Based on the 1988 Le Mans-winning XJR-9, the TWR-developed Jaguar XJR-15 retained all of the ferocity of the racing car. We try to tame the original prototype at Mallory Park

Words and images: Paul Walton

There’s always a moment when driving even the highest of performance cars when it becomes a little easier, and you start to feel more comfortable with the handling, brakes and eventually the power. You might even forget about crashing for a moment, manage to put aside the images of fireballs and start to enjoy the experience.

This never happened for me with this XJR-15. Even after ten laps behind the wheel, I remained as scared as I did when I first pulled down my visor and accelerated on to Mallory Park’s main straight. As a ferocious, fearsome and frantic car, it retains much of the character of the Le Mans-winning XJR-9 from 1988 on which it’s partly based.

It’s also a car that’s always been misunderstood. Instigated and produced by Tom Walkinshaw Racing with little input from Jaguar and only produced in tiny numbers, little is known about its history, meaning the car has become overlooked in favour of other supercars of the era including its XJ220 sibling.

To try and understand the XJR-15 a little more, we speak to those involved during its development, before driving the original 1991 prototype at Mallory Park.

According to TWR’s then marketing director, Richard West, the catalyst for the car was the team’s victory at the 1988 Le Mans 24 Hours race with the Jaguar XJR-9. “When Jan Lammers, Johnny Dumfries and Andy Wallace won that race, Andy Morrison, the technical director of TWR’s Special Vehicle Operations, said to Tom Walkinshaw he reckoned there was mileage in developing a road car version.” Due to the other low-volume but high-priced models from around the same time – including the Ferrari F40 and Porsche 959 – proving there was a market for such a car, Walkinshaw was interested.

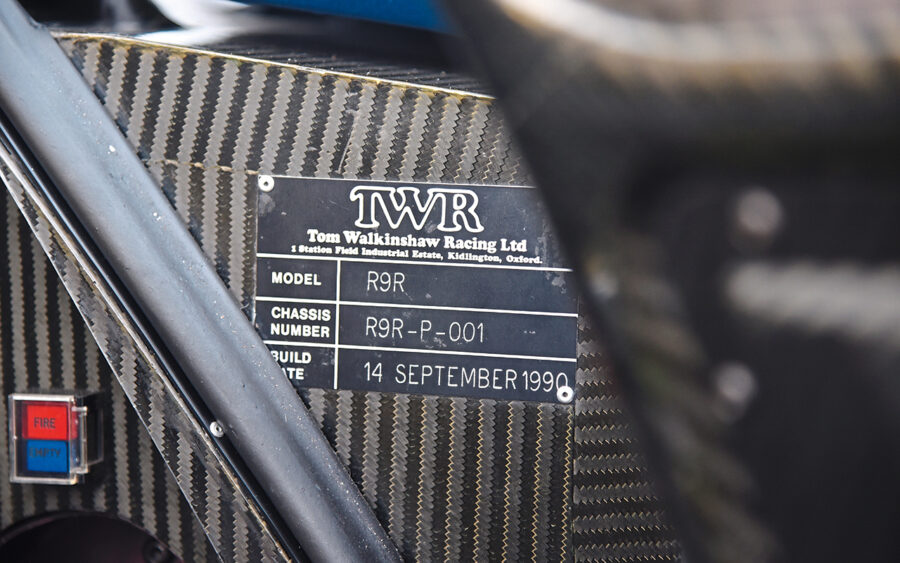

Despite some being eventually registered for the road, from the outset Richard is adamant the car – which was originally designated the R9R – was always meant for the track. “It would have been impossible to get type approval for it,” he tells me. “So in every single contract, it was made very clear these were racing and not road cars.”

Since Jaguar came to TWR to productionise the XJ220 after it had started the R9R project, its own car was done in secrecy and by a small team led by Morrison. It was Morrison who suggested the experienced car designer, Peter Stevens, for the exterior. Following training in the mid-Sixties at the prestigious Royal College of Art, Stevens began his career at Ford followed by a stint at Ogle Design. Stevens began his highly successful freelance career in 1976 and throughout the Eighties worked for a variety of clients including Lotus where he was responsible for the M100 Elan.

