Former Jaguar designer Nick Hull takes an inside look at the development of the controversial S-Type courtesy of the development meeting minutes

Words: Nick Hull Images: Jaguar World

The S-Type of 1963 is a good example of Sir William Lyons’ knack of extracting as much value as possible from an existing bodyshell. Based on the MkII shell, it provided Jaguar with an intermediate model that bridged the gap between the compact MkII and the big MkX, not just in terms of size and price, but also in styling.

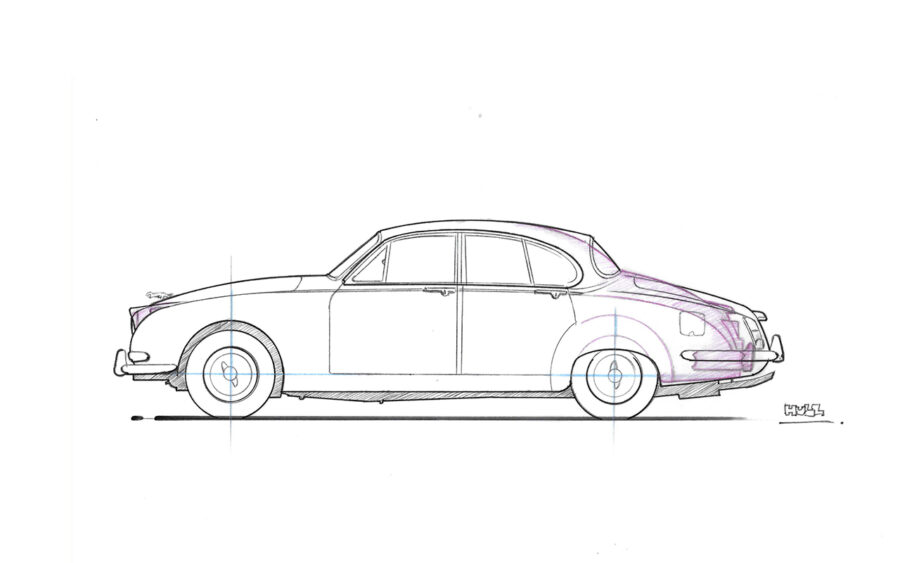

Code-named XJ3, or ‘Utah Mark III’, the S-Type retained the centre structure, bonnet panel and doors of the unitary Utah shell that had been developed for the compact MkI in 1955. Onto it was grafted a shapely Jaguar MkX-style tail adding 6in to the rear overhang and allowing space for the bulky IRS cage from the E-Type and twin fuel tanks in the rear wings.

Jaguar’s body engineers managed to subtly increase rear seat space within the same wheelbase in the S-Type by repositioning the seat cushion and inclining the seat backrest by 1 in. Headroom was retained by use of a thicker C-pillar and rear backlight set more vertically than the MkII, together with a longer, flatter roof.

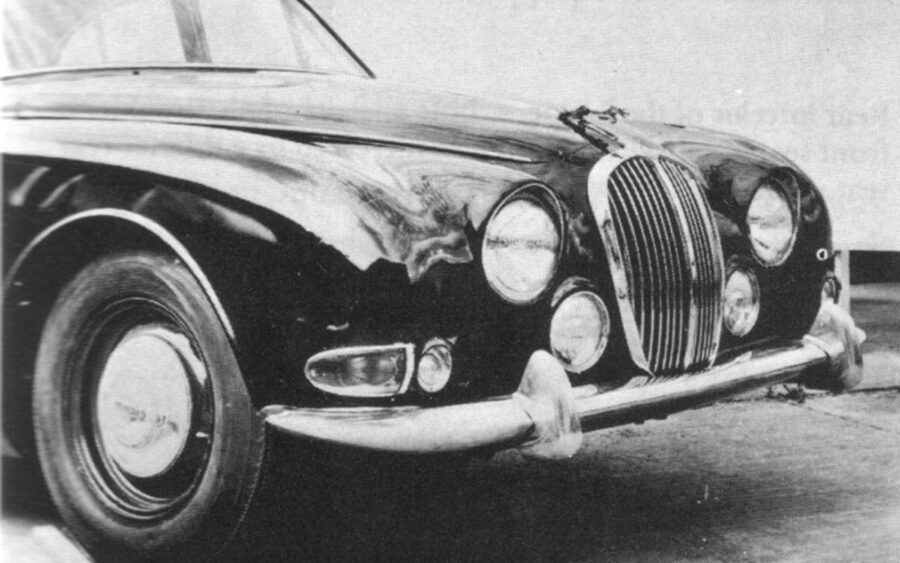

The front end of the S-Type was cleaned up and modernised with slimline bumpers, recessed foglamps and wrapround indicators, while the headlamps gained the same hooded treatment as the MkX.

