Hailed as the smoothest engine the automotive world had ever seen, the Jaguar V12 engine certainly proved to be a versatile unit

Words: Jim Patten

Exotic and unobtainable by mere mortals, the V12 engine was worshipped from afar. Steeped in mythical lore, these complex marvels were tended by a team of Latin maestros, the only engineers capable of orchestrating perfection. Until, that is, upstart engineers from Coventry dared to perform miracles and had the temerity to put a unit into production that was so smooth, nothing else could compete.

The Italians might have hijacked the V12 configuration for their fabulous sports cars, but the first application was British: Glaswegian Alistair (Arthur) Craig set up the Putney Motor Company in London and proceeded to build a side-valve V12 engine of 18.3-litres, producing 155bhp, designed for powerboat racing; Packard beat Sunbeam to the post in 1915 for the first V12 engine in a production car. Other American companies followed, with Lincoln being especially successful.

A tenuous Jaguar link joined the fray in 1927 when Daimler designed the incredible 7.1-litre sleeve-valved V12. Rolls-Royce followed with its Phantom, then Lagonda with its WO Bentley-designed unit. Ferrari and Lamborghini elevated the format to supercar status. The one thing that they all had in common was exclusivity and low production runs – but that was about to change.

By 1955, Jaguar’s legendary XK engine had been around for seven years, and it was evident that a replacement was due in the future. In fact, it would survive in many forms through to 1992.

Still at the sharp end of racing (principally Le Mans), Jaguar’s engineers realised that the stalwart six-cylinder twin overhead camshaft unit was already being outclassed by lighter and more powerful units, especially Ferrari’s V12, a format that the Italian outfit had been using since 1947.

Riding high on the successes wrought at Le Mans, and the subsequent increase in showroom sales, all ideas were considered. A V8 configuration was rejected for several reasons: it would need intensive crankshaft work to achieve the right balance and the bank-to-bank firing sequences were too limiting; plus, consideration was given to the all-important American market where the V8 was already the dominant force, and for Jaguar to go down that route it would need to be different. A V12 Jaguar would certainly have an exotic edge over the homebrew V8s, and became the favoured option.

In his superb booklet on the V12 engine, Walter Hassan set out four design parameters:

1) To develop, in production form, similar power to the best achieved by the XK engine in racing trim. A gross output figure of around 330bhp

2) To achieve this with minimum increase in installation weight (final increase was 80lb)

3) To keep cost increase as low as possible

4) To fit into the same space as the six-cylinder engine without structural alterations to the body hull of existing models

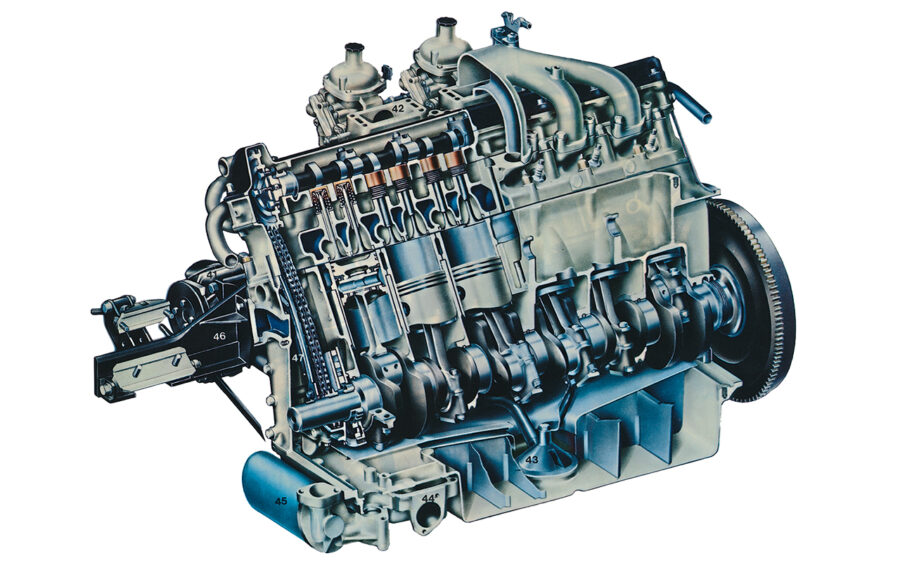

Hassan further stated that the last factor was largely responsible for the adoption of a single camshaft per bank, the design that finally made it into production.

