BMW Motorsport was founded in 1972 at the dawn of a golden era for the brand’s racing efforts. Here’s how BMW M found its feet

Words: Bob Harper Images: BMW

As 2021 rolled to a close BMW M GmbH celebrated its most successful year yet, having shifted over 160,000 M cars along with countless M Sport models too. It’s a far cry from the company’s first year in business when it was known as BMW Motorsport and had a scant 35 employees – we don’t imagine many of those who started working for the company back in 1972 would have dreamed quite how far BMW M would come over the ensuing decades.

While BMW Motorsport was formed in May 1972 to oversee BMW’s on-track activities, it would be another six years before the first road car bearing an M badge would see the light of day. It’s also important to remember that at this time the resurgence of BMW was still very much in its infancy – it had been rescued by Herbert Quandt just 13 years prior to the formation of BMW Motorsport, so it’s impressive that BMW was willing to become a fully paid-up member of the ‘win on Sunday, sell on Monday’ club.

1960s

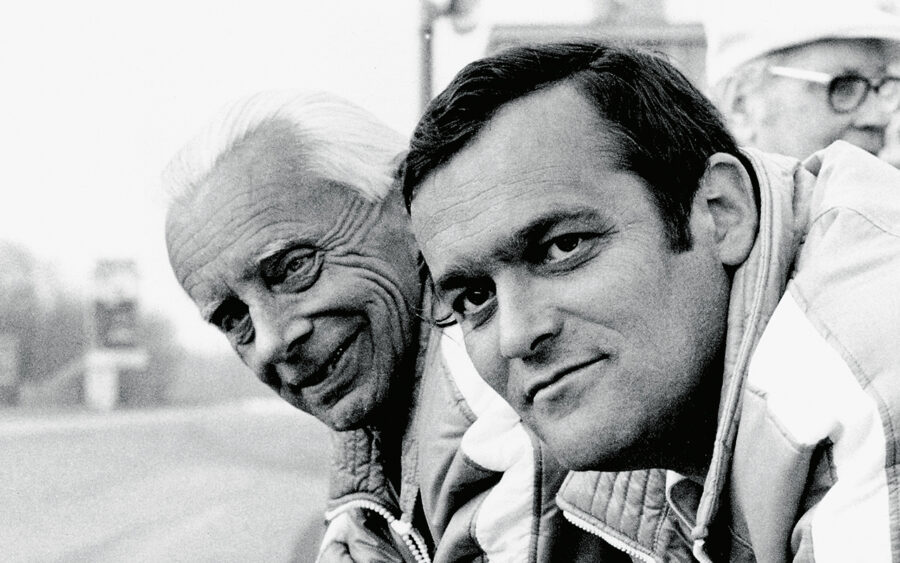

It hadn’t always been that way; during the 1960s, BMW did have a certain amount of success with its competitions department. BMW’s engine guru Alexander von Falkenhausen, along with his protégé Paul Rosche, would develop the Neue Klasse saloon into a championship winner as early as 1964, with Hubert Hahne winning 14 of 16 races to become German circuit racing champion. A 12-hour touring car victory at the Nürburgring followed along with a 24-hour win at Spa-Francochamps in 1966. The new BMW 2002 machinery was also successful, with Dieter Quester winning the drivers’ and manufacturers’ titles in the 1968 European Touring Car Championship (ETCC).

There was also some involvement in F2 in the late 1960s, and even when BMW pulled the plug on the campaign, a skunkworks project continued off the books, with von Falkenhausen, Rosche and a few other employees continuing to develop the engine at evenings and weekends. The engine was installed in a March chassis and Dieter Quester finished third overall in that season’s championship – not a bad effort given a lack of factory backing. Development of the touring cars – and in particular the BMW E9 Coupés – was more or less left to privateers such as Alpina and Schnitzer, but BMW must have been keeping an eye on their efforts and could see that success on track wasn’t too far away.

Alexander von Falkenhausen and Paul Rosche, 1967

1970s

Ford was ruling the roost in the ETCC and after an about-turn at board level, BMW elected to reinvest in motorsport and decided the best way to do this would be to poach the head honchos behind the Ford Capri’s success. So it was that in May 1972 Jochen Neerpasch and Martin Braungart joined BMW – and BMW Motorsport was formed.