And then came an offer from TWR. “I’d known Tom since his British Touring Car years,” Stevens tells me. “I’d done the graphics for some of his previous racing cars plus the aerodynamics for TWR’s Mazda RX-7 that won the 1981 Spa 24 Hours.

“In the late Eighties, Tom was looking to somehow monetise the business of TWR’s Le Mans Jaguars. At first he looked at doing a version of an XJR-8 with a road-going ride height and asked me to do a sketch of what that might look like as a road car which was awful; when you lift a Group C car by 3in, it looks pretty damn stupid. So I said to Tom this wasn’t what he wanted; he needed something completely different. So he said right, come back next week with what it might look like.”

Stevens returned to TWR just two weeks later with some initial drawings. Due to a lack of headroom the designer soon discovered it was impossible to make a road car from a racing chassis. To adjust it accordingly, he was given the tub of the XJR-8 that the British driver, Win Percy, had crashed during the 1987 Le Mans.

“Most of Tom’s drivers were pretty small and it was clear it was too cramped. We had to raise the roof and widen the cockpit inside and make it so there’s a little bit of adjustment for the seat. All of this meant a new monocoque. But Tom was game for that.”

At 480cm long, 190cm wide and 110cm tall, the finished car was slightly larger than the racing car by a few millimetres. Plus, at 1,050kg (2,315lb) it was 170kg (375lb) heavier. It also featured a brand-new chassis developed by TWR’s Jim Router, Dave Fullerton and Eddie Hinkley. Says Stevens, “The philosophy of the chassis was the same and the way the floors were bonded to the side sills came from the XJR-9 but otherwise it was a brand-new car.”

And although as stated earlier, the R9R was sold as a racing car, TWR knew some would be registered. And so it featured rear lights from the Mazda 626 coupe while the front indicators were from the Porsche 944; not only did they keep the cost down but they were already homologated parts.

Yet the R9R still used much of the racing car’s technical specification including the same suspension with the rear uprights, dampers and springs designed to fit inside the wheels, allowing more room for the underwing venturi tunnels. The front springs and dampers were housed horizontally above the driver’s legs much as the same as on the XJR racing cars.

The structural integrity of the Le Mans cars was also retained by the monocoque and panels made from carbon fibre and Kevlar by a TWR-owned company. Explains Richard West, “At the start of the XJR-15 programme, Tom invested in a carbon composite company called Aztec Composites in Northampton that made the tubs for all of the cars.”

The XJR-15 was powered by TWR’s full-fat 450bhp 6.0-litre version of Jaguar’s V12 which, like the XJR-9’s 7.0 had been, remained a stressed member that carried the rear suspension and a five-speed manual gearbox.

Three months after the prototype was finished in September 1990, the car was shown to the press during a special event at Silverstone. The lucky journalists who were invited to drive it all said the same thing; the car was incredibly fast but was also more than a handful.

As World Sports Cars magazine stated in its January 1992 issue, “Levels of grip are far beyond those transgressed by any sane man, except perhaps when exiting a tight corner in a low gear when the sheer grunt pushing you through can persuade the huge Bridgestones to relinquish some grip. Seat of the pants feel and communication is terrific and the steering nicely weighted so that smooth inputs are easy. When it comes to stopping, the huge AP Racing brakes – with softer pads for road use – wash off speed with steely determination.”

By now TWR had come clean to Jaguar about the project, but found the company to be surprisingly positive about a second supercar. So when it was revealed, it was now called the JaguarSport XJR-15, the official link no doubt helping Walkinshaw realise the eye-watering £500,000 price tag.

To differentiate the car from the XJ220, Jaguar’s only stipulation was that it was launched with a high-profile, one-make race series. Says West, “Jaguar said we couldn’t simply launch another car bearing the Jaguar brand and with the Jaguar engine; it needed a different peg to hang it from.”

