We revisit the workings of Jaguar’s adaptive damping system marketed as Computer Active Technology Suspension (CATS)

Words: Paul Wager

I was chatting recently with former Jaguar engineers who had been involved with the development of the firm’s road cars from the mid-1980s right up to the aluminium-bodied XJ of 2002 and naturally the subject of ride and handling came up.

Jaguar may have had its issues, especially in the BL era when quality was suspect to say the least, yet one thing the firm always managed to offer was a ride and handling balance which was pretty unique in the market. The Mk2 and its predecessors may have been unremarkable in this regard, but once the famous independent rear suspension had been developed, Jaguars managed to combine capable roadholding with a remarkable composure, something which was first offered in the S-Type of 1963 when road testers all remarked on how much more comfortable and capable it was as a high-speed long-distance cruiser.

This unique Jaguar selling point would help the firm through some dark times when industrial unrest meant production quality was at rock bottom and for example, even when the XJ-S and Series 3 XJ were in the twilight of their production lives they were still winning praise in magazine group tests for the quality of their ride and handling.

Fashions were changing though and by the early 1990s a 15-inch rim with tall tyre sidewalls was increasingly looking old-hat as tyre profiles shrank and wheel diameters increased. A new era was beginning where a car couldn’t be considered sporting unless it offered a rock-hard ride – at least if it was German anyway – and Jaguar was in danger of losing its signature feature in following the fashion for 18-inch rims and 30-profile rubber.

However, this was also an era when electronic control in the automotive world was just gaining pace and active ride systems had already been demonstrated: Lotus had demonstrated a full active ride system on an Esprit as early as 1983 and in 1994 Citroën developed its Hydractive system into a production car as the Xantia Activa – both cars offering entirely flat cornering.

In practice though, full active ride systems weren’t quite what the market wanted and indeed the Lotus system never made it to production, while many Activas ended up in ditches when the lack of cornering sensation encouraged drivers to exceed the limits of grip and general laws of physics.

What was wanted was a solution aimed more at addressing everyday practicalities, specifically how to offer a soft ride during gentle driving on average roads, but firm up the suspension when the car was driven in a spirited manner and for this, automatic control of the dampers was ultimately the answer.

Yes, adjustable dampers had been around for a long time – since the very dawn of motoring in fact – and even a humble Austin Seven offered the facility to adjust the damping by hand, while many aftermarket suspension kits from the 1980s onwards offered a manual adjustment… if you were happy to get under the car with a spanner. Rolls-Royce offered its Active Ride system on the 1990-on Bentley Turbo R which took inputs from an accelerometer, throttle position and brake lights in order to operate hydraulic valves on the dampers and although it was in many ways an analogue system, it worked remarkably well to offer a ride which was cossetting in gentle driving but firmed up noticeably in spirited use.

What they didn’t offer though was a constant control of suspension in response to road and driving conditions and it was this which became possible with powerful microprocessors and high-speed communication.

This was the answer Jaguar needed and when the original XK8 was launched in 1996, one of the key optional features was the new Computer Active Technology Suspension – marketed under the tongue-in-cheek acronym CATS.

Like previous variable damping systems including that Bentley set-up, the basic principle behind CATS was to vary the damping characteristics in proportion to the force of body and suspension movements. Crucially, the Jaguar system was to be entirely automatic, unlike some other makers’ switchable systems.

Key to the system was of course the dampers themselves, which were designed to be physically interchangeable with the non-CATS parts so that the same suspension componentry could be used.

Alongside these, the CATS system comprised an electronic control module located in the boot next to the battery, plus the crucial accelerometers. Designed to measure vehicle movement in three dimensions, two vertical sensors were fitted – one on the front bulkhead and one in the boot under the fuel tank – and a single lateral movement sensor. Acceleration and deceleration forces meanwhile could be calculated by the road speed and throttle position using the existing engine management electronics.

The accelerometers were actually simple devices, offering a varying voltage according to g-force: 05 volts at minimum, 2.5 volts at 0g and 5v at maximum.

Although the system was described as being continuously variable in its operation, in reality the CATs dampers have only two settings – firm or soft – and it’s simply the switching from one to the other which is done on the fly.

