The BMW Z1 was a test bed of ideas intended to revive its maker’s sports car heritage. Here’s the story of its development and significant impact

Words: Jon Burgess Images: BMW

Z3, Z8, Z4: chronologically confusing, but a well-defined line of sports cars. Of course, it was the 8000-unit Z1 that began the ‘Zukunft’ (Future) line: a car that, in isolation, was over-equipped for the 1990s roadster revival, but never really had any interest in participating anyway.

That the Z1 blazed a trail should never be forgotten; it revived a BMW roadster tradition last glimpsed in the limited-run 507, and before that, the pre-war 328 which, with its overhead-valve Fritz Fiedler-designed straight-six, was instrumental in the fortunes of the (post-war) Bristol Car Company.

The most lasting treasure the Z1 gave us was its newly-created and tested Z-axle; the aft suspension unit, with some refinement, ended up on the 1992-onwards E36 and, with further modification, under the boot floor of Rover’s 75 (R40), banishing the evil vicissitudes of BMW’s trailing arm rear ends to the history books.

Alas, we need to go back another decade to fully understand the Z1’s story – to 1985, in fact, when a new department, BMW Technik (Technology) GmbH was formed, a stone’s throw from the Group’s main factory and development areas in Munich. Best described as a think tank for new ideas, technologies and materials testing. the 60-strong group, headed by director, Dr Ulrich Bez, was tasked with working on new and more efficient ways of building BMWs.

Technik wasted no time in sketching out a new sports car – a low volume model that could act as surrogate for mainstream BMWs. Newly employed designer, Harm Lagaay, on his first Porsche sabbatical, worked with engineers on a radical proposal for a mass-market manufacturer: a steel monocoque with removeable plastic panels. A shooting brake and a roadster both made it to mock-ups, with management overwhelmingly preferring the latter.

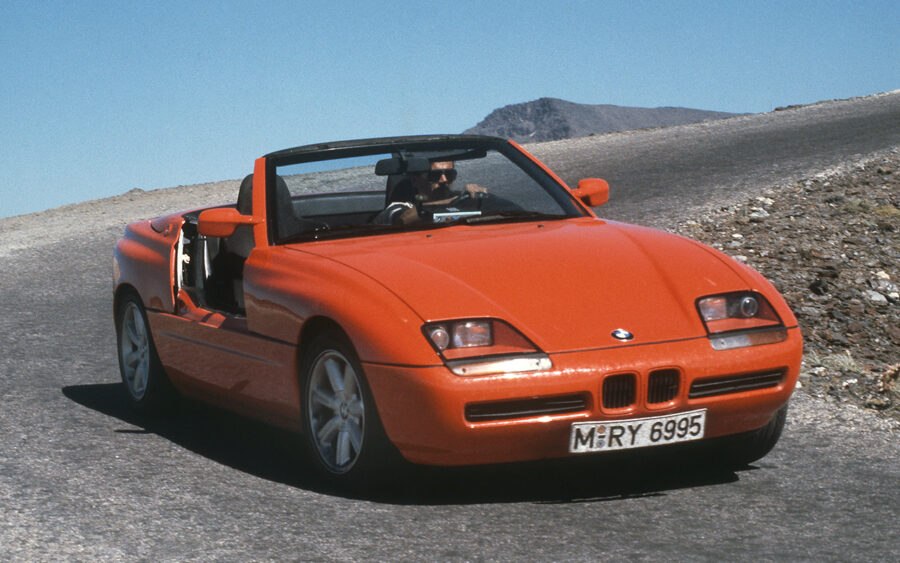

BMW Z1 prototypes testing in 1986

Truth be told, the process taught BMW a great deal about new methods of facelifting cars; Pontiac’s Fiero (P-Car) and Renault’s Espace had also dabbled with plastic panels atop steel superstructures. To all intents and purposes, the panels, later formed from General Electric’s polyester and polycarbonate Xenoy, were meant to be easy to replace in the case of an accident – and straightforward to supplant should the customer want to change their car’s colour or update a Z1 with later, facelifted panels.

BMW also wanted the new car, now named Z1, to be agile, which meant its sometimes treacherous trailing arm rear suspension, present in the current E30 3 Series, had to go. An new rear suspension unit, nicknamed the Z axle, was developed during the Z1’s midst: it was far better at keeping the wheels at the correct angles during cornering and rid the new car of the vicious on-limit snap for which small BMWs were known.