According to West, TWR’s original plan was to have a series at Le Mans. “We had long conversations with the Automobile Club de l’Ouest [organisers of the 24-hour race] that was very willing about what we wanted but it didn’t happen.”

Around the same time, Tom was starting to have Formula One aspirations and was talking to F1 boss, Bernie Ecclestone, about becoming a team owner. Says Richard, “It was probably Bernie who asked Tom what was he doing with these XJR-15s. And why didn’t he race them at three F1 races.”

This limited series became known as the JaguarSport Intercontinental Challenge. Sixteen cars were modified for racing, the only difference being the five-speed gearbox was replaced with a competition six-speeder.

The three races were held during the Monaco, British and Belgian Grands Prix weekend. Many of the cars were entered by TWR itself and driven by existing Jaguar works drivers such as Derek Warwick, Bob Wollek and Davy Jones. Some, though, were private entries piloted by the owner themselves or drivers from other series.

“It was a bolt out of the blue for me,” said former racing driver, David Brabham, during a 2021 interview. “I didn’t know about the championship; I was racing in Formula 3000 at the time.”

Peter Stevens says that due to producing less downforce than their Group C cars, some of the works drivers found the XJR-15 difficult to drive. “While others worked out it should be driven like an overpowered touring car, the Group C drivers drove it like real ruffians and often went off as a result. But it’s not a car to get angry with; you need to relax and work with it.”

“When we first started driving it, it was a real handful,” continued Brabham, “but after you got used to it you learned to adapt and drive around it and go as quickly as possible.”

While as winners of the Monaco and Silverstone rounds, Derek Warwick and Juan Manuel Fangio II took home £45k plus an XJR-S road car each, for the final race at Spa-Francorchamps the prize money was raised to a cool $1m. “Stocks and shares may be easier,” said the eventual winner, Armin Hahne, during a 2021 interview. “But that was an easy million for me racing on that day.”

Richard West tells me that despite the £100k deposit, there was a lot of interest in the XJR-15 and after Walkinshaw initially said just 25 would be built this was soon increased to 40 and again to the eventual 50. The cars were produced at TWR’s Kidlington factory where the Group C racing cars were prepared and not, as often stated, at JaguarSport’s Bloxham facility with the XJ220.

Following the prototype and the 50 production cars there was also a 52nd example which, like the first example, was badged R9R. According to Peter Stevens this is because having a contract with Jaguar to produce 50 JaguarSport XJR-15 branded cars, Walkinshaw wanted to sell ten more under the R9R name but only one of this second series was produced.

Richard tells me of another five cars that were built after production had ended for a customer in Japan which featured slightly longer bodywork and a different front splitter plus the same 7.0-litre V12 as the TWR’s Group C racing cars. Rarely seen in the intervening 20 years, these have since become known as XJR-15 LMs.

It was also the basis of the TWR-designed Nissan R390 GT1 endurance racer that used the same basic monocoque, but was powered by the Japanese company’s 3.5-litre turbo V8. Produced largely to win the Le Mans 24 Hours race, its highest finish was third in 1998.

Despite being made in tiny numbers, the XJR-15 was an extremely important car. Richard West reckons it helped TWR pay for developing the Aston Martin DB7 plus it influenced Stevens’ next project, the McLaren F1.

“I actually took Gordon Murray up to TWR to look at the way we were doing it,” says Stevens. “And I told him if we try and do something too complicated, particularly at the time with carbon, it either will be made of multiple pieces, which had to be so carefully put together, or it doesn’t work because I described carbon as being about as handy as boilerplate in terms of moulding it, because the whole point of carbon is the fibres are so stiff, that you can’t persuade it to go where it doesn’t want to go.”

