Handmade in late 1960, this preproduction E-type – registration 9600 HP – played an important role in the car’s development and launch

Words: Paul Walton

As the oldest example of the E-type, this Gunmetal Grey fixedhead coupe is as important to British culture as an original edition of William Shakespeare’s First Folio, John Constable’s The Hay Wain or a 1962 pressing of Love Me Do, The Beatle’s debut single.

All early E-types define the Swinging Sixties and this one more than most, it being the oldest. A preproduction example, it was also the manifestation of Jaguar’s growing confidence as a car manufacturer that, following five victories of the Le Mans 24 Hours between 1951 and 1957, validated the company’s position as one of the world’s greatest sports car manufacturers, up there with Aston Martin and Ferrari.

The car’s history, though, unlike The Hay Wain, is best described as rocky. It is only still here to be enjoyed thanks to a little luck and the foresight of several owners.

One of these is Philip Porter. In 1977, when this author, marque historian and E-type Club founder bought the car (universally known by its numberplate, 9600 HP), it looked no better than scrap, a reflection of its age and hard life. Philip understood the importance of the car’s place in history so, because he did not have the funds to restore it, he put it away for two decades in an open-fronted Dutch barn.

“Anyone driving or walking past could just look in at everything. Actually, it looked like a local scrapyard.” That’s how Philip describes the car’s condition in his recent book about it – 9600 HP The Story of the World’s Oldest E-type. “Also, the weather could get in, which was not good, but everything had to be a long-term plan and could only progress as I could afford it. No one believed I would ever do anything to the poor old cars, including 9600 HP, which looked sadder and sadder as the grime built up.”

The situation was a long way from the car’s heyday in the early Sixties, when it had a pivotal part in the development, and later debut, of this now-iconic sports car.