Research into Sir William’s archive at JDHT reveals that the initial body styling mock-up of XJ3 had been developed during the spring of 1962, roughly concurrent with Sir William’s main preoccupation during this period – the emerging XJ6. The archive contains a memo dated 24 May 1962 from chief body engineer Bill Thornton confirming that ‘the Mark III mock-up has been dispatched to Pressed Steel Company in Oxford on Monday 14 May’ and that ‘PS Co. have been informed that the new front end change is to be held and introduced together with the new rear end and roof for production in July 1963’. The memo also details that Pressed Steel had previously supplied cost estimates for the body changes back in January of that year – presumably based on initial body drawings, rather than the styling mock-up.

It also outlines a rather homespun proposal for a simpler roof modification where the existing MkII roof pressing would be simply flattened by 3/4in in the centre using the existing secondary operation tools for the screen, with a carry-over rear window aperture.

Interestingly, Lyons wanted XJ3 to have a four-lamp front end as on the MkX but was advised that it could not be achieved in the time available. In the end XJ3 got the hooded lamps look, but only as a modification on the existing two lamps. Lyons did eventually get his desired four-lamp front end of course, but not until the 420 in 1966.

It also appears the chrome upper door frames were initially planned to be shorter to suit the flatter roofline – a bit like the Rover P5 Coupé. Pressed Steel supplied a second estimate to modify the roof with the cant rail lowered by approximately 1/2in at the B-post but this was later rejected as being too costly. The Thornton memo confirms that ‘The final roof as per the mock-up has a completely new backlight, slightly longer at the rear deck line’ – so necessarily the roof pressing would be all-new but the doors would remain carry-over.

Bob Knight was given the task of managing XJ3 into production, and research into his papers from 1963 give us a fascinating insight into the way a vehicle project at Jaguar was run at the time, with a series of 18 progress reports from January to October 1963 detailing the development of the project.

These Engineering Report Minutes from the 1960s follow a strict format that was maintained up to the 1990s. Typically they start with a short update summary, followed by 6-7 pages detailing every outstanding issue to be discussed. Set out in columns are the Item Number, Engineering Release Dates for Styling, initial design, prototype, test, final design, followed by Tooling – split into those items being manufactured by Jaguar and ‘Bought Out Items’ made by suppliers.

Remarks for each item and action points by name are listed. As an early form of monitoring project timing, they were an important step forwards at the time and a valuable source of precise information to historians today.

Almost no photos exist of XJ3 in development. This image is believed to show the initial mock-up from spring 1962, which would have used an existing bodyshell with hand formed parts added directly in sheet steel. Note the missing front wheel, the straight bumper and different overriders being tried out

2 January 1963

At this first XJ3 progress meeting the basic timing and drawing office schedule for engineering design and development work was presented, complete with hand-drawn timing plans on graph paper and neatly coloured blocks in crayon to indicate the timing for each engineering section: body, chassis, electrical and engine.

Two prototype cars would be built by Experimental at Browns Lane. The major issue at this meeting was the concern that Pressed Steel was quoting delivery for the first pre-production bodies as August 15, with series production bodies only scheduled from December onwards – far too late for a motor show launch that autumn.

By today’s standards it seems astonishing that such a major programme, encompassing heavily revised body and rear chassis, new rear suspension and new interior, might be attempted for a launch planned just ten months later, with such a tiny number of staff assigned to the programme.

30 January

Urgent discussions with Pressed Steel had resulted in a speeding-up of initial body supply, with the first off-tools body now scheduled for July 12. The grille surround and centre bar would now be produced as a die casting rather than a pressing, but timing was critical. The rear seat frame would be a carry-over part from the MkII but the seat squab frame would be new. Progress on new IRS parts and mountings was proceeding as planned, as were drawings for electrical items.