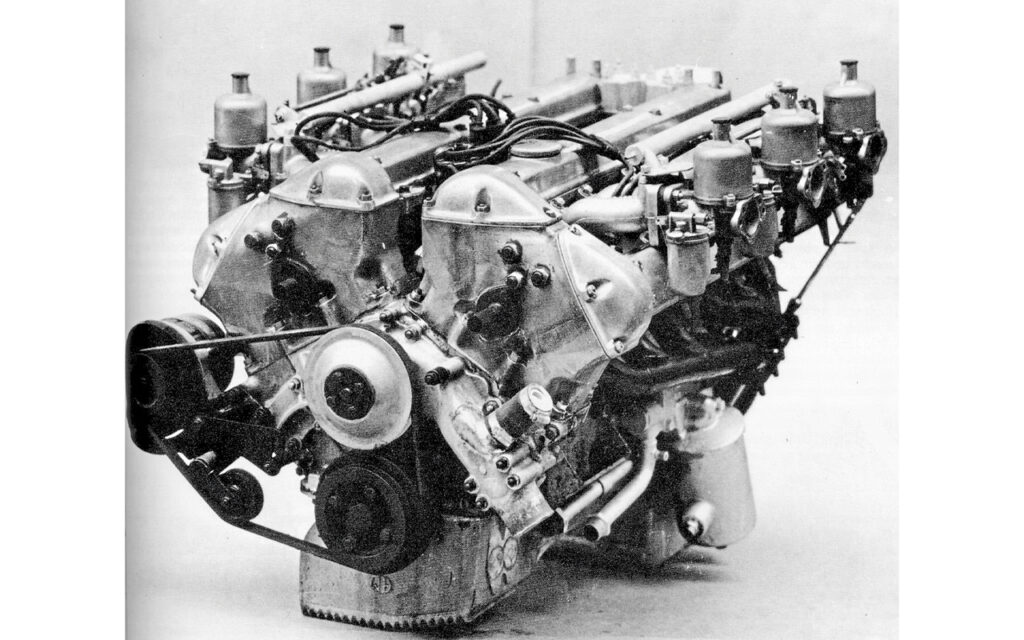

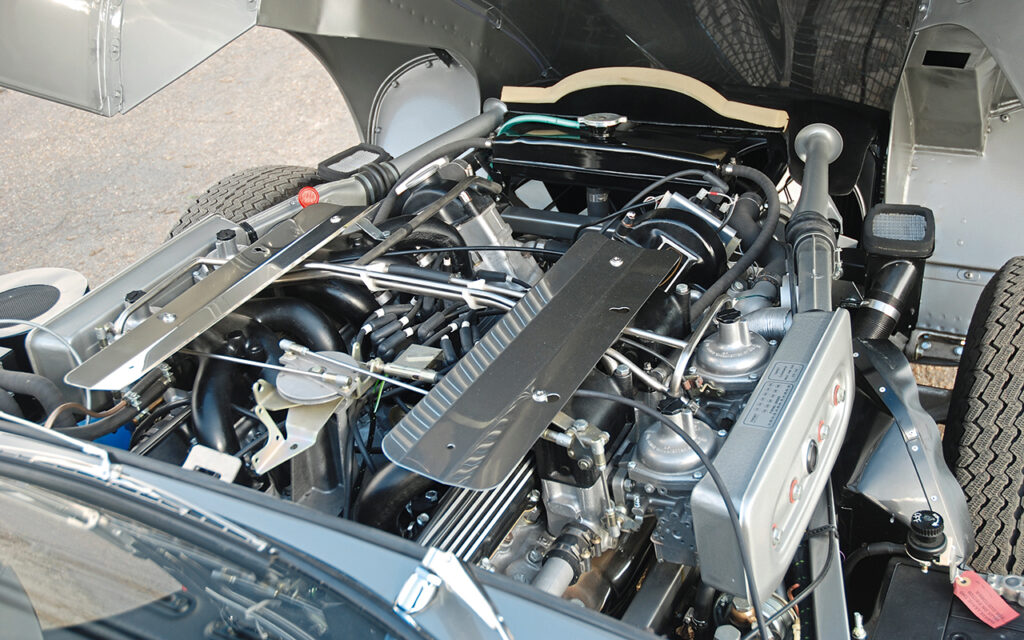

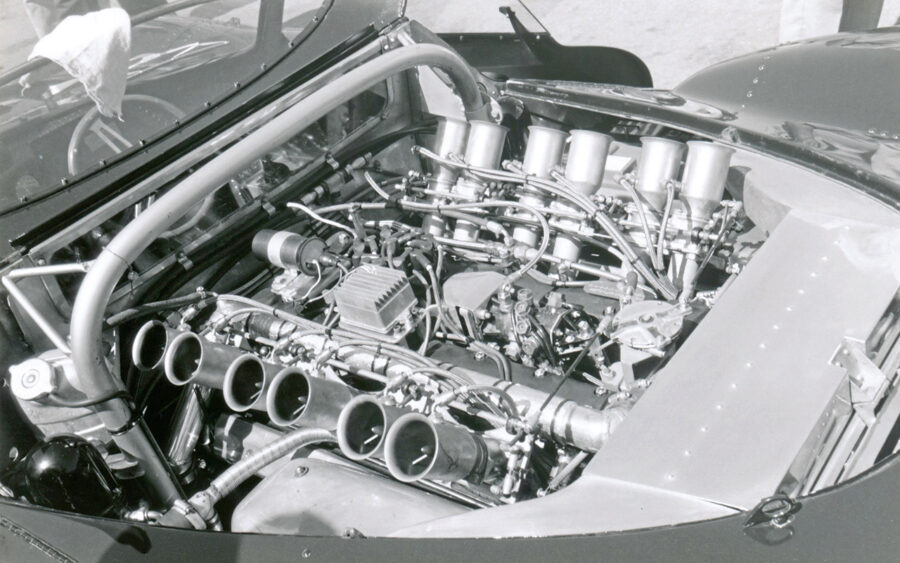

With a second planned assault on Le Mans, work began (almost in secret) on a mid-engine prototype racer that would eventually evolve into the unique XJ13. A change in regulations allowed Jaguar to exploit a capacity of 5.0-litres, and, with a bore and stroke of 87mm x 70mm, the new engine made 4,991cc. Ironically, the internal experimental code was XJ6, a term later adopted for its six-cylinder saloon car. The sand-cast engine block was fitted with slip-fit cast iron liners. At this stage, two banks of twin overhead camshafts were to be used, following the XK engine design principle, and both production and race engines were planned. In race tune, initial power output was 502bhp.

It is thought that fewer than ten quad-cam engines were constructed, but just a single example of the XJ13 race car. A Mk X was adopted as a road test mule in 1965, where the V12 engine (code XJ6/2) was altered for road use. The dry-sump system was abandoned in favour of a larger, wet-sump one, while duplex timing chains were harnessed to drive the camshafts, rather than the geared arrangement on the race engine. No fewer than six HS6 carburettors supplied the fuelling.

Never a fan of the Mk X, legendary journalist Denis ‘Jenks’ Jenkinson was given an example to drive back to the Jaguar factory while his own E-type was being attended to. Nobody told him he would be driving the mule, and he could hardly contain his excitement.