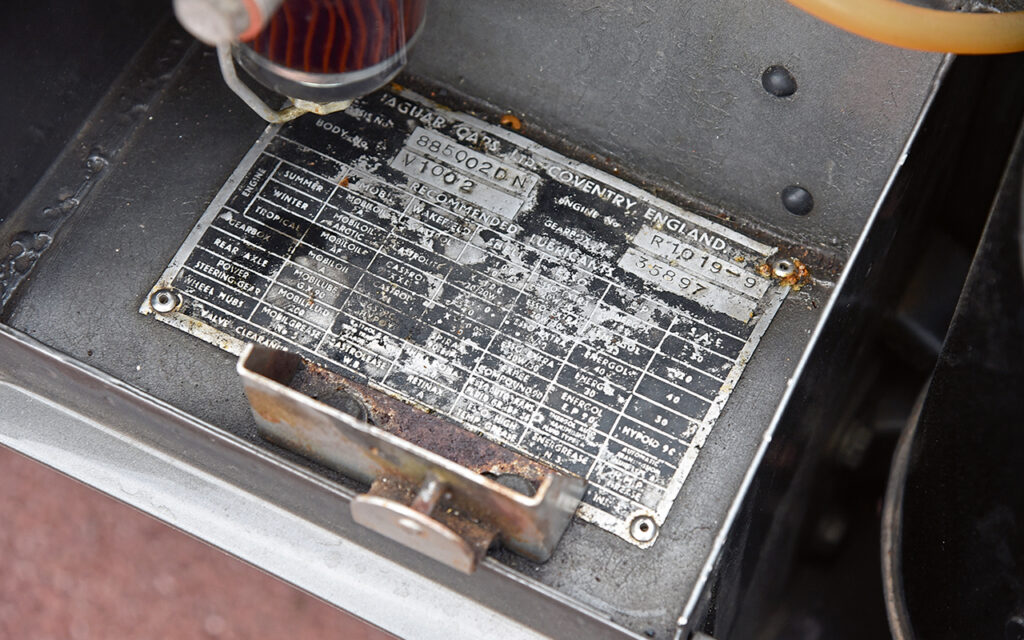

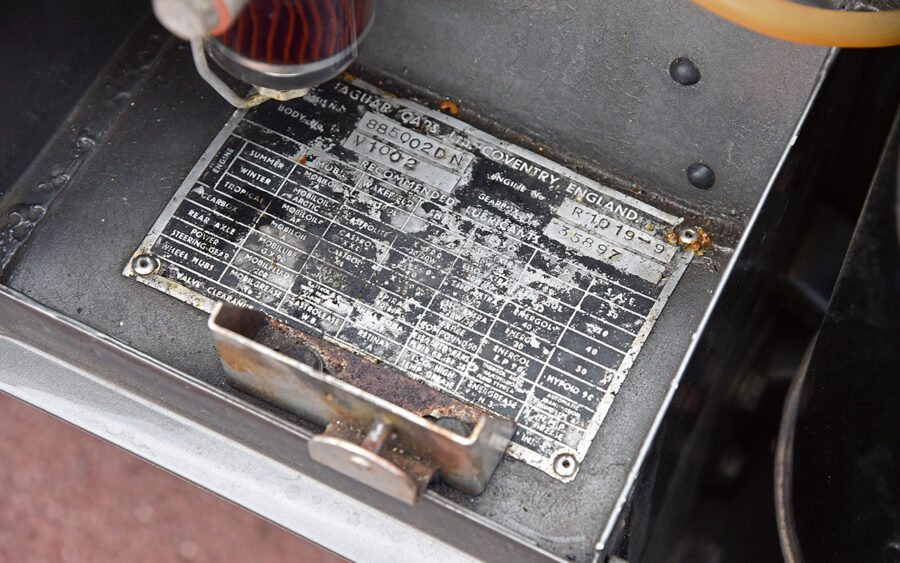

It’s not exactly known when 9600 HP was built, but as the seventh E-type prototype, it was probably autumn 1960. It followed production of the pale green E1A you’ve just read about, a grey roadster (christened the Pop Rivet Special due to its construction), an unpainted steel body, two roadsters (blue and red), and the first fixedhead coupe.

While Malcolm Sayer takes overall credit for designing the E-type, the closed car was actually the work of Jaguar’s famed metalworker, the skilful Bob Blake. He used steel rods to shape a profile of the roof – which flowed elegantly to the tail – plus a side elevation of the screen.

“The Old Man [Sir William Lyons] looked at it and, boy, he liked it,” Blake says in Jaguar E-type The Definitive History. “He fell in love with it the minute he walked in the shop. He wouldn’t say a word. He put his hand to his mouth, the way he did. He just walked round and round it and looked at it from this way and that way and the front. He said to me, ‘Did you make this Blake?’ I said ‘Yep’. ‘It’s good. We’ll make that.’ And we did.” Blake recalls that Sayer later corrected errors in his design and perfected the shape.

We know from his logs that Jaguar’s test driver, Norman Dewis, inspected the second FHC (which started as left-hand drive) on 11 November 1960, drawing up a comprehensive list of items that needed attending to on the 22nd, before going to the MIRA proving ground two days later to give the car its first proper test. He bed the brakes in on the 24th, recording that, by then, the second FHC had covered 194 miles.

By the end of the year, the car became a common sight around the factory as it was being used extensively for testing. “I came into contact with it not much earlier than the beginning of ’61,” said Jaguar’s legendary PR boss, Bob Berry, in The World’s Oldest E-type. “Obviously, I had seen it around, as experimental were using it as a development car.”

Testing continued throughout winter 1960 and into 1961, including for maximum speed runs on the M1 motorway on 22 January when, according to Norman’s diary, he reached 143mph (the 70mph national speed limit wasn’t introduced until 1965).

“We used to use the M1 for doing the maximum speed test,” he said in The World’s Oldest E-type. “Very often, we would be doing 150mph, and other cars were there as well doing very high speeds, Aston Martin and other firms. It was a very useful place to do maximum speeds.”

More high-speed testing followed the next day, at MIRA, when the car was ‘only’ able to reach 142mph. This was a concern because the E-type was to be marketed as a 150mph sports car. So, to increase speed, Sayer suggested removing the front bumpers and adjusting the front suspension to a nose-down stance. Even more astoundingly, he proposed a fin similar to the long-nose D-type’s. Not long after, Jaguar fitted an experimental engine, E5020-0, to perhaps solve the problem.

