronic Stability Programme (ESP) as standard, and immediately demonstrated the technology on a media event in which journalists were invited to replicate the Elk Test conditions. With ESP, there wasn’t a single drama.

“It was essential to rebuild the damage we’d done to our brand,” he said. The A-Class subsequently became the first compact car to be fitted with ESP across the range, and a benchmark for small car road safety. ESP is now fitted as a mandatory requirement to all new cars sold in Europe, so in many ways the rollover disaster made its own contribution to road safety.

Unsurprisingly, the W168 got off to a slow start in the showrooms, with customers acting warily following the global media exposure of the Elk Test fail, but as buyer confidence returned the A-Class evolved to become one of the brand’s best-sellers, even spawning a long-wheelbase variant and a high-performance A210 AMG model before it ceased production, replaced by the W169 A-Class in 2005.

Over half a million A-Classes were sold between 1998 and 2005, and ironically the car that failed the Elk Test was – in its own way – responsible for one of the most significant advances in road safety – ESP.

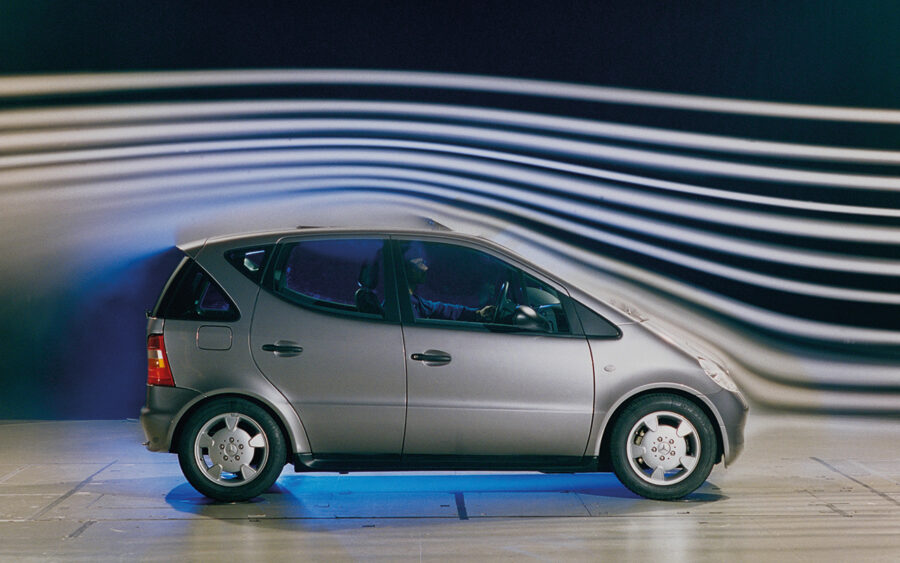

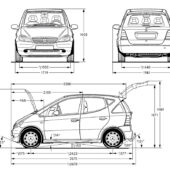

It was otherwise an extremely clever design, evolved from the layout of the ‘Smart’ city car to replicate some of its space-saving features. Chief among them was its clever ‘Sandwich Floor’ with the gearbox mounted below the passenger compartment in order to free up passenger space. It was billed as being the size of a supermini, but with the passenger space of a large car, though it’s fair to say that the structure did, ultimately, lend itself to the A-Class being a bit top-heavy.

It had some interesting styling features, though. The one-piece ‘floating’ dashboard being one, and the wraparound rear window being another, giving the A-Class far better rear visibility than most of its rivals.

Like all mainstream Mercedes models of the era, the interior felt high class and well screwed together, and the powertrain was adequately lively without threatening to set the world on fire.

Pick of the range was the A170 CDi, which offered 65mpg diesel economy and a decent turn of pace, though for purists it’s the A140 entry-level car that’s the closest to the original design concept. Thanks to the extra cost of adding ESP, it’s also a variant that never made the company a profit…

Time has also thrown up another less appealing Mercedes trait of the era, too, with A-Classes having quite a propensity to rust. They’re not as bad as the C-Class and E-Class models of the era, but they’re not great, with frilly wheelarches, front and rear valances and subframes being particularly vulnerable to corrosion.

As a result, many have already been scrapped, while many of those that remain are clinging onto life as cheap, disposable bangers that are slightly classier than a Vauxhall Astra or Toyota Corolla (both of which are significantly more rot-proof, alas…)

But, as with all cars as they get older, it won’t be long before numbers are depleted to a level where classic interest takes a hold. And there’s no denying that the A-Class was a very significant car of its era, for reasons both right and wrong.