The development of the Bentley Continental R was a story of savvy management decisions and engineering triumphs

Words: Ian Adcock

It’s 11.30am on Tuesday 5th March, 1991. It’s press day at the Geneva Salon and the crowds surrounding the Bentley stand are ten deep with journalists and photographers elbowing each other for the ultimate vantage point, me amongst them. All we had was an enigmatic invitation to attend a Rolls-Royce/Bentley press conference… and that was it. Although there had been rumours of a new Bentley, the stand was decked out in the blue and silver of Rolls-Royce, with the linked Rs and Spirit of Ecstasy dominating the walls.

It wasn’t until a forty-second video presentation had finished – during which time Bentley logos had replaced the Rolls-Royce graphics – that it started to dawn on the gathered media that this could indeed herald the arrival of a new Bentley.

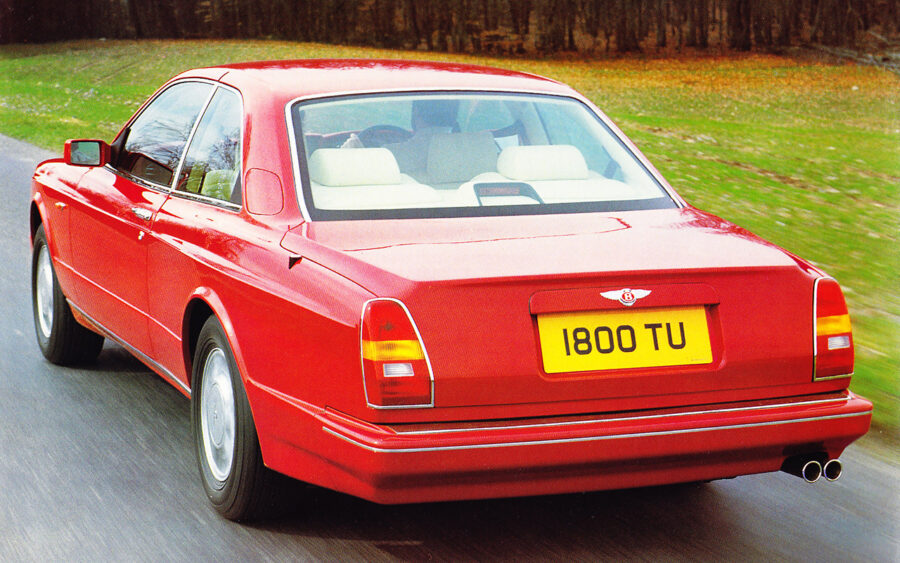

Presentations from Malcolm Hart, Mike Dunn and Peter Ward – director of sales and marketing, engineering director, chairman and chief executive respectively – then confirmed it was a Bentley. The car remained absent, however, until a Turbo R on display was slowly driven off the stand to be replaced by a Vermillion Continental R, driven by a very nervous Dave Preece to the unrestrained accompaniment of Elgar’s ‘Zadok the Priest’, which then faded away to allow ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ to boom from the speakers. For the first time ever, the organisers of the Geneva Salon had formally allowed a car to be driven on to a stand accompanied by music. It was a very special moment for all at Bentley; and anyone who has witnessed the Last Night of the Proms or rugby at Twickenham will have an inkling of the pride felt by the many Brits attending that show.

As the Continental rotated on its turntable, I glanced across at the Mercedes-Benz stand, where the new 600SEL V12 was being ceremoniously unveiled, the metallic silver paint glinting under the hall’s harsh lighting, witnessed only by a group of Boss-suited executives wearing three-pointed star lapel badges, handing out a few business cards bearing a Stuttgart address to anyone passing by. They looked as lost and confused as Franz Beckenbauer did at Wembley in 1966.

In twenty magical seconds, Bentley had stolen the Geneva Salon and announced that it was, well and truly, out of the shadow of Rolls-Royce.

Coupés had long been a feature of Bentley’s heritage, of course, dating back to Barnato’s Gurney Nutting-bodied Speed Six, through to the one-off Embiricos and various coachbuilt specials from Farina and Abbott. Most influential, however, was Evernden and Blatchley’s R-Type Continental, a personal favourite of mine.

Despite its glorious back catalogue, Bentley suffered long-term decline in the post-war years, becoming little more than a badge-engineered version of the equivalent Rolls-Royce, although its lower production numbers actually made it more exclusive than its parent marque. Even the development of a Bentley Camargue Turbo – designated DZ – was abandoned in January 1981, although its specifications subsequently formed the underpinnings of what morphed into the Bentley Mulsanne Turbo.

Paradoxically, through the post-war decades, the mythology surrounding the Bentley marque grew stronger, and it was only a matter of time before the suits occupying ‘Mahogany Row’ – so called, because that’s what all the directors’ doors at Crewe were fashioned from – would realise that Bentley was an untapped asset. The Mulsanne Turbo’s launch in 1982 gave Bentley a product that related to those heady days of Le Mans victories half a century back, for here was a car that (despite all its flaws, of which there were many) appealed to a new generation of younger, owner-driver entrepreneurs who appreciated the Bentley legend.