The car was finally registered on Friday, 10 February 1961, when it was designated as a press car, which was the responsibility of Jaguar’s Pat Smart. He explained in The World’s Oldest E-type how it came to have such a memorable numberplate: “I’d say, ‘What’s the next nice number?’ and they’d show me a sheet. We used to try and get double zeros; 9600 HP just happened to be the next round number, there’s nothing more mystical than that.”

It was delivered to Maurice Smith at Autocar magazine for one of two prelaunch tests, the other being carried out for Motor using an early green convertible registered 77RW. Because the E-type was known to reach 150mph, that’s exactly what Smith intended to achieve, travelling to Belgium for the long, straight section of motorway between Antwerp and Herentals. “It was relatively easy to wind up to 145mph in under a minute, but the extra 5mph took a long time to show,” said Smith in a 1982 Autocar article marking the 21st anniversary of the drive. To get to 150mph he had to approach the straight at not less than 135mph, when, even at these speeds, he found the car to be stable. “In these days of air dams and wings, it seems surprising that the long curving nose did not lift and make the front end too light, or the short tail allow the car to wander.” According to Smith’s report of his test, which wouldn’t appear until the 24 March 1961 issue, he got the car up to 151.7mph, and achieved a mean speed of 150.4mph.

With only a few weeks before the E-type’s planned launch at the Geneva Motor Show on 16 March, where 9600 HP would have a starring role, work on the car became more frantic. Another engine (possibly its original) was fitted by early March and a performance test soon after showed it was slightly slower than the previous experimental unit. Bob Berry – who had been a successful amateur racing driver – was given the task of driving 9600 HP to Geneva where, on 15 March, Jaguar’s stunning new sports car would be revealed to the world. But the car was only passed off on the 14th, the day of his departure, leaving Berry to use all the E-type’s full potential on the M1 when he left Browns Lane at 7pm to catch a midnight ferry from Dover. The M25 was still 20 years in the future and he had to negotiate the centre of London, too, finally arriving at Dover four-and-a-half hours later.

After docking at Calais, Berry drove like a madman, passing through several French towns, including Arras, Cambrai, St Quentin, Reims, Châlons-Sur-Marne, Vitry, Chaumont, Dijon and Chalon-Sur-Saône. From there, he cut across to Tournus, Bourg, Nantua and into Geneva.

“My chief recollection was the very poor weather,” he says in The World’s Oldest E-type. “It was quite foggy. In fact, it was very foggy, from leaving the port as far as Reims. I remember arriving in the centre of Reims in that huge square and really not being certain where the hell I was. It was as bad as that.”

Thankfully, the conditions improved, allowing him to drive flat out. “I was so far behind schedule as not to be possible. But, on the basis that if you don’t try you’re not going to achieve it; I simply drove it as if it was a race. It’s the only description I can give you. I drove it flat out between the corners and all that sort of thing.”

In his quest to reach Geneva on time, Berry admits to occasionally reaching 140mph, “Youth often makes you do things that you wouldn’t have done normally.”

Despite just a bag of apples and two pints of milk for sustenance, Berry was successful; stopping only for fuel, he reached Geneva 20 minutes before the car was due to be revealed. The E-type was cleaned and prepared at Jaguar’s distributor for the French-speaking part of Switzerland, Marcel Fleury, then driven directly to the Parc des Eaux Vives, where the motoring press gathered for a Society of Motor Manufacturers event. “Good god, Berry,” said Sir William Lyons on Bob’s arrival, “I thought you weren’t going to get here.” Yet, despite the length and stress of the journey, Berry enjoyed the drive: “It was the most incredible journey, and I’ve never forgotten it.”

The E-type had another role during the show, which was to give passenger rides, driven by Berry, around a test circuit to the south side of Geneva’s Lac Léman. When Berry couldn’t keep up with demand, Norman Dewis was instructed to “drop everything” and bring the green open two-seater 77RW, which was still in the process of being prepared for its drive over the following week. Norman received the call at MIRA, went home to pack a bag, then, like Berry, drove through the night to reach Geneva by the following morning.