The Z1’s steel skeleton, under development, allowed for BMW’s M20B25 2.5-litre straight six to be placed in a front-mid-engined configuration; eventually, with the new Z-axle in place, the car ended up with near perfect 49:51 weight distribution.

Intensive prototyping led to 78 pre-production cars being built between 1986 and 1987, the latter ten of which were fully driveable; one of which went on display at the Frankfurt IAA, to rapturous reception from press and public alike. BMW’s other great reveal, the V12-engined, 750i (E32), a magnificent achievement in itself (one which prompted a spectacular riposte from Mercedes-Benz a few years later) was overshadowed somewhat.

Fever pitch had been brewing since 1986, when earlier Z1s had been spied testing. Pert, modern and exciting, BMW was inundated with nearly 4000 pre-orders – builds it knew would take time to fulfil, owing to the new and novel way in which the car was constructed.

The hot dip steel in the monocoque was zinc coated in a move that not only aided rust resistance, but aided greatly in rigidity – by as much as 25 per cent, as it helped connect the car together, as well as bear loads. Plastic panelling wasn’t just used for the outer panels; co-developed with Messerschmitt, they also provided the Z1 with a flat floor, stabilising air flow under the car and helping its extremities achieve downforce.

There were no doubts in BMW Technik’s mind that Xenoy plastic panels had their place: at IAA, Technik’s director, Dr Ulrich Bez, jumped up and down on key Z1 panels, only to have them spring back into shape. BMW’s ambitions to sell full sets of differently coloured panels to Z1 owners, and facelifted parts at a later date, went mostly unrealised.

Of course, the Z1’s much vaunted and discussed doors were key to its appeal; so rigid were its massive box section sills that they passed what side-impact intrusion requirements there were easily, allowing them to be fully dropped in motion, should the driver wish.

A complicated mechanism was responsible for making the retraction happen; in later years, BMW was eager to demonstrate their operation; they made a great spectacle of the febrile ideas and technologies Technik had under development. The Kaiser Darrin pulled its doors fore, into its wings, the Saoutchik-bodied Graham-Paige Type 97 pulled them aft, while the later Joalto Lincoln MkVIII rolled them under the car entirely.

The Z1’s retractable doors boasted fewer mechanisms and electronics than any other system before or after, calling into mind the near go-kart sensations of riding along the road in a low scuttle, short doored British roadster like the Triumph TR2. That the Z1 could provide such experiences while meeting modern safety legislation said much for the efficacy of Technik’s engineering.

In many ways, the Z1 was a classic British sports car re-imagined for the modern age. While Mazda reanimated the MGB in its MX-5/Roadster, and Lotus innovated in drivetrain and suspension for its radical Elan M100, the Z1 called to mind a trimmer, more advanced big Healey or TR5/6: a wheel at each corner, a simple, foldable roof, a six-cylinder engine, and rear-wheel-drive.

By October 1988, production had begun in a dedicated corner of Munich, beginning with six units a day and rising to as many as 20 cars a day by 1990, though 16 cars was a more realistic workload for Technik to manage. Z1s were labour intensive cars to build, which added to their high price of 83,000DM – 3000DM more than first mooted, but for which people were happy to pay a premium for.

Intended mostly for a European audience, the Z1 remained left-hand-drive throughout its career, though British specialists, Griffin Motorsport, converted six cars to right-hand-drive, one a completely knocked down kit for a buyer in New Zealand whose Z1 had to be a right-hooker to be driven on the local roads. Tuners, Birds Autos, also made two right-hand-drive Z1 conversions of its own.

Alas, the sting in the tail came not from bumpy B-roads and inadequate rear suspension, but from the changing economic market. The effects of 1987’s Black Friday were beginning to trickle down into people’s pockets: there was less money to spend on frivolous cars, and what slowly began to hurt Porsche’s bottom line also did for the Z1.

While the music still played, however, enthusiasts adored the Z1, with some crying out for more equipment and more power. Low volume car maker Wiesmann stepped into the breach by offering a hard top option, while the likes of Alpina and Hartge, among others, concentrated on liberating more power from the M20B25.

It was the former boys from Buchloe which went the furthest in transforming the Z1, however: in 1990, when production was at its peak, and a few more colours were added to the Xenoy parts manufacturing line, it released the Roadster Limited Edition, a 2.7-litre, 200bhp Z1 with special paint, tyres and interior. 31 of the 66 cars produced between 1990 and 1991 went to Japan, a market which, like the UK, was more or less denied the Z1 apart from special order.