18 February

Number 1 prototype body was now painted in the Experimental Department and should be completed for testing by April 1. The first two off-tools bodies were now scheduled for June 28, with four more due by mid-July. The decision was taken to produce a third prototype for styling verification purposes. The bootlid emblem showing ‘MkIII’ was cleared for manufacture.

Rear view of same mock-up model. Lucas tail lamps were shared with the MkX

15 March

Number one prototype build was proceeding and number two body was painted. Number three body was awaiting parts from Pressed Steel with some contingency parts being supplied by Abbey Panels. Plans to use MkX headlamp bezels were dropped – new items would be required but Lucas required 6 ½ months for tooling…. By 22 March the radiator surround and grille drawings were issued, with parts to be made by Metal Castings Ltd, Worcester and the first samples scheduled for July.

1 April

Mr Knight reported favourably on his first run in number one prototype. It was agreed that prototype cars would be camouflaged for road trials. The XDM2 front seat frame was to be slightly modified and commonised for use on Daimler and XJ3 models. The rear window glass would be slightly modified to introduce some small vertical curvature in it. By 5 April number three body was being built in Experimental.

3 May

Number two prototype was nearly complete. Pressed Steel reported that since inner rear wing extension panels could not be produced before November, hand-formed panels would be used until then. On May 8 Bob Knight reported that car number two will be ready to run on May 10. One item causing problems was the toolkit container – the MkII item was deemed too heavy and a new part was needed.

31 May

Testing of number one and number two protypes was under way, while number three body was in progress. All woodwork drawings were complete. All facia, console and heater parts had been designed – 33 parts in all – but all requirde approval by Sir William.

6 June

Number two prototype was now in a fully internally-trimmed condition, available for Sir William to approve.

25 June

Timing of the first six off-tools bodies was confirmed: two for June 28, two for July 5 and two for July 12. New zero-torque door latches by Wilmot Breeden were causing problems. Two possible systems for electric windows were being investigated: a Teleflex type by Lucas and a Wilmot Breeden system, as on MkX, but neither would be ready for initial launch.

Compared to the Mk2, the S-Type had a more upright rear backlight with the window base sat slightly lower to suit the line of the flatter roof

10 July

Bill Heynes was in favour of using Dunlop SP41 radial tyres on XJ3 but Knight wasn’t completely satisfied with the performance, therefore RS-5 tyres would be used, as per the original plan. Sir William was unhappy with increased costs quoted for front seat frames and roof sound deadening over MkII items.

16 August

Two pre-production cars were passed off the lines to test, with two more on the mounting track and two in paint. Some 25 woodwork sets had been completed, with 100 in progress in the wood mill.

13 September

Three publicity vehicles sent to Experimental had been released back to Publicity Dept: a 3.8-litre manual, a 3.8-litre automatic and a 3.4-litre. A total of seven cars were being prepared for Earls Court. Body number nine was selected for mileage and pavé testing.

27 September

Production was agreed at 20 cars a week for the week of September 27 and October 4, thereafter 50 cars a week. 110 cars were to be produced as a batch for release to Home Market dealers – two cars per dealer. ‘As many cars as possible would be subjected to a short 15 minute test duration by Experimental, probably Mr Knight himself…’

22 October

Final report. ‘It was agreed the fortnightly report on XJ3 would now come into the orbit of regular production meetings’.

The reports also cast a light on how the body quality was improved. On October 2 Bill Thornton reported that when MkII production first started, the windshield aperture was consistently incorrect and Pressed Steel were given a concession to produce in this fashion. Consequently the windshield glass was modified away from drawings to suit. Amusingly it notes: ‘Now the XJ3 body windshield aperture is deemed correct to drawing and consequently the MkII screens do not fit correctly. Mr Thornton says he has the matter in hand’ [!]

To justify its position as a more sophisticated car than the MkII, the interior was heavily revised using more modern materials and updated seats. Of course, this was not the first time the MkII body and interior had been revised, with the XDM2 Daimler 2½-litre V8 saloon having been launched in October 1962, just prior to the XJ3 project. This featured a revised centre tunnel pressing and console and introduced a new reclining front seat frame with cushions that overlapped the tunnel. This same item was used for XJ3 but with new foams to give an impression of more cabin width.