According to West, the car had an impact on the McLaren F1 in another way, too. “McLaren’s Ron Dennis [who Richard had worked for during the mid- to late-Eighties] called me in early 1990 and asked what these things were going to sell for? When I said it’s no secret they’ll be £500k, Ron asked what makes us think we can get that kind of money? I replied there’s 50 people in the world who would like to own what looks like a racing car with a V12 hanging out the back of it. When I said why was he asking, he said McLaren was building a three-seater and hadn’t yet decided on the price point.” When the F1 eventually went on sale in 1992, it was priced at £540,000.

Yet while the McLaren together with other supercars of the era, including the Porsche 959 and Ferrari F40, have always been celebrated, the XJR-15 is now largely forgotten. Its confused parentage is partly to blame plus Jaguar has never taken ownership of the car in the same way it has with the XJ220, meaning it’s become a footnote in the company’s history. Plus, with the 50 XJR-15s now spread across the globe, often hidden from view in private collections, they’ve become an increasingly rare sight.

One, though, has made a welcomed and visible return to the track.

According to Richard West, the original 1991 prototype was a hard-worked development hack. “It had everything tried in it; five-speed ‘box, six-speed box, V6 twin turbo, V12. You name it, that car had every single mechanical process you could think of put on it.”

The car was initially retained for Walkinshaw’s personal use who, as a former racing driver, usually drove it flat out which Richard experienced first-hand. “Tom once turned up in my office and said, ‘Come on laddie, I’ll take you for a wee ride.’ We went round the lanes at well over 100mph, sliding about all over the place, drifting through roundabouts. And I thought to myself, ‘Who in God’s name is going to end up with one of these things?’”

At some point the car was sold by TWR and began travelling the globe, becoming a part of different car collections. After spending time in both Australia and America, in 2013 it was for sale through a Belgian dealer when its online advert caught the eye of a British enthusiast, Andrew Maynard, despite not knowing what the car was.

“I was surfing the internet looking at classic cars,” Andrew tells me, “when I came across this Jaguar in a garage in Belgium. I looked at it and thought, ‘Wow! What’s that?’ I’d never seen one before.’” After visiting the dealer and hearing the V12 run, Andrew knew he had to have it.

Having been stood for several years, it needed recommissioning by leading XJ220 specialist, Don Law, in Staffordshire. With the car up and running once again, Andrew is becoming a regular at trackdays and has invited me to drive it at JEC TrackSport’s event at Mallory Park in Leicestershire.

I’ve been fascinated by the XJR-15 since reading about the Intercontinental Challenge in the early Nineties, meaning when Andrew slowly rolls the car out of his covered trailer, I feel a tingle of anticipation down my spine. Or is it a raindrop? It’s not the greatest of days to test a 190mph supercar.

But what I find most worrying is the lack of aero aids that usually cover supercars like this, a conscious decision by Stevens to keep it driveable. “If you had 1,000 lbs of downforce at 100mph, it would result in 4,000 lbs of downforce at 200mph which, due to the technology of the time, would result in the springs becoming like a pickup truck’s making it ride appallingly badly. So my idea was there should be a little downforce but it should be balanced, front to rear. What you want is the downforce to be active through the same point as the centre of gravity so as you go faster, it doesn’t change its attitude; the nose doesn’t come up or drag on the ground.”

This resulted in a very simple design which in my view makes it better-looking than other low-volume supercars of the era including the Bugatti EB110 and Mercedes CLK GTR, while it’s also smaller and more compact than the overly voluptuous XJ220. “When Tom and I saw the XJ220 at the Birmingham Motor Show,” Peter told me earlier, “he didn’t think it was a TWR kind of project; he said it was a big grand tourer. He wanted to do something that connects people more directly with the feel of driving a Le Mans car.” And judging by the exterior, they achieved that.

Other than the TWR 9R badge on the nose, the prototype is largely identical to the 50 XJR-15s, even down to the same shade of Mauritius Blue the production versions were only available in. The bodywork does feature a line of rivets whereas the panels on the later cars were bonded together. Plus, the prototype originally had a NACA-style duct in the rear which Walkinshaw didn’t like and so was covered over, but is still visible in the engine bay.