With the car stationary, the dampers are automatically switched to firm in order to minimise pitch under initial acceleration, reverting to the soft setting at speeds above 5mph.

Above this speed, the system becomes active, taking signals from the accelerometers in order to switch the units to the firm setting as required: cornering forces mean the system switch to firm, as does vertical movement indicating bumps or hollows in the road.

Similarly, as soon as the brake pedal is pressed the system will begin calculating deceleration and when braking forces exceed a certain limit, the dampers are switched to firm – again, to minimise pitch.

Outside of these conditions however, the system reverts to the soft setting in order to offer a respectable ride quality even on the 18-inch rims which had become popular by the time the XKR appeared. Interestingly though, if a fault is detected, the system revertesd to the firm setting rather than soft – apparently in the interests of safety.

As you can see, the system is a mixture of analogue voltage from the accelerometers and the digital element of the electronic control unit, but at the business end of the system it becomes decidedly analogue where the dampers themselves are concerned.

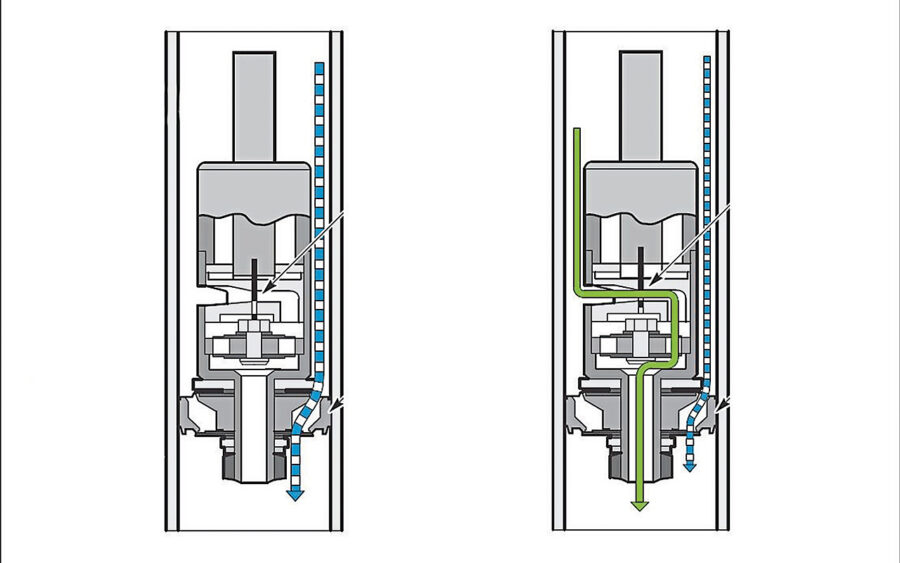

In operation a conventional telescopic shock absorber simply allows fluid to flow from one chamber to another, the orifices between the two determining the damping characteristics and it’s by varying the flow of fluid that an adaptive system works.

How this is achieved is in fact very simple: a solenoid inside the unit moves according to the voltage supplied via the electrical connection at the top of the damping rod to open and close an alternative fluid path inside the unit. With no voltage applied – such as when disconnected or in a fault condition – the fluid flows through the primary piston to offer firm damping. When the system is active and in soft mode, a bypass is opened which permits faster fluid flow and softer damping.

Back in 1996, this was clever stuff and to be fair it worked well, with road testers commenting favourably on the ride and handling of cars with Computer Active Technology Suspension. Interestingly, looking back through contemporary road tests, the system is rarely discussed in detail, suggesting that its unobtrusive operation was perfectly judged for the market.

The CATS system would be offered as standard on the supercharged XJR and XKR, as an option on the XK8 coupe, and on the XJ into the X350 generation when it was paired with air suspension to great effect.

The system would be continued into the X150 XK models, but would eventually lose its cheesy CATS naming in favour of the rather more serious Adaptive Dynamic Suspension but the basic principle remains the same.

Jaguar may not have been the first with an adaptive suspension system, but the number of cars out there still running on perfectly serviceable Computer Active Technology Suspension set-ups shows that its unobtrusive and relatively simple operation was perfect for the job. And if you doubt that, just find a BMW 8-Series owner, ask about the famously unreliable EDC set-up and watch the tears form…