These former racers didn’t hang about on the circuit of closed public roads, which included a hill climb section, either. “There was a bit of a contest between Dewis and me to see who could get up fastest,” said Berry.

The cars remained reliable, despite taking “an awful hammering” according to Dewis. “I don’t think we put a spanner on either of them during the entire period,” he said in The World’s Famous E-type.

For ten days, the two cars proved quicker than their Ferrari and Mercedes opposition.

“I don’t know who started it,” a bright-eyed Norman told me in 2001 as he remembered the event, “but unbeknown to Bob and I, some bright clown decided to get a stopwatch. He comes over (I think he was a Swiss bloke) and said, ‘Le Jaguar is very queek – you are the queeckest up the hill.’ The Mercedes drivers heard about it, as did Ferrari, and they all tried to go quicker all day, every day. But the Jaguars were always the fastest, though that wasn’t intended. It came out of the blue.”

He recalled how he and Bob had scared their passengers. “Some of these poor souls had never been in a sports car; their knuckles were white and their toes were back, right back out of fright, especially when we went past the breaking point of the Mercedes drivers with their drum brakes. I could see them thinking, ‘The car isn’t going to make it,’ then I’d bang the brakes on. Nobody could believe the car could stop so quickly then accelerate so fast.”

If there is any one particular moment that the E-type legend started, it was there, with 9600 HP and 77RW chasing around Lac Léman during those heady days of March 1961.

After the excitement of Geneva, it was back to work for 9600 HP. “The clamour to borrow the car was enormous,” said Berry; as well as other British publications, it appeared in the Italian, German and French press.

Development work followed later in the summer when Dewis took it to Bayonne on the west coast of France to compare production dampers with oil separation dampers. It was around this time that it was converted to right-hand drive.

However, its time with Jaguar was coming to an end. Unlike the six earlier prototypes that were scrapped, on 4 May 1962, the renowned Jaguar dealer, Coombs of Guildford, bought 9600 HP, before passing it on to a leading British film director, John Carstairs, who kept it for three years.

The next keeper was no stranger to fast Jaguars. Jack Fairman had raced C-types and D-types during the Fifties, and was also behind the speed and distance record attempts in XK 120s at L’autodrome de Linas-Montlhéry, near Paris, in 1950 and 1952. After buying the car in June 1965, Fairman sold it three years later to a Pease Pottage-based sports car specialist, Richardsons. From there, and then almost a decade old, 9600 HP passed to David Lockhart Smith, who lived outside Brighton. The E-type needed some remedial work to pass the MOT test, including a new clutch, brake parts and several seals. David and his son, Peter, used the car hard, driving it up to the Lake District while house hunting, as well as to Monte Carlo for the Grand Prix.

It was put in storage for a year following the Lockhart Smith’s move north, after which the engine wouldn’t hold water and overheated. Consequently, between 1971 and 1975 it was barely used. With David Lockhart Smith becoming ill, and the car needing to be restored, he sold 9600 HP in January 1976 to what’s thought to be a Manchester-based dealer because it was soon sold on again, this time to Derek Brant, who had travelled from London to the North West after seeing an advertisement for it in The Sunday Times. As well as buying 9600 HP, Brant also bought the first production right-hand drive coupe (1 VHP) the next day, and the 12th roadster (848 CRY, which had appeared in The Italian Job) a few months later. He also later acquired the 232nd E-type OTS.

Brant initially kept 9600 HP on the road – the car passing its MOT test on 12 December 1976, when it had 50,988 miles on the clock – but he knew it needed rebuilding. Unable to do it himself, he came up with a novel idea after reading an article in the June 1976 issue of Thoroughbred & Classic Cars by journalist Paul Skilleter (who would later found JW’s predecessor, Jaguar Quarterly, in 1988), announcing that the magazine was looking to buy an E-type. Brant suggested to Paul that the magazine borrow one his cars, and they perhaps become partners in its restoration. While that didn’t come to pass because the magazine had already found one, the two remained in contact, and Paul later photographed 9600 HP at Brant’s local garage.

