The original Virage from 1988 has never gained the popularity of the earlier DB and V8 models despite being Aston Martin’s last genuinely hand-crafted car. We try an early example

Words and images: Paul Walton

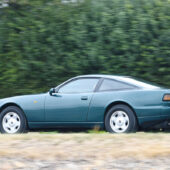

“That’s very pretty,” said a random stranger as he walked past the green car seen here. “What is it?” These few words perfectly sum up how the majority view the Aston Martin Virage. Despite coming from one of the world’s most famous automobile manufacturers with a lineage that’s second to none, the car isn’t as widely recognised as other members of its immediate family.Yet in my opinion, the Virage is Aston’s most distinctive model from the last 40 years with a fascinating and unique history.

By the mid-80s, Aston Martin was in desperate need of a new car. Although still pretty, the existing V8 range was simply a facelift of the DBS from 1967 and although it had received several updates throughout the Seventies – including the introduction of the fast Vantage model in 1977 – it was clearly outclassed compared to newer rivals such as the BMW 6-Series, Ferrari Mondial and the Porsche 928. As a result, production had reduced to a dribble which, considering the Newport Pagnell factory made just four cars a week (the same time it took Ferrari to make 50), was a real worry for Victor Gauntlett who had taken over as chairman in 1981.

And so, in 1986, he instigated a replacement that would take the company into the next decade. Internally designated DP 2034, as a front-engined, rear-wheel-drive coupe, the new car wouldn’t break any new ground while the interior would feature the kind of luxury Aston’s customers had grown to expect. It would also use the company’s trusty Tadek Marek-designed 5.3-litre V8 but it would need to be compatible with lead-free petrol and able to meet UK and American emission laws yet without losing performance.

To achieve this, it was clear that four valves per cylinder was the obvious route. After looking at the cost and the development time, the job of developing the engine was awarded to Callaway Engineering based in Connecticut in the US. Work started on the four-valve conversion in April 1986, finishing 18 months later. The power of the modified engine was quoted at 326bhp with 365 lb ft of torque compared to 305bhp/340 lb ft of the Series V V8 saloon.

“The goal for the production engine,” explained Reeves Callaway in Paul Chudecki’s 1990 book, Aston Martin and Lagonda Volume 2: V8 models from 1970, “was to design, execute and prove the initial durability of the four-valve configuration and there, essentially, our responsibility ended. Aston’s responsibility then started with the finalising for production of all the ancillaries and, most importantly, all the engine management system to comply with the required standards.”

There were also revisions to the cooling system and a new engine management system was devised using Weber-Marelli electronic fuel injection. A new intake manifold design was also developed.

Gauntlett originally wanted the car to have a new chassis but due to needing to rationalise components to increase production, a shortened Lagonda steel platform was used instead.

In May 1986, Aston’s chairman approached five design studios to submit a design for the car including William Towns who had been responsible for the original DBS and Lagonda saloon. He gave them just four months until August to produce a quarter-scale model of their ideas.

The designs were then put on display in the Service Department at Newport Pagnell and a mixed jury of executives, dealers, customers and others were asked to vote for their favourite. In October, the contract was eventually awarded to two Royal College of Art tutors, John Heffernan and Ken Greenley, who had previously designed the Panther Solo and the Bentley Continental R.

Said Heffernan during a 2018 interview, “Victor Gauntlett phoned Ken and said ‘Right, you’ve done a Panther, you’ve done a Bentley – you’re probably about right for us now.’ Very laconic, was Victor. The brief was to replace Bill Towns’ DBS, which I’d always liked a lot, but it had stopped selling.” Heffernan went on to say the shortened Lagonda chassis had a huge impact on the design, since the retention of its boxy bumper infrastructure dictated a less rounded platform than he originally desired.

To save time, the design went from quarter-scale to full-size model in one hit although there was extensive small-scale testing in Southampton University’s wind tunnel. This soon showed the tail needed to be higher to negate rear lift. The original design also featured pop-up headlights, but due to Aston’s previously poor experience with these on the Lagonda saloon they were soon substituted for fixed headlights, sourced from the Audi 200 saloon. The rear light clusters were VW Scirocco while the indicators were Porsche 928. The body was made from hand-formed aluminium panels, while suspension was via all new double wishbones at the front and a cast aluminium De Dion rear axle located by triangulated radius rods and a Watts linkage. Bilstein dampers were developed especially for the car.