After Andrew completes a few warm-up laps he returns to Mallory’s paddock and kindly invites me into the driver’s seat. Due to the lack of room there’s no easy way to climb in; he instructs me to stand on the driver’s seat and wriggle under the flat-bottomed steering wheel before leaning at an awkward angle to slip my helmet on. It might be larger than the cockpit of the Le Mans-winning XJR-9 I sat in during a 2013 photoshoot, but as Andrew and I sit uncomfortably shoulder to shoulder, it doesn’t feel it.

With the four-point harness clicked into place, I take stock of my surroundings. Unlike the XJ220’s dashboard that with its traditional-looking plastic dial binnacle, air vents and radio makes it look and feel like a fairly standard road car, the XJR-15’s interior isn’t far removed from the racing car on which it’s based. Constructed largely from unpainted carbon fibre and offering little in the way of comfort, this harshness is an early illustration of the car’s unforgiving character.

Under instruction from Andrew, I turn the red kill switch upwards and then, feeling like a Spitfire pilot, click the four flicker switchers to the right of the steering wheel for the ignition, injectors, fuel pumps and finally the starter. The huge six-litre engine behind me mechanically churns over before bursting into life with a loud roar, settling down to a throaty crackle. I grope around to my right for the gearlever and after finding first, gingerly release the clutch and weave through the busy paddock as many onlookers strain for a better look of this rare car.

After being waved on to the track by a marshal, I join just before Mallory’s long right-hander, Gerard’s Bend, which slowly unwinds into a short straight where, with the track starting to dry, I press the throttle as hard as I dare. The engine responds instantly, resulting in a hard and unbridled burst of acceleration, the cramped cabin filled by the deafening roar of the V12.

With the revs rising quickly, I again reach down to the gearlever and look for third and fourth. Finding the gearbox notchy and unforgiving, I need to physically force the lever into position, making changes tricky to get right and I often engage the wrong gear by accident.

With the John Cooper Esses – a right- and then left-hand corner – fast approaching, I gently squeeze the brake pedal but find not much happens; non-servo assisted, I need to press as hard as I can for them to work. After changing down to third to release more of the engine’s torque, I turn into the corner and although the unassisted steering is heavy it’s also sharp, accurate and barely needs any movement on the wheel to get through.

Next up is the trickiest section of Mallory, Shaws Hairpin. The tightest corner of any racetrack in the UK, it’s made more difficult due to a slight incline halfway round. Andrew warned me beforehand that if I accelerate too hard out of the bend the car could spin so after changing down to second I gently nurse the car round before trying to line up for the oncoming Devil’s Elbow. A gently tapering bend that also features a change in camber, it’s difficult to get right in a car equipped with traction control never mind one with 450bhp that doesn’t.

Stevens might have limited the amount of downforce but together with the fat tyres finding grip on the still greasy surface, there’s enough for the car not to feel unsettled through the awkward bend, allowing me to carry plenty of speed for the oncoming start/finish straight.

Although over the next half an hour I learn more about the car, eventually becoming brave enough to brake later into corners before accelerating earlier out of them, as I said at the start, I never feel totally at ease. Its old-fashioned analogue performance, which is difficult to master, more so than the Ferrari F40 I was lucky enough to drive a few years ago, that felt like a nimble go-kart by comparison.

After ten laps I feel like I’ve reached the limit of my abilities and so following a cooling-down lap I head back to the safe confines of the paddock. As I turn off the engine by clicking the same four switches at the same time with the side of my hand, I start to have mixed emotions about the experience.

To drive an XJR-15 has been a long-held ambition and thanks to its power, grip and noise, it didn’t disappoint. But it’s also the most brutal car I’ve driven, meaning I’m secretly pleased my time is over and the car is still in one piece.

The XJR-15 might not be a pure Jaguar but thanks to its close links to the Le Mans winner, incredible performance and rarity, it should be one that’s better remembered than it currently is. After those ten astonishing but also scary laps, it’s certainly one I won’t forget.