Brant had been planning to keep the four E-types as an investment to eventually help pay off his mortgage, but, during a Spanish holiday in January 1977, he had a religious experience while praying in church.

He said to Philip Porter for The World’s Oldest E-type, “I really felt God speak to me about selling these cars, ‘They are a millstone around your neck’. I hadn’t seen that. There was almost a debate going on, as happens when you are praying, trying to hear what God is saying. I said. ‘No, these are for my family.’ He said, ‘It’s not my plan for you. I have other plans for you.’”

On his return to the UK, he asked Paul Skilleter for help in selling the E-types, who in turn called his friend and fellow Jaguar enthusiast, Philip Porter. Despite some misgivings from his parents, Philip bought the quartet for a considerable £5,200.

The 232nd roadster sold quickly, but the rest – requiring significant work that he could not afford, 9600 HP especially – were kept. “I knew that one wrong move with 9600 HP could prove fatal. For this reason, and because of the staggering cost of doing this car justice, I sat on 9600 HP for over 20 years.”

The first to be restored, it being in the best condition, was 848 CRY in the late Eighties. A decade later, Philip finally turned his attention to 9600 HP. Bridgnorth-based specialist Classic Motor Cars (CMC) agreed to put the seventh prototype back onto the road in return for buying 1 VHP (the first production right-hand-drive coupe) for one pound. “Although I was a little sad to think of losing number one, it was a patently fair deal from my point of view.”

It was a Herculean task to keep as much of the car as original as possible, and, between April 1999 and March 2000, the restoration notched up some 3,500 hours. It revealed some crude craftsmanship beneath the surface due to changes during the car’s development, including rough holes in the bulkhead for the pedals when it was converted to right-hand drive. All of these anomalies were kept.

Two decades later, Philip still owns the car. He is unafraid to use this automotive icon, so 9600 HP is a regular sight at classic events throughout the year. “I’m just a custodian until the next generation,” he tells me.

It’s a significant piece of British history, so when he invites me for a drive it feels on a par to being allowed to hang The Hay Wain in my living room. I admit to getting goosebumps when he slowly rolls it out of the garage. Resplendent in Gunmetal Grey, the two decades-old restoration still looks good, while its almost constant use has created an authentic patina. I wonder if this is how it might have appeared when Bob Berry hurtled down to Geneva 60 years ago.

I can imagine you’re thinking I now feel as cool as George Harrison, who owned a similar FHC during the early days of The Beatles. But a coupe, with its low roof, high and wide sill, plus large steering wheel, is incredibly tight and I feel more like George Formby as I climb awkwardly inside.

It’s worth the struggle, though. I get the same thrill with 9600 HP as I did when I drove 77RW earlier in the year and imagined Norman Dewis taking the car to Geneva; Bob Berry sat in this very seat, looking through this very screen and holding this very steering wheel. As someone who’s passionate about Jaguars and their history, it doesn’t get much better than this.

This being the earliest of early E-types, the interior is the classic layout of a row of four white-on-black dials with a line of six flicker switches beneath, all laid into an aluminium centre console, and with two huge dials directly in front of me. Who needs to be able to stretch out when interiors look this good?