By being longer, wider and having much crisper, angular lines, the new model was very different from the outgoing V8. Yet neither did it push the boundaries of car design and, thanks to the famous grille and overall proportions, was still clearly an Aston Martin.

“It was important that, although new in virtually every way, the Virage was of evolutionary rather than revolutionary design,” said Gauntlett in the January 1989 issue of Road & Track. “It has to be a car that could stand in line with every post-war Aston Martin and be the self-evident successor to that tradition.”

Continued Heffernan in 2018, “It was meant to be a conservative car; it wasn’t sensational. A lot of the English magazines were critical of Aston building a front-engined car when the Italians had gone mid-engined. Now 30 years later, Ferrari is still coming out with lovely front-engined designs.”

For the name, Victor Gauntlett wanted one that started with a V to match Vantage and Volante, finally deciding Virage from the French for curve. The car debuted at the 1988 British Motor Show at the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham; the show’s visitors were clearly impressed by the new car, since by the end of it, 144 customers had ordered one, paying a £20k deposit to do so.

“I am very proud that the job of unveiling this new car has fallen to me,” said a beaming Gauntlett to the assembled crowd. “We have a vision that the best days of Aston are yet to come. The Virage is a car worthy of a great past and an exciting future.”

Aston was also proud it had two examples of the Virage on its show stand, one silver and the other in metallic green. “If you’ve only got one, it’s a show car,” said the car’s co-designer, Ken Greenley, to Autocar magazine for its October 26, 1988 issue. “Two cars give you credibility – there’s a production line at work.” This was overly confident, though, since the cars on display were two of the five prototypes that Aston Martin’s engineers had produced since April 1987 to develop the Virage. Due to several last minute issues, the first production examples weren’t delivered to their owners until January 1990.

With the Virage’s debut coming a year after Ford had taken a major stake in the company, Gauntlett had acknowledged the American giant’s hands-off approach during the latter stages of the car’s development.

“We wanted to give for money to Ford who had been as good as their word, with no nasty thoughts about badge engineering. And I think it’s important to mention Ford. I want them to see the Aston and think jolly good show.” Ford obviously did, since it bought the company outright five years later.

When journalists finally got to drive the car 18 months later, they too were impressed by the Virage. “The new car outperforms the old in every respect,” said Sports Car International in its September 1990 issue. “Its quicker, sharper handling, more refined and has an astonishingly good ride. It’s better made too. The factory’s craftmanship is legendary but now it’s allied to Nineties standards of quality and reliability.”

Impressive words – but they needed to be, since initially at £120,000 in the UK (later increasing to £135k), the Virage was more expensive than the Bentley Turbo R, Ferrari Testarossa and Lamborghini Countach. Unsurprisingly, the car was never a huge seller and just 411 coupes (which include 80 examples of the Vantage 6.3 from 1993) and 233 Volantes (which had arrived in 1992) were produced, before the car was replaced by the slightly updated but otherwise identical V8 Coupe in 1996.

It’s because of these low numbers plus the introduction of the DB7 in 1994 that the Virage has always been overlooked. Not only at £80k was the newer car more affordable and therefore produced in greater numbers (around 7,000), but it featured the sort of smooth, curvaceous lines that were more in keeping with the brand. It might have started life as a Jaguar project [see AMD issue 4, p32] and lacked the handcrafted appeal of its larger sibling but it arguably looked more of an Aston than the Virage.

But over four decades since the car’s debut, is that still the case? Or should the Virage finally be appreciated for the proper, big-engined Aston it always has been?

Aston Martin Virage 5.3 on the road

This Balmoral Green example I’ve arranged to drive to try and prove this is a perfect example of the breed. Registered in January 1990, it’s one of the earliest produced yet remains immaculate.

The sharper, crisper, more angular lines might be very different from every Aston that came before or after it, but, together with Virage’s sizeable dimensions, they result in a big, bold and imposing car. As Performance Car magazine said in its April 1990 issue, “It really does look sensational in the flesh: big and solid looking, ultra-smooth and finely integrated.”

