BMW M and BMW Motorsport officially parted company in the 1990s, focusing on road and race cars respectively – and making big strides forward in both departments

Words: Bob Harper

The 1980s had been quite a time for BMW M; it went from being a primarily motorsport-orientated concern at the beginning of the decade to a producer of some of the finest sporting machinery on the planet. The M car lineup had expanded with two generations of BMW M5, one BMW M6, plus the all-conquering BMW E30 M3. As the company set out for the 1990s, it was looking forward to expanding its horizons.

The models in production as the new decade dawned were the E30 M3, the E30 M3 Convertible and the 3.6-litre version of the BMW E34 M5, with the latter two models both being hand finished at BMW M’s headquarters. Expansion in the 1990s would see a change from this bespoke finishing of its products with all future models taking a leaf out of the E30 M3’s book with assembly being completed on the standard production line.

The first new model of the decade was the debut of the 3.8-litre incarnation of the E34 M5. While the 3.6-litre version had sold well, eclipsing the E28’s 2,241 examples with ease, there had been some muttering that it perhaps wasn’t quite as much fun as the original. Part of that was because the E34 was simply a much more refined product, but nevertheless there was a comprehensive overhaul of the model. Capacity swelled to 3,795cc making it the largest capacity straight-six ever produced by BMW; power was upped by 25hp to 340hp while torque was up by almost 30lb ft, making the M5 a sprightlier performer.

There was far more to the engine than a simple capacity increase; it featured larger valves, lighter pistons and an increased compression ratio, along with larger throttle bodies and Bosch Motronic 3.3 with six individual coils. There were tweaks to the chassis, with an adaptive electronic damper system being added – switchable if the optional Nürburgring package was ordered. The extra power brought out the best from the updated chassis and the plaudits flowed for the M5 3.8. For the first time the M5 was available as a Touring, and while it was left-hand drive only, it did demonstrate that M was willing to expand its product portfolio into unknown territory.

Of course, the BMW 6 Series had been replaced by the all-new BMW 8 Series, and while it was a very different beast to the car it replaced, M’s engineers were keen to demonstrate their abilities on the range-topping model. Sadly the BMW M8 that was developed didn’t come to fruition as the board decreed that it would have been too expensive – but the development work didn’t go completely to waste as the 850CSi would prove.

Not badged as an M car, it was nonetheless developed by M and wore the coveted WBS chassis number prefix which denotes a BMW Motorsport product. Powered by an M-fettled V12 known as the S70, the 5,576cc unit developed 380hp and was mated to a six-speed manual gearbox. Suspension changes ensured sharper responses and in Europe this was partly down to the advanced rear suspension set up with Active Rear Axle Kinematics, which allowed a modicum of rear-wheel steering to enhance agility. The car was relatively short-lived and didn’t sell in huge numbers – just 1,510 were made, which makes the S70 in the 850CSi the M engine with the lowest-ever production volume. Further versions of this engine would feature in other models.

The BMW E36 M3 Evo was a development of the original E36 M3.

Then there’s the small matter of the BMW E36 M3 to discuss. Over the years the E36 has often been labelled as the runt of the M3 litter, but that’s being so unfair on the car – it was a huge hit and doesn’t receive the credit it deserves. Replacing the E30 was always going to be a tough gig, but especially so as the E36 was to be a road car and didn’t therefore have the racing DNA that made the E30 such a huge success. It made its debut in 1992 and was bigger and heavier than the lithe E30, which didn’t help its case with the enthusiasts. The E36 M3 received a lot of criticism despite a number of impressive technological developments; the 3.0-litre straight-six produced 286hp, meaning a specific output of 96hp per litre, which BMW claimed was the best of any naturally aspirated road car. 0-62mph in around six seconds and a 155mph top speed were the result.

The problem was that it just wasn’t special enough. The E30 looked the part, built for the road but around a racing design; the E36, on the other hand, was to become indistinguishable from a million 318is with body kits. Despite the visual shortcomings the E36 sold well, and while the motoring press mourned the loss of the E30’s sweet steering and tactility, the E36 was the better all-round road car offering better refinement with the ability to entertain. US models received a less powerful engine to keep costs down but despite this Road & Track magazine called it the best-handling car in America when it was new, besting stiff competition from the likes of the Honda NSX, Ferrari F355 and a Porsche 911 Carrera S.