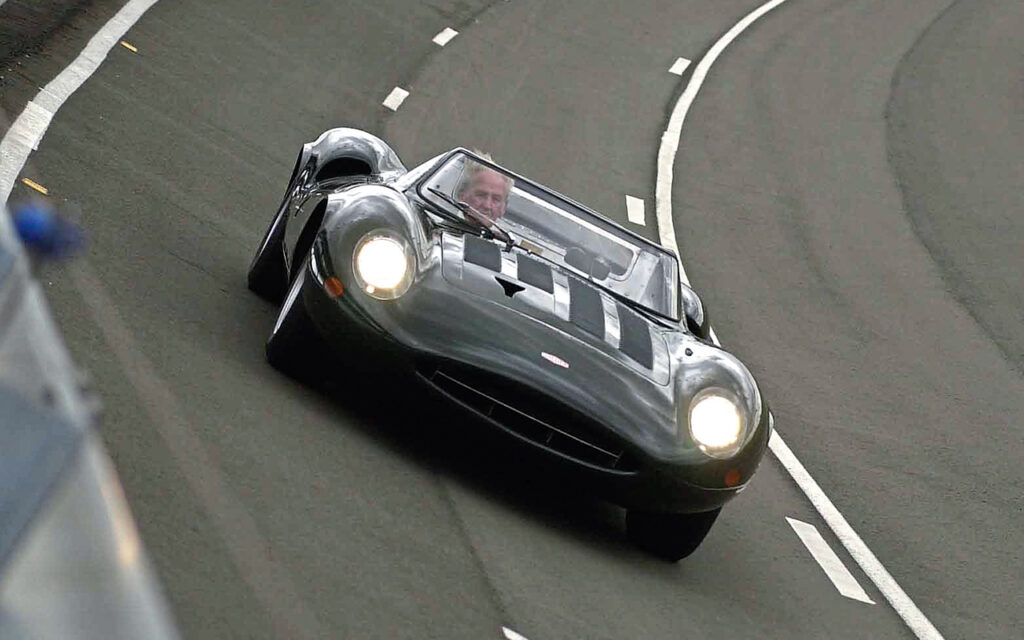

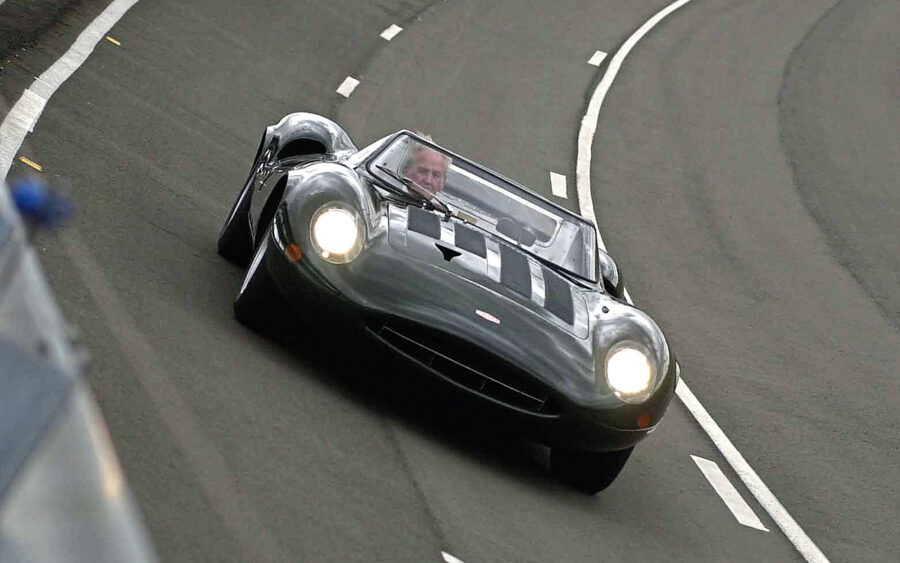

The much-anticipated dual with Ferrari and the Ford GT40 came to nothing when the XJ13 project was canned. But, it did not stop XJ13 from recording the highest ever recorded lap time in the UK, when David Hobbs set a time around MIRA of 161.6mph that would stand for 32 years.

