We explore the inner workings of the V8-derived AJ-126 V6, first seen in the Jaguar F-Type

Words: Paul Wager Images: JLR, Paul Walton, Paul Wager

More years than I care to remember writing about classic cars have taught me one thing above all others: some of the best products from the British motor industry have come from the most unlikely places, usually a development team heavily stifled by resources. Examples include the original Range Rover, the collection of Metro bits which made up the MGF and the supposedly stop-gap facelift which gave the XJ-S a second wind.

Even by those standards though, the Jaguar AJ-126 engine is something of a curiosity: is it genius of the highest order or a desperately lazy short-cut? Maybe it’s a little of both and certainly JLR wasn’t the first to chop down a V8 engine to create a V6.

In this case though, it took a somewhat unorthodox approach which defied conventional logic in that instead of physically removing the redundant two cylinders from the casting, it simply lost the rearmost set of pistons, rods and valvegear and left the outer dimensions unchanged.

It’s a little more involved than that of course, but the AJ-126 engine remains a fascinating design which leaves you conflicted as you gradually realise what a great yet terrible idea it is.

The usual thinking behind moving from a straight-six to a V6 layout is that the more compact dimensions offer increased packaging freedom, as well as greater efficiency generated by the reduced internal friction. Clearly though, none of this is offered by the AJ-126 but on the other hand, retaining the V8’s outer dimensions meant the same engine mounts and packaging hardware could be used, immediately removing the need for costly bodyshell alterations to accommodate a new engine, plus the renewed crash testing.

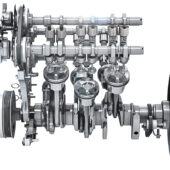

One result of the design is an unusually long crankshaft for a V6. Redundant journal is used as a balancing element

Additionally, retaining the longer block and crank of the V8 means a V6 engine with one more main bearing than is usual, all the better for refinement.

It’s a simplification to describe the engine as a V8 with two pistons missing, though and clearly if you take one of these units apart, you won’t find an empty bore and a strangely bare cylinder head. It’s a little more elegant than that, with the block casting looking all but identical from the outside, yet carrying extra stiffening ribs where the rearmost cylinders would be.

The remaining bores are also reduced in size to 84.5mm, which with an 89mm stroke created the 3.0-litre capacity required by the marketing people.

Retaining the V8 block however also means the engine runs an angle of 90 degrees, whereas a shallower 60-degree angle is generally preferred for a V6 design in the interests of even firing intervals. Again, there’s good and bad inherent in this compromise, since the engine is marketed in supercharged form and that generous bank angle provides useful space for the bulky twin-screw supercharger.

Getting around the problem of uneven firing intervals is achieved by using a so-called split pin crankshaft which separates adjoining connecting rods so that each cylinder fires every 120 degrees of rotation.

With the covers removed, the area of empty bores can be seen

As for the crankshaft itself, it may not be identical to that in the V8 engine but obviously had to retain its length and run in the five main bearings of the block casting – good for refinement but not so good for friction. Once again though, this was turned into an opportunity by using the spare lobe to carry counterbalancing weight. Additionally, a balancer shaft is used to drive the oil pump, while a ribbed sump element reinforces the block to aid rigidity.

The engine is topped off with a pair of heads which are physically shorter than those of the V8, leaving the redundant casting area visible at the rear. On a bare engine this is amusingly obvious but installed in a car with the plastic coverings and pipework concealing the area it’s usefully hidden. Naturally, the four-valve, quad-cam layout is retained.

So, a slightly unusual approach from JLR to creating a modular engine family, but as we’ve commented, an idea tinged with both madness and genius simultaneously.

The proof of course is on the road and despite the criticism the unit may have received on purely theoretical engineering grounds, road testers have generally been unanimously positive.

The supercharged 3.0-litre has always been one of our favourite powerplants and many’s the time we’ve felt it was a better solution for a road car than the fiery V8 which can often feel like overload in everyday use. Indeed, our own Ray Ingman – who was an on-track instructor at the F-Type launch – remembers the V6 car being chosen for track work simply because it was easier to tame.

The ultimate evolution of the AJ-126 was found in the limited-edition F-Type 400 Sport

However the complexities of the firing order and crankshaft design, to the layman’s ear the V6 has a lovely hard-edged sound under load and in many ways its scream under full throttle gives it more of a modern high-performance engine than the bassy V8 – more Honda VTEC than TVR, if you like.

First seen in the F-Type in 2012, the engine would later appear in the XJ, XF, XE and F-Pace as well as Range Rover and Discovery, but was destined for a short production life. By 2019 it had been replaced in Jaguar models by the new turbocharged Ingenium straight-six and by 2020 the Land Rover products had gone the same way.

It remains a fascinating diversion in the Jaguar story and perfectly illustrates the British motor industry’s knack of extracting greatness from the most unlikely beginnings.