Yet there are similarities with Aston’s older models that go beyond the familiar shape of the grille if you look for them. Take the rear window for example; the way it tapers towards the bootlid becoming much narrower than the wings reminds me of the DB4 Series V that I tested in the previous issue (p66).

Unlike Aston’s later cars that were mass produced at the current Gaydon factory, the Virage was one of the last to be handmade at Newport Pagnell. As a result, the shut lines are inch perfect and when I climb inside, the door shuts with a solid, mechanical click.

And although the flat-fronted dashboard is surprisingly simple, featuring ordinary-looking plastic switchgear sourced from a manufacturer of lesser cars, the interior still has all the luxury of an exclusive gentleman’s club. The soft Connolly leather has been perfectly handstitched while the yards of thick walnut veneer across the fascia make it look and feel like a piece of Queen Anne furniture.

Due to the car’s dimensions, there’s plenty of interior room allowing for large, armchair-like seats, plus when owner James Richardson gets in beside me there’s so much space between us you could park a Mini in the gap.

According to a small brass plaque on one of the cam covers, the V8 was built by Aston employee Mike Peach. Not something you’d get from a mass-produced Jaguar or Porsche, it further adds to the car’s image of being a low-volume, handmade sports car.

When I turn the key in the ignition, the 5.3-litre erupts immediately into life with a baritone yet not overly obtrusive gravelly note. This example has a ZF five-speed manual gearbox that was fitted to around 40 percent of the cars produced, the majority having Chrysler’s four-speed TorqueFlite transmission, which was replaced with a four-speed unit in 1993.

Despite the car’s hairy-chested, masculine image, I’m surprised by both how light the clutch is and how the gearlever guides smoothly into first. With an empty road ahead, I give the throttle pedal a proper shove resulting in a sudden and hard surge of power, the free-revving V8 needing little persuasion to deliver its 326bhp. Although the 0-60mph time of six seconds is slow by today’s supercars – no doubt partially caused by the car weighing a hefty 1,973kg (4,349lb), around 238kg (525lb) more than a Jaguar XJ-S V12 – the V8 always feels strong, gutsy and is happy to be revved hard. Plus, the growing noise from that Mike Peach-built V8, further adds to the experience that cars like the XJ-S with its whisper-quiet V12 miss out on.

Although the physical throws between each gear are longer than the M1 motorway, with the ZF ‘box not feeling notchy or vague, as I quickly approach a corner I’m still able to flick the lever down into third relatively smoothly.

Body roll has been largely kept in check meaning fast corners don’t unsettle the car and there’s little worry of losing the rear on this dry autumnal day, but I’m still always aware of the car’s bulk. A fast change of direction or becoming overly confident could end messily.

With reasonably accurate steering and close to 50/50 weight distribution, I’m able to balance the throttle at a high speed through the bend before nailing it on the exit. With so much torque at my disposal, the V8 again responds instantly, rewarding me with another hard burst of acceleration.

Yet what strikes me most about the car isn’t the power or the performance but how civilised it is compared to the previous V8 model. Easy to drive, relatively refined and with supple suspension that makes light work of any imperfections in the road, clearly it’s more of a grand tourer than a pure sports car. The poor 15mpg fuel economy aside, I could imagine cruising down to the French Riviera in ultimate luxury.

Why, then, has the car been so overlooked since the day production of its updated replacement, the almost identical V8 Coupe, finished in 2000? I reckon the more angular design doesn’t help, arguably lacking the classic lines of the V8 that preceded it or the perfect proportions of the Vanquish that came after.

Plus – and in the Aston Martin world, this is important – it was never driven by James Bond, the secret agent preferring BMWs when the Virage and V8 Coupe were in production during the Nineties. This meant the car never had the exposure of its more famous siblings, never becoming part of British culture like the DB5 is now.

As a result, a Virage 5.3 coupe like the one featured can still be bought for around £50,000, around £25k less than what a Vanquish is currently worth. I’m sure over time that will change; the car is too memorable and its heritage too strong for it to be overlooked forever. But until that happens, this handsome, powerful and distinctive sports car will remain Aston Martin’s mystery machine.