Although the dashboard used the same instruments and basic switchgear, the design was improved over the MkII, with a new centre console and heater controls, and revised door cards. Vacuum servo-operated heater control valves were being used, as developed for the MkX, and these required more design and development than initially planned. A larger heater matrix was also employed for stronger heat output.

The dashboard followed the theme of the larger MkX where the instruments were recessed behind the veneer, which was given a nice radius into the switches and clocks. The curved padded centre console included a wide, open shelf above with the heater controls contained in a veneered roll – all far superior to the more functional MkII layout.

Despite the tight timescale, the interior of the XJ3 was one of the first instances of a more professional approach to packaging and design ergonomics within Jaguar. In 1962 an in-depth study of the rear seat had been undertaken during initial planning stages, with additional headroom and a more comfortable seating posture being found to be valuable gains as part of this exercise.

Much more shape was introduced into the rear seat squab to increase comfort and support during spirited driving and the door armrests were redesigned to offer a more ergonomic elbow rest angle than on the MkII. Knee room in the rear was increased by 3in by adopting the Daimler V8 front seat design with hollow frames and a Dunlop rubber diaphragm spring case and incorporated small individual armrests in the seat backs. The front seats also gained fully reclining seat backs as standard and extra fore-aft adjustment was gained by use of concentric tube seat runners, as introduced on the Daimler. Headroom was maximized using a new type of fibreglass sound deadening pad for the headlining.

Vehicle refinement was gained by use of the IRS and revised front spring rates. The project required development of a new IRS crossbridge suitable for its 54in (140 cm) rear track, coming as it did between the 58in (150 cm) track of the MkX and 50in track of the E-Type. The halfshafts were solid rather than tubular and the propshaft included the addition of an internal cardboard tube to dampen noise – a typical example of Knight’s attention to detail.

Apart from some unplanned strengthening plates to the rear chassis members, surprisingly few problems are mentioned in the minutes for incorporating this major item into the revised Utah bodyshell.

The XJ3 was launched as the S-Type at Earl’s Court in October 1963, in the same week as the Ford Corsair. Interestingly, the Corsair was a similar exercise to the S-Type – a re-skinned and extended version of the Mk1 Cortina, with larger engines, a repackaged rear seat and targeted at a higher market position than the donor car. The price was less than half that of the Jaguar however – £709 as opposed to £1669 for the S-Type 3.4 litre.

More pertinent to Jaguar was the announcement at Earls Court of two new models from Triumph and Rover, both titled ‘2000’ and both crisply styled models that would subsequently challenge the MkII in the coming years. The Triumph 2000 was a very rushed two-year programme by Leyland to replace the ageing Standard Vanguard and was all-new apart from its six-cylinder engine. The Rover was a more measured development that had taken a full five years to come to fruition and featured a new four-cylinder 2-litre engine. Priced at £1094 and £1264 respectively, these compact executive cars would appeal to a younger audience whose values were thoroughly modern as we entered the ‘white heat’ optimism of the 1960s.

By contrast, the S-Type was an amalgam of mid-1950s bodyshell, updated with late ’50s details, – the MkX exterior had been signed off in 1958 – so hardly a cutting-edge design by 1963. Having said that, it occupied a unique spot in the UK market with its powerful 3.4 and 3.8-litre XK engines, beautiful ride and excellent handling and was a far more desirable proposition than the cart-sprung Humber Super Snipe or Vanden Plas Princess 3-litre.

The P5 Rover 3-litre was probably the nearest direct rival to the S-Type at £1641 but that too had a live rear axle and moderate performance and its sober image was a polar opposite to the Jaguar. The Mercedes 220S was closer in specification, performance and flashiness but came in at a whopping £2280 after taxes – more than a MkX.

In all, the S-Type development had gone surprisingly well, given it was up against a punishing timescale. Bob Knight went on to lead the 420 programme in 1966, which completed some unfinished business with the S-Type aims and acted as a transition until the XJ6 was ready in 1968.