It was too late to win the 1972 title but after a crash diet, chassis work and Paul Rosche further developing the engine, the CSL was just about ready for the start of the 1973 season. With a 3.3-litre version of the straight-six and Kugelfischer injection, Rosche had eked around 350hp from the engine and the team went to the opening round at Monza with high hopes. Best laid plans didn’t bring the rewards, with both factory CSLs suffering from engine failure – a feat also managed at the next race. Changes were made and to ensure reliability two factory CSLs were entered in the 24 Hours of Le Mans up against three Ford Capri racers as their main class rivals. Hezemans and Quester brought home a CSL as class winner and 11th place overall.

While this was a great result, perhaps the most important CSL component – the Batmobile wing kit – was homologated mid-season by Neerpasch and turned a good race car into an all-conquering one, with Hans Stuck reckoning it knocked 31 seconds off the CSL’s Nordschleife lap time. The factory CSLs would go on to take the championship in 1973 and private teams (with a certain amount of factory backing) would go on to bag the ETCC every year from 1975 to 1979 – an amazing feat for a car that first saw the light of day in 1968.

Of course, there needed to be a road car for homologation purposes; the 3.0 CSL might not have had an M badge but it was certainly the first machine to emerge from the fledgling department. In fact, the first CSLs were built and conceived by the competitions department in 1971 with carburetted standard M30 engine – it wasn’t until September 1972 that fuel injected 3,003cc machines were produced in both right- and left-hand drive formats. The iconic Batmobiles with their 3,153cc engines and wing kit (supplied in kit form so as not to fall foul of German regulations) were made in two batches in late 1973 to January 1974, and again sporadically during 1974 and 1975. The CSL could be ordered with the now-famous M tricolour stripes.

There was another machine developed by BMW Motorsport, drawing on experience gleaned with the turbocharged BMW 2002 used in the ETCC in the late 1960s. The road-going 2002 Turbo didn’t see the light of day until the latter part of 1973, and while it wasn’t the world’s first turbocharged road car, it was the first from a European manufacturer. It was a 2002 with real menace – pumped-up arches, a rear spoiler and some seriously beefed-up underpinnings.

The engine was the 2.0-litre unit with a lowered compression ratio, a KKK turbocharger and Kugelfischer injection. It boasted headline figures of 130mph and a 0-62mph time of just 6.9-seconds, but thanks to the length of the drainpipe-sized turbo pipework it could also suffer from monumental turbo lag and earned itself a reputation for spiky handling if boost arrived mid-corner. It was an interesting side project for BMW Motorsport but was ultimately killed off by the fuel crisis after just 1,672 examples were built. Lessons learned from the build did come in use for another project later in the decade, however.

While BMW might have built its racing reputation with tin-tops during the 1970s it’s important to remember that BMW Motorsport also went on to be spectacularly successful in Formula 2. Factory backing might have been withdrawn in the early 1970s but having seen what could be achieved with a skunkworks project, BMW gave its backing to a factory effort run by BMW Motorsport. The engine for the F2 machine was based on the road-going M10 unit but had the M12 designation for its racing career, and in 1973 BMW Motorsport did a deal with British race car constructor March Engineering to exclusively supply BMW engines for its F2 chassis. It was an almost perfect season, with March works driver Jean-Pierre Jarrier winning eight races and placing second in a further two giving him the championship win. During the life of the 2.0-litre F2 category, BMW engines would go on to win 90 out of 150 races and would give BMW-powered drivers six European F2 championships.

Having tasted success in virtually every arena, BMW Motorsport’s boss Jochen Neerpasch was keen to demonstrate what his fledgling enterprise could achieve and pushed hard for a stand-alone model that would prove BMW was a bona fide manufacturer of sports cars that could also do battle with the best on track in Group 4 and Group 5 racing. The result was the iconic BMW M1 – but its protracted gestation period was almost its undoing. The M1 was project was signed off by the BMW board in 1976 on the understanding that its production would not impinge on the manufacture of the rest of the BMW range.