As is often the way – witness the changes made to the E34 M5 – BMW M was perhaps stung by some of the criticisms directed at the E36 M3 and in 1995, after three years in production, the M3 received a host of significant changes and became the M3 Evolution. The engine grew, power rose to 321hp and there were a number of chassis revisions; the Evo was phenomenally quick, the engine was great, and while it was still more a refined cruiser than an out-and-out sports car, the M3 was now an awesome all-round performer.

The E36 M3 was also the first M car to be offered in more than two guises, being available as Coupé, Saloon and Convertible. The Coupé was always the biggest seller but there was plenty of appetite for the other models, and in total BMW sold over 71,000 E36 M3s of all types; this eclipsed the E30’s 17,970, proving that while it might not have had the delectable responses of the original M3 perhaps the buying public were after a more rounded proposition.

However, we need to rewind a little to 1993, as by this time it was clear that BMW ‘Motorsport’ was actually far more closely aligned with road cars than it was with racing activities and in 1993 BMW M GmbH was formed, which would deal exclusively with road cars. Under the umbrella of BMW M GmbH came five distinct departments, employing over 450 people in three locations around Munich. As well as the familiar road cars and M Technik side of the business, BMW M also became responsible for the company’s driver training programme and BMW’s Individual arm too.

While we’re going to concentrate on the road cars here it’s worth remembering that BMW Motorsport – now fully committed to racing – had plenty of projects on the go, too. Race cars based on the E36 might have lacked that all important M badge but they all had M-Power under the bonnet and the Super Tourers dominated races and championships around the world. BMW E36s won five Nürburgring 24-Hour races in a row between 1994 and 1998, three with an M3, one with a 320i and the first diesel-engined machine to win, a 320d, in 1998. There were five overall wins at Spa in the same years too. E36 M3s won the IMSA GTS-2 title in the US in 1996, 1997 and 1998 as well as the ADAC Cup in Germany – further proof that it was a wonderfully versatile machine.

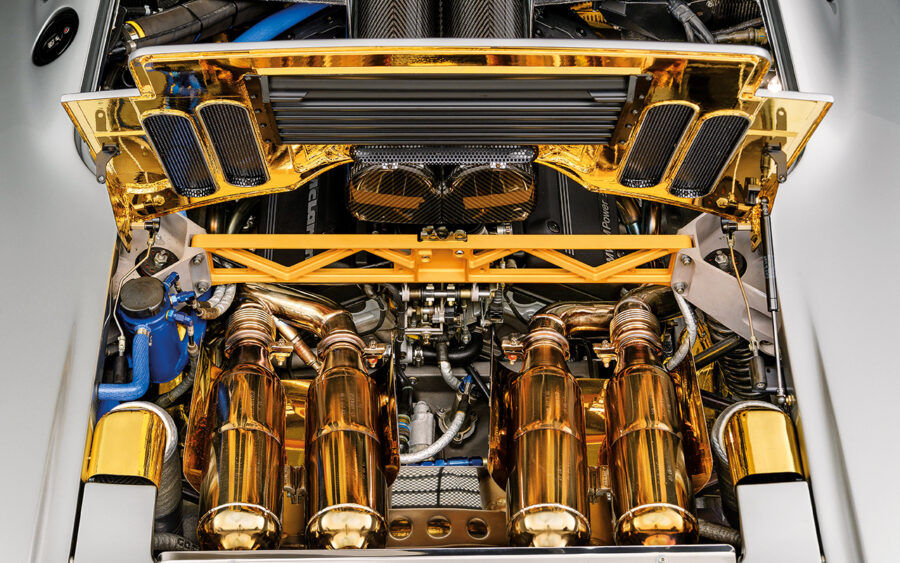

The unmistakable gold-lined engine bay of the McLaren F1.

Perhaps now would be a good time to come back to that S70 V12 we talked about earlier as it was, of course, used in one of the finest supercars to ever grace our roads. We’re talking about the McLaren F1 here and its engine was designed by BMW Motorsport’s Paul Rosche. Gordon Murray’s requirements of the engine for his supercar were demanding to say the least: it needed to develop 550hp, be less than 6000mm in length and weigh no more than 250kg. It would also have to be naturally aspirated. Rosche had already developed a V12 for the stillborn M8 and had gained further experience with the 850CSi, but the S70/2 that was destined for the McLaren F1 was an absolute masterpiece.