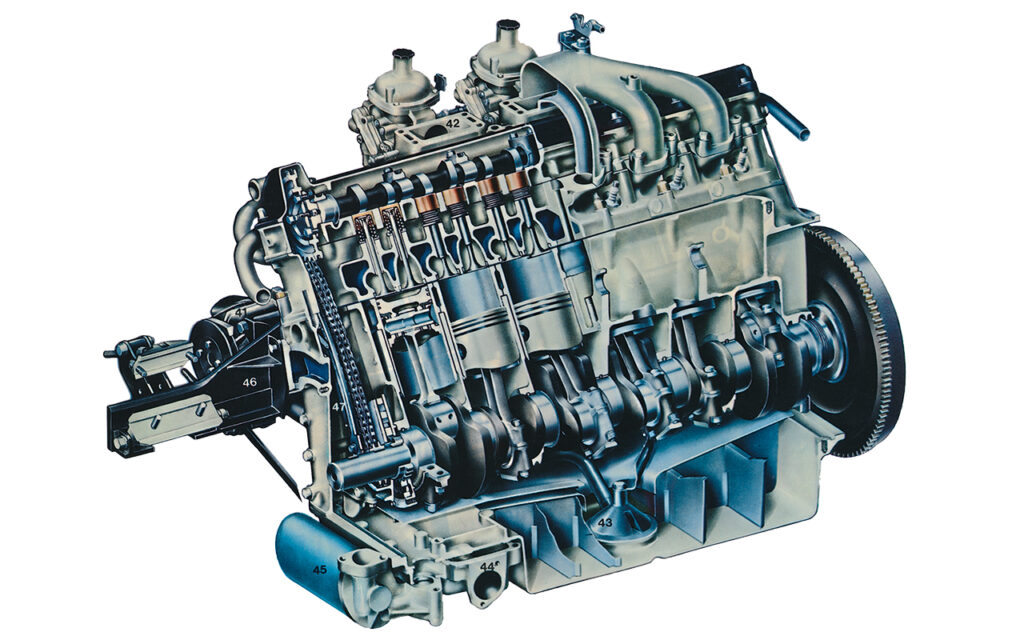

Attention now switched to a full-scale production version, destined to power the most luxurious car in the world. Cost and space implications sent the designers down the single overhead camshaft per bank route, and the findings proved extremely encouraging.

By using a flat head (that is, where the combustion is achieved in the piston crown, the cylinder head face being flat), the single-cam engine held superiority over the twin-cam hemispherical cylinder head up to 5,000rpm. It was only in the upper reaches where the quad-cam engine proved beneficial, although gains were negated by the extra weight.

If time travel were possible, we would request a trip back to 27 October 1971, when director and chief engineer at Jaguar Cars, Harry Mundy, C Eng, F1 Mech E, presented a lecture on the Jaguar V12 engine, its design and development history, to the Institute of Mechanical Engineers at the Mayfair Hotel, London. He gave a very detailed insight of the design, explaining why roller chains drove the camshafts instead of cogged belts, and why fuel injection was aborted (copies of his papers can now only be obtained through commercial auction websites).

Still using the 60-degree V-engine block, the bore for production use was increased to 90mm, giving a capacity of 5,343cc, while, using aluminium, it weighed in at 680lb with all ancillaries – not much heavier than the XK engine. Initially, the use of fuel injection gave some encouraging results, but production difficulties led to Brico, the manufacturer, cancelling the project. Lucas took up the mantle for release in 1975, long after the V12 announcement.

As had become a Jaguar tradition, the new engine was announced in a sports car, despite the intended destination being the luxurious XJ saloon. It was decided to extend the life of the E-type, and, with fewer alterations than might be thought necessary, the V12 was accommodated with ease, albeit on carburettors rather than the promised fuel injection. From the public announcement on 29 March 1971, the world was astounded by a power plant of unsurpassed smoothness. Such was the torque that Jaguar boasted fourth gear could be selected at standstill and the driver could pull away to reach the maximum speed of 146mph without changing gear.

Just one year later, in July 1972, the V12 engine was finally installed into the XJ bodyshell. The XJ6 had already lifted the bar on luxury motoring, so now, with a V12 engine, it set yet another marker for the opposition to tackle.

The E-type was phased out in 1974, to be replaced by the superb, yet controversial, XJ-S. But those early years were not without problems. The Yom Kippur Israel/Egypt conflict had severe implications on the world’s supply of oil, and thirsty engines became decidedly anti-social. Sales of the V12 inevitable suffered and Jaguar needed to address the V12’s thirst.

Swiss engineer Michael May was commissioned to carry out a radical re-think, and, by adopting a system that he demonstrated on his own VW Passat, proved that the adoption of a split-level combustion chamber in the cylinder head allowed lean fuel mixture at 12:1 compression ratio, giving significant gains. The HE (High Efficiency) engine was born. Cars could now return a genuine 20mpg. In 1991, the engine size grew to 6.0-litres in production cars, and would remain in use until 1997, bowing out in the X300.