With that realisation came an influx of new, younger management to Pym’s Lane, executives who weren’t afraid to question the shibboleths of Rolls-Royce and Bentley, how the cars were engineered and built, how the company was run and, if it was to survive, what its customers actually wanted.

Spool back through the history of the British motor industry and 1983 will go on record as its nadir. In the midst of a global recession, Rolls-Royce and Bentley were fading, with conservative management clinging desperately to a ‘them’ and ‘us’ philosophy of industrial relations and arcane working methods. Sales slumped from a projected 3400 cars to just 1500, and the workforce went on a crippling strike in the October and November – the first in 23 years, and a year after 1200 colleagues had been made redundant. If you walked into a Rolls-Royce or Bentley showroom, you could even – horror of horrors – get a discount.

It was at this point that Ward, Hart and Dunn walked into Pym’s Lane with others like John Stephenson, the company’s first-ever product planning director. The trio came from different automotive backgrounds: Ward was the former head of Peugeot Talbot’s Motaquip spare parts operation, Dunn was a leading light behind Ford’s then revolutionary ‘jelly mould’ Sierra, and Stephenson had been part of BL’s product planning department.

Until the early 1980s, Rolls-Royce Motors was predominantly engineering-led. Marketing and customers alike were told what they ought to have rather than customers getting what they wanted, with new-model introductions dictated by engineering timescales rather than a pre-determined sales strategy.

It was decided that a project team, led by John Lake, should be established at Mulliner Park Ward to investigate various niche products, with inputs from Ogle design, Jankel, Heffernan and Greenley. And as Bentley started to assert its independence through products like the entry-level Eight, there was a growing realisation that the marque’s less formal grille brought great potential, particularly for a two-door coupé – an idea that eventually emerged as Project 90 at the 1985 Geneva Salon.

Project 90 – or Black Rat as it was quickly dubbed at the factory – was more than just a concept car. By the time it appeared, it had gone through virtually a full engineering programme, including 200 hours of wind tunnel testing with quarter-scale models at Southampton University’s facility prior to validation with a full-scale model at MIRA’s wind tunnel.

Those early tests predicted a 0.35 Cd figure (not bad for such a bluff-fronted car) as well as revealing some serious shortcomings, including 80% higher rear lift than a Mulsanne Turbo and a 50% increase in yaw caused by the centre of pressure being significantly further forward. Various rear spoilers were tried but ended up diminishing the car’s aesthetics, while concern over wind noise and dirt deposition demanded detailed work around the A-pillars and header rail from the design team.

Usually, designers aren’t that fastidious about concept cars since that is exactly what they are: concepts. But to win Crewe’s approval, John Stephenson knew that Project 90 had to look real, with a chance of series production based on the contemporary Mulsanne Turbo floor pan and running gear. This was a challenge in itself, as basic engineering requirements like the scuttle height, engine mounting and cooling package couldn’t be re-engineered.

Meanwhile John Heffernan worked closely with Graham Hull and Martin Bourne from the Crewe design department to develop and design the car’s lipstick red interior, using modified standard seating and fascia. It was such attention to detail that fooled the press at the ’85 Geneva Salon into thinking that Project 90 was heading for production. What they didn’t appreciate was that it had two different profiles, with one side having a less pronounced ‘Coke bottle’ effect over the rear haunches.

Nevertheless, the car was generally greeted with enthusiasm by the media. The Germans and Americans appreciated its post-modernist looks, although the British press thought it a little too retro. What none of us knew at the time, however, was that we were in for a six-year wait…

The camp was split in two over Project 90’s future: John Stephenson was convinced that a limited-edition run of two- and four-door versions was viable, but Peter Ward as well as Heffernan and Greenley were less convinced: “Project 90 was fine for the 1980s but it wasn’t a Bentley for the 1990s,” Greenley was quoted as saying. Ward had more pressing matters on his mind, however, uppermost being a ten-year programme of investment, restructuring the factory and developing new models, as he explained to the author: “We had to have a solid infrastructure in place before we could even contemplate launching a top-of-the-range Bentley coupé.”

A more efficient component production and ordering process, called Manufacturing Resource Planning, was introduced in 1988 along with an almost continuous stream of model revisions. A new £20 million paint shop was opened and new work practices put in place, with demarcations between skills removed and new labour agreements signed. It was a £200 million gamble; but without it, Ward and his team were convinced that neither brand would have a long-term future.

While Project 90 proved there was an appetite for a new Bentley coupé, there was a realisation that existing products needed updating. Heffernan and Greenley produced about ten proposals for future models, the majority being replacements for the ageing Corniche, a model that dated back in design (if not in name) to the late 60s. Between 1985 and 1987, these gradually morphed towards Bentley, with a growing belief that if the Corniche was updated technically, its classic lines still had sales potential.