It featured four cams, 48 valves, two plugs per cylinder and an 11:1 compression ratio. The engine was everything Murray needed it to be. Despite being six percent heavier than he had hoped, it was also 14 percent more powerful, and within the 600mm target. The S70/2 developed 627hp at 7,500rpm, with 470lb ft of torque between 4,000 and 7,000rpm – good enough to propel the F1 from 0-62mph in 3.2-seconds and onto its headline-grabbing 240mph top speed. The McLaren F1 won at Le Mans in 1995 and the same engine would go onto win the event outright for BMW with the BMW V12 LMR in 1999.

While the Motorsport side of the business was doing very well there was a brief time when there wasn’t a BMW M5 in the line-up – the E34 ceased production in 1995 – and the only M car was the E36 M3. What else could M fettle? The answer was the Z3. Officially known as the E36/7 M Roadster, the top dog in the BMW Z3 range was designed to add a little panache to BMW’s roadster range – which was going to look a little old hat when the likes of the Porsche Boxster arrived. Slotting the E36 M3 Evo’s straight-six under the Z3’s retro bonnet could have been a step too far as the Z3 still made do with the E30’s old trailing-arm rear suspension setup, but a host of revisions ensured that it wasn’t quite as wayward as it could have been.

The front and rear tracks were widened, the ride height was reduced and firmer springs and dampers were employed. Additionally, the M Roadster featured thicker anti-roll bars, a reinforced rear subframe and stronger rear trailing arms and the front suspension geometry was altered too. Wider wheel arches, a set of quad exhausts – the first for an M car – and a set of seriously good looking 17-inch alloys completed the package. It was certainly a brawny machine and while it didn’t have the delicate handling balance M had become renowned for it was certainly quick and a hoot to drive, even if the Z3’s slightly wobbly structure couldn’t be fully disguised.

In an attempt to give the Z3 M some of the rigidity it was sorely missing, project leader Burkhard Göschel embarked on a bit of a skunkworks project with some of his staff to create the Z3 Coupé. Persuading the board to put it into production wasn’t an easy task but he was given approval once it was clear it wouldn’t be costly to rework the Roadster to a Coupé. It was certainly a better bet than the Roadster from a driver’s perspective and has subsequently become a BMW cult hero.

And talking of cult heroes, the 1990s also brought one of the very best M cars created to date: the E39 M5. By now the arrival of an M5 was eagerly awaited but the E39 generation’s debut took some time –and there was even a school of thought that BMW would simply make do with the 540i as its range-topping 5 Series. Fortunately those fears were unfounded, as the M5 made its debut at the Geneva Motor Show in 1998, with production commencing toward the end of the year. Right-hand drive buyers would have to wait until 1999 to get their hands on one.

The arrival of a new M5 was much anticipated – the E39 did not disappoint.

The E39 M5 was the first M car to feature a V8, and given how BMW M had been extracting a huge amount of power from smallish engines, its specific output of just 80hp per litre was perhaps a little disappointing – especially compared to the E36 M3 Evo’s 100hp per litre. And where were its fancy exhaust manifolds? Surely those weren’t stock E39 V8 fare? Had M done half a job on the E39 M5?

Not a chance – it was a sublime machine. With 400hp and 369lb ft of torque is was fast and flexible, willing to rev to its 6,600rpm power peak or slug it out at lower rpm. There were a host of changes under the bonnet, starting with an increase in bore and stroke for a 4,941cc capacity and extending to individually electronically controlled throttle butterflies, double VANOS, modified cylinder heads, oil-cooled pistons and a lubrication system with two scavenge pumps to ensure no oil starvation occurred during prolonged high speed cornering. It was a masterpiece that not only produced the goods but sounded divine while doing so.

The E39 5 Series’ underpinnings were thoroughly revised, beefed-up and honed, the brakes were uprated and the E39 M5 became the first M car to feature a fly-by-wire throttle setup. This allowed for a ‘Sport’ button that sharpened throttle response and allowed for a Dynamic Stability Control system to be fitted to an M car for the first time. All in all it was a stunning machine – and in the best M5 tradition, it was subtly muscled and didn’t shout about its ability.

All in all, the 1990s was a great decade for BMW M, with an extensive model line up of cars that were selling in greater numbers than ever while seemingly not losing the cachet of the brand.