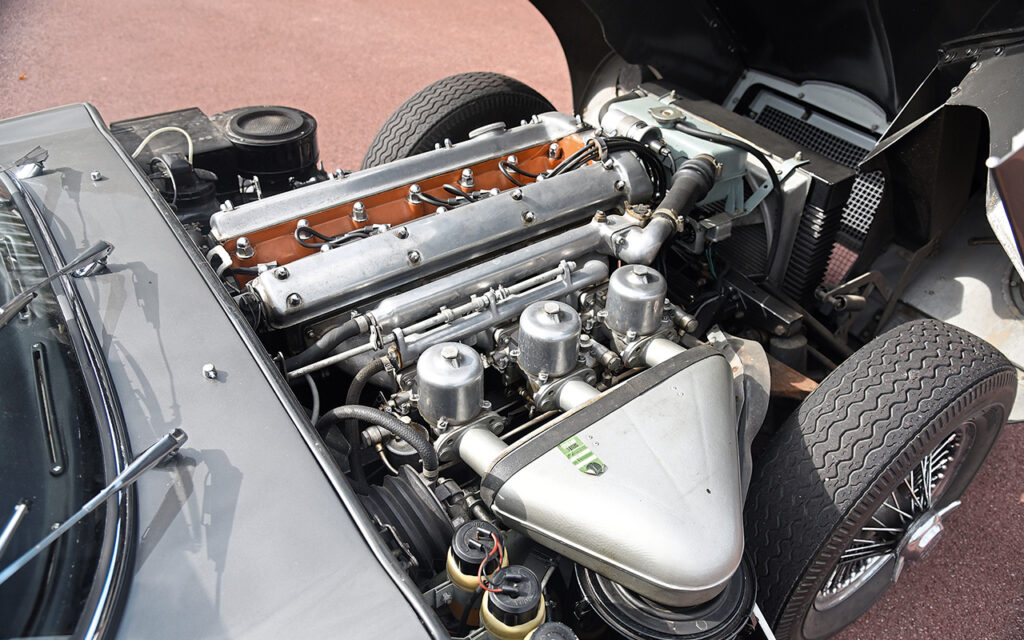

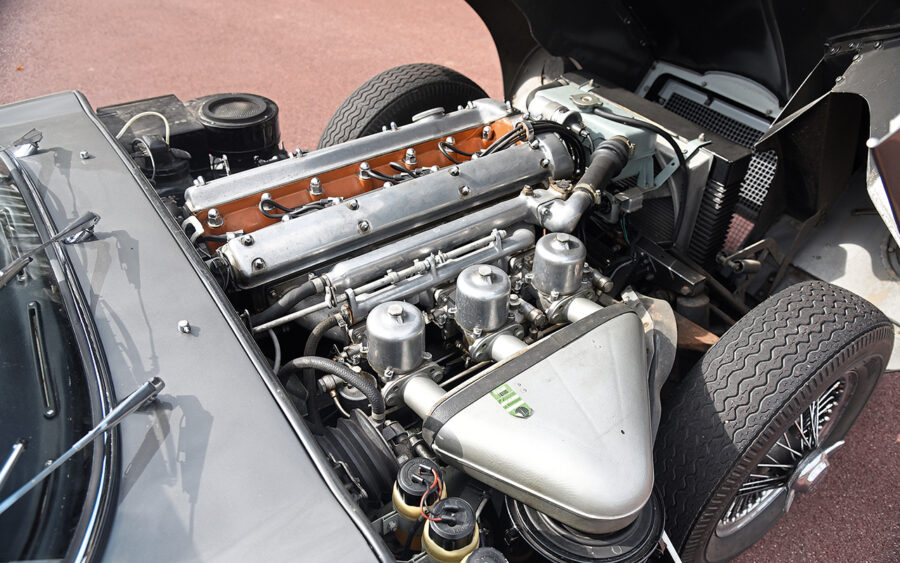

The 3.8-litre engine roars instantly into life as I touch the starter button and, after snicking the four-speed ’box into first, the car moves easily and smoothly forward. Philip admits to fitting some “hotter cams” during its restoration and its acceleration is instant and gutsy, more so than a standard E-type 3.8. The XK unit sounds terrific when pressed hard, a deep, satisfying, meaty growl that fills the cabin.

The engine’s strong torque means there’s no need to change down for an oncoming corner, the old unit having enough strength to accelerate out in a high gear – and that’s a good thing. The Moss ’box lacks synchromesh on first and second, and grating the gears of this famous car would be as awkward and uncomfortable as dropping Constable’s masterpiece.

With sharp and accurate steering, plus almost zero body roll, I’m able to slice cleanly and quickly through bends before nailing the throttle, the car as eager to put down its power as my tiny terrier is to bolt through the front door and yap at the postman.

While this is truly a real honour and an experience I will never forget, strip away the car’s importance and, much as Love Me Do is just a brilliant pop song or The Hay Wain a beautiful landscape painting, 9600 HP is, at heart, simply one of the best-handling sports cars of the 60s. It just happens to also be the start of a legend.