In 1986, Ward took over from Dick Perry as managing director, and twelve months later Project Nepal got the green light. Subsequent investment in tooling and engineering for the new coupé coincided, fortuitously, with global sales for both Rolls-Royce and Bentley growing in 1989 and 90.

Other changes were also afoot; the long-time head of design, Fritz Feller, had retired in 1984 but neither Graham Hull, manager of styling, nor Martin Bourne, assistant chief styling engineer, were promoted. Ward argued that freelance designers working with in-house experts would be a more imaginative design direction for each marque.

As Heffernan and Greenley busied themselves in a specially-built design studio at Hythe Road, developing what would eventually become the Continental R, Hull and Bourne were at Crewe investigating the feasibility of a two-door developed from a Mulsanne bodyshell by raking the windscreen further back, combined with a modest ‘Coke bottle’ line over the rear haunches. Good as these were, the management encouraged Heffernan and Greenley’s more radical approach for a heavily sculptured design fine-tuned by the clay modellers, who spent hundreds of hours highlighting the surfaces down to the last millimetre.

Simultaneously, wind tunnel lessons learnt from Project 90 were applied to quarter-scale models, and although 0.35 Cd was achieved, there was once again a problem with rear-end lift. To eliminate this, Heffernan and Greenley developed the fluted wing crowns leading to the large, flat rear deck whilst fine-tuning its relationship to the rear header and window, resulting in a 40% reduction in lift. While Graham Hull designed new cheater door mirrors that helped keep the side windows clear, Martin Bourne re-sculptured the radiator top tank and repositioned the vanes to obscure the mechanical hardware behind them. In the end, a Cd figure of 0.365 was achieved, significantly undercutting the saloon’s 0.42.

The final digitalisation of the gloss black buck was undertaken by the experts at International Automotive Design, who did the body-in-white engineering, taking 35,000 readings off one side of the car to make this one of the most complex digitalisations ever undertaken by the firm.

The easy route for the interior would have been to transfer the Turbo R’s in its entirety, but Ward and Hart were determined to have a unique four-seater with a through console and a floor-mounted gear shift. The interior concept might have been Heffernan’s, but Hull and Bourne turned it into a true Bentley, with their fine detailing of the veneers, leather and chromework. Similarly, the two obsessed about the external brightwork, wheels and location of the lights and indicators to ensure the project stayed true to Crewe’s obsession with perfection.

If the Continental’s styling was the most contentious issue, then its dynamics were equally challenging. The original Mulsanne Turbo might have had an impressive turn of speed for such a bulky car, but its dynamics left much to be desired and came under Mike Dunn’s scrutiny. Suspension design and development engineer Peter Hill worked alongside vehicle chief engineer Phil Harding to develop Bentley’s and Rolls-Royce’s suspension, culminating in the Automatic Ride Control that launched in 1990, appearing a year later in the Continental R.

Although Project Nepal was conceived to be essentially a re-bodied Turbo R floorpan, powertrain and running gear with a new wheel/tyre package (Avon Turbospeed 255/60 ZR 16), it quickly became apparent that the coupé suffered from a very harsh ride and no discernible improvements in dynamics caused by cracks appearing in the front section. Being a two-door, the car was stiffer from the A-posts rearwards, although the main problem was the front spring towers levering against the longerons, cured by using a pair of ‘shotguns’ running from the outer side of the spring towers back to the bulkhead.

The newcomer’s powertrain at launch was, to all intents and purposes, a carry-over from the saloon, with 314bhp at 4300rpm and 485lb.ft. torque at 2250rm. The challenge was to find a transmission capable of coping with those loads, with Crewe eventually settling on GM’s four-speed Hydramatic 4L80-E used in both car and light truck applications, suitably refined and developed over more than a million miles of testing.

As the development programme continued and more test mules were seen in public, there was growing concern that Project Nepal’s existence would be revealed ahead of its scheduled 1992 launch. Moreover, there were the first hints that the global market for luxury cars was shrinking. Although there was no sense of immediate panic at Crewe, at an operations meeting in October 1990 it was decided to debut the car at the following spring’s Geneva Salon – and impressively, the company’s engineering department met that challenge.

Launching the car early and then telling customers they couldn’t have one for twelve months was a risky strategy at a time when the motor industry was in recession. Within two weeks of the Continental R being unveiled, however, 600 cars (two years’ worth of production) had been ordered, each with a £20,000 deposit. It was the first time that such a deposit had been demanded for either a Rolls-Royce or a Bentley, but was instigated in an effort to deter speculators from ordering several cars and forcing prices up beyond the quoted £160,000.

The Continental R family – encompassing various updates and new-model designations during its successful career – remained in production for an impressive twelve years, bringing welcome extra revenue to Rolls-Royce Motors thanks to its positioning at the very top of the new-car price lists. More importantly though, the Continental R helped to safeguard Bentley as a separate brand, its future reassured thanks to the vision and determination of Peter Ward and the team he gathered around him in the 1980s.