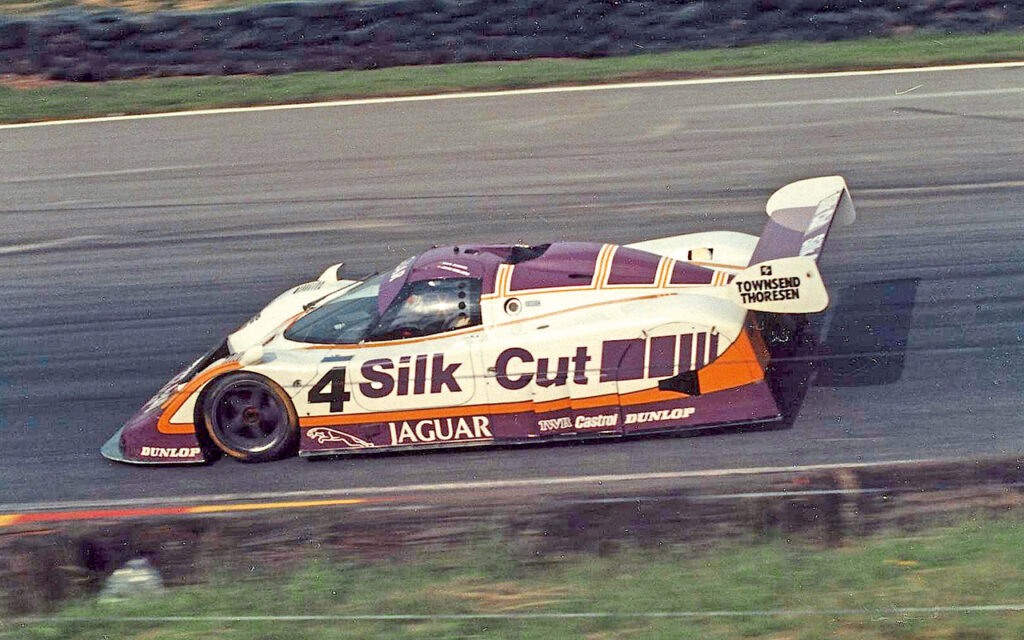

In competition, the V12 had a remarkable career, from the domination of the Group 44 E-type in America, through the ill-fated Broadspeed Coupe, XJS in European Touring Cars, and a return to Le Mans with a 7.0-litre capacity, and two more wins in 1988 and 1990, taking Jaguar’s tally to seven outright victories. In Lister Storm guise, the Jaguar V12 continued to race into the 90s.

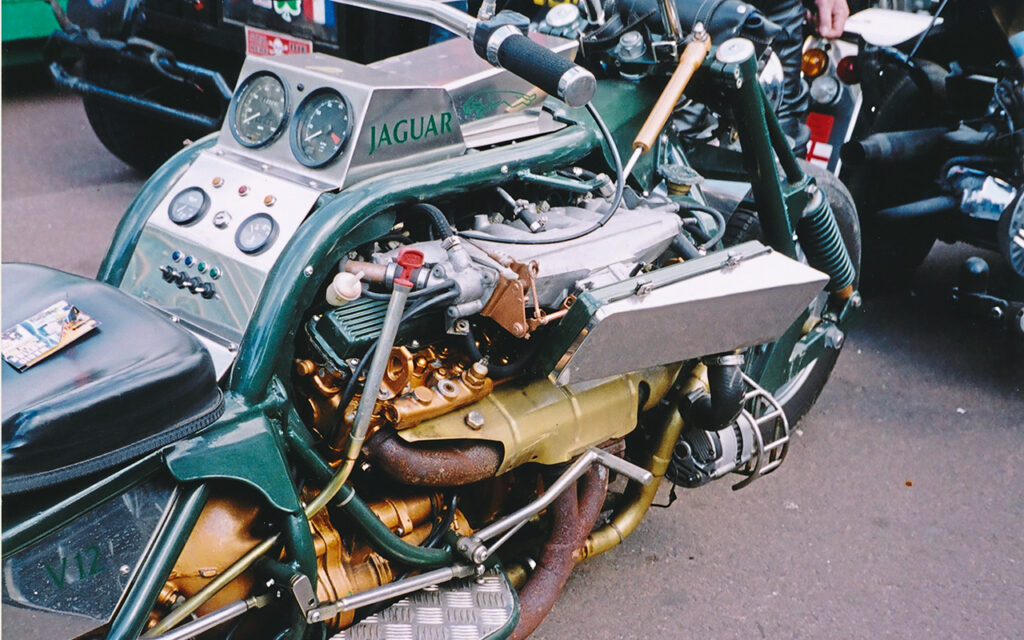

Then along came Malcolm Hamilton, driving the Rob Beere-prepared 7.0-litre E-type. He demolished all before him. Specialists saw the value in this versatile engine, where capacity grew to almost double the first incarnation, to be finally enlarged to ten litres for use in a replica Spitfire aircraft. In turbo-charged form, it developed 1,200bhp for powerboat racing. Unlike any other V12 engine, units were plentiful and provided a base for special builders. Variations could be seen in such cars as Kougar, Panther’s J72 and De Ville, to many one-off specials from a VW Transporter to questionable trikes. Not to mention the occasional Mk 2 and XK installation.

If ever an engine deserved a place in the automotive hall of fame, Jaguar’s V12 should be near the top.