Sporting regulations stipulated that 400 examples had to be produced in a 24-month period; in order to achieve this without assistance from the BMW factories, Neerpasch knew that production would have to be outsourced. A deal was struck with Lamborghini to assemble the M1, with engines being shipped to Italy from Munich; prototypes were seen trundling around Sant’Agata as early as 1977. However, while things initially seemed to be going according to plan, it soon became clear that Lamborghini wasn’t up to the job and Neerpasch’s hopes of a Geneva motor show reveal in 1978 – and a competitive debut later that year – simply wasn’t going to happen. Eventually a Paris debut was made in 1978 but homologation wouldn’t happen until 1981, by which time rules had changed and the BMW M1 wouldn’t have been competitive.

The M1’s production turned into an incredibly complex series of manoeuvres with the Giorgetto Giugiaro penned fiberglass bodies being produced by an Italian company, TIR, while the Lamborghini-designed spaceframe chassis was manufactured by another Italian company Marchetti. The two were mated together and painted at Ital design before the part completed M1s were sent to Baur in Germany where the running gear was fitted. Completed cars were then sent to Munich for final checks and road testing. This was overseen by Paul Rosche and the reality was that much remedial work had to be carried out in Munich before the cars were ready for customer handovers. Despite all these problems the M1 was a glorious machine with a mid-mounted M88 24-valve straight-six that developed 277hp at 6500rpm and 239lb ft at a heady 5000rpm.

With no sign of homologation on the horizon Neerpasch managed to get the M1s on track in the now famous Procar series that accompanied the F1 circus in 1979 and 1980. F1 drivers of the day competed against up and coming drivers from other disciplines and the sight of full grids of race-prepped M1s duelling on F1’s famous circuits was certainly spectacular with Niki Lauda winning the inaugural championship.

The M1 Procar series accompanied F1 in 1979 and 1980.

Not content with dreaming up and getting a mid-engined supercar into production Neerpasch needed a new tin-top contender and when the first generation of 3 Series arrived in 1975 work soon began on turning it into a successful racer. Initially privateer teams were left to do the work but given some successes in 1976 BMW put money behind a factory team for 1977. Neerpasch had the idea of using its hotshot young racers and the BMW Junior Team was born. It consisted of Eddy Cheever, Manfred Winkelhock and Marc Surer and together they entered Group 5 racing.

The rules were pretty fluid which meant that BMW Motorsport could effectively run its hugely powerful F2 engine in the 320i’s shell – that equated to 300hp at 9,250rpm in something that weighed just 765kg, endowing the 320i with a 0-62mph time of around 4.5-seconds and 0-100mph in less than eight seconds. The young drivers tended to treat many of the races as high-speed demolition derbies and famously Neerpasch became so enraged that he banned all three of them for one race weekend, replacing them with older hands who were slightly more inclined to bring the cars home in one piece. Fortunately the Junior Team did manage to accrue enough points during the season to take the title in 1977.

A further development was an interesting one – Schnitzer introduced a turbocharged version of the 320 in 1978 and soon had the 1.4-litre four pot developing well over 400hp. BMW Motorsport further developed the unit and discovered that well over 600hp was possible and this made Neerpasch decide that a turbocharged F1 engine could well be produced by BMW. He approached some of the top teams and had more or less agreed a deal to supply McLaren with BMW engines for the 1980 season and presented this as a fait accompli to the BMW Board who were less than impressed that this had been done without their knowledge. Approval was denied and thus Neerpasch, the driving force behind BMW Motorsport since its inception, left the company in 1979. It wouldn’t be the end of the F1 story though, but that’s a tale for the next instalment of our BMW M story.

More or less the last task for BMW Motorsport in the 1970s was the fettling of the E12 5 Series to create the blueprint for generations of M5 that followed. The E12 M535i made its debut at the Frankfurt show in 1979 and while it might not have had the four-valve head that’s become such an M trademark it was a quite superb sports saloon. BMW Motorsport had been quietly converting E12s for favoured customers for quite some time but this was the first official version that utilised the 3453cc version of the venerable M30 ‘six which was good for 218hp. With revised suspension, brakes, an aggressive aero kit and a more sporting interior it would lay the foundations for BMW’s sporting saloons for decades to come.

From small beginnings BMW Motorsport achieved so much during the 1970s, fettling road cars into proven race winners, winning numerous single seater titles as well as developing and producing a mid-engined supercar from scratch. It was a very promising first few years for the company that would go on to be the most powerful letter in the world.