Demand had slowed by then – 1991 – as recession loomed and fewer orders were coming in than ever before. Bez and Lagaay’s brilliant baby had proved its point, BMW had another icon, and Technik’s place in BMW’s roster had been assured.

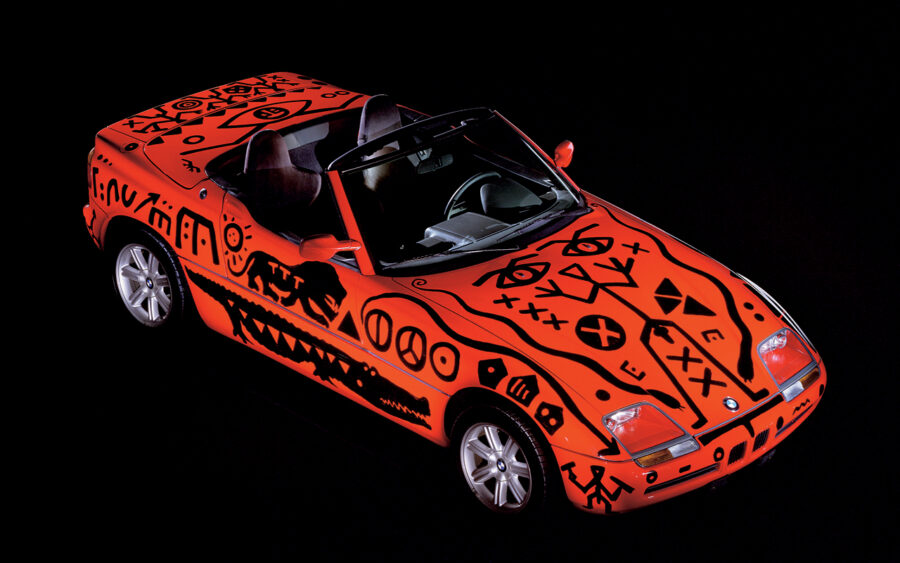

Artist AR Penck made a Z1 into the 11th BMW Art Car that year, too, and while Technik would never again be so responsible for a sports car (the 1995 Z3 was conventionally engineered and built mostly in Spartanburg, South Carolina, USA), it carried on tinkering with sports car concepts, notably the all-weather Z18, and back-to-basics Just 4/2 (Z21), neither of which saw the light of day after the show lights had been switched off.

Brilliantly unique in execution (at least in Europe), safety and emissions legislation means we will probably never see the likes of the Z1 again. They’re now collector’s items, adored the world over, and for an icon of technology, that’s strangely fitting.

BMW Z1 timeline

1985

BMW Technik GmbH formed, under the control of director, Dr Ulrich Bez.

First sketches of new car, project ‘Zukunft 1’ (Future 1) emerge; proposals include a roadster and a shooting brake.

Harm Lagaay’s roadster concept wins much favour among senior management.

BMW Z1 prototype pictured in 1985

1986

Testing begins; cars with (and without) bodywork spied by the press. Z-axle results from Z1 programme testing.

1987

Z1 concept roadster debuts at the Internationale Automobil-Ausstellung (IAA) in Frankfurt; on show was one of ten driveable pre-production prototypes (built from a run of 78 cars). Further road testing and development continues for series production. Around 4000 pre-orders are received.

1988

Production and sales begin in October in a dedicated area of BMW’s Munich works. 2.5-litre 170bhp M20B25 straight-six, rear-wheel-drive, Z-axle suspension; four body colours, four upholstery colours, three carpet shades.

Production at first manages six cars a day, later rising to 16-20 units, all in left-hand-drive, mostly intended for the German market, though Griffin Motorsport in the UK produced six right-hand-drive conversions, beginning this year.

1990

Z1 production hits its peak.

Alpina announces Roadster Limited Edition (RLE): 200cc capacity increase, 20-spoke alloy wheels, three-spoke Alpina steering wheel. 66 produced, nearly half the output heads to Japan.

1991

Z1 production ends after 8000 units, also ending the Alpina RLE run.

Artist, AR Penck, uses a red Z1 as the ‘canvas’ for the 11th (of 19) current BMW Art Cars.