This one-off special might look like a pre-war racing car but it was made in the late 2010s and is based on the running gear of a 1959 Jaguar XK150

Words and images: Paul Walton

It’s hard to know who or what to believe these days. If it’s not politicians covering their tracks then it’s emails pretending to be from the bank or fake Rolexes sold as real ones.

Then there’s this grey two-seater. Judging by its long, low, and rakish design, the car was clearly designed and built in the Thirties. But that’s a bigger mistruth than that £30 Submariner you bought on the beach last summer because not only was the car put together in the late 2010s but beneath that handsome body is the chassis and engine from an XK150. Although this means the car’s image is a huge lie, its performance is anything but.

The project started in 2017 when Max Szewczyk, an aluminium fabricator based in Ilford, East London, bought a 1959 XK150 3.4 fixed head coupe (chassis 824682) that he originally planned to transform into a stripped racer. But when he began taking the car apart he realised the body was in a worse condition than he thought. “It was a bit of filler car,” he tells me over the phone when I call his workshop. “When I dug into it, the body was beyond salvage.”

With replacements too expensive and Max saying he didn’t have the knowledge to make one himself from aluminium, he decided on anther route; he would reclothe the chassis in the style of a 1930s racer. “It’s a period of cars I like and have worked on a lot,” Max tells me. “It’s everything I know put into a single car.”

From Bentleys to Bugattis, he freely admits to being influenced by several different models, but one more than so than the others; a unique Model 40 Special Speedster built for William Ford’s son, Edsel, in 1934.

With no real plan, it was a case of trial and error until Max got the lines and proportions he was happy with. “I roughed out the basic shape but it changed a lot. I originally tried to use the original XK150 grille in the design but it didn’t work.” Max made all the panels himself, using the traditional English wheel to get the lines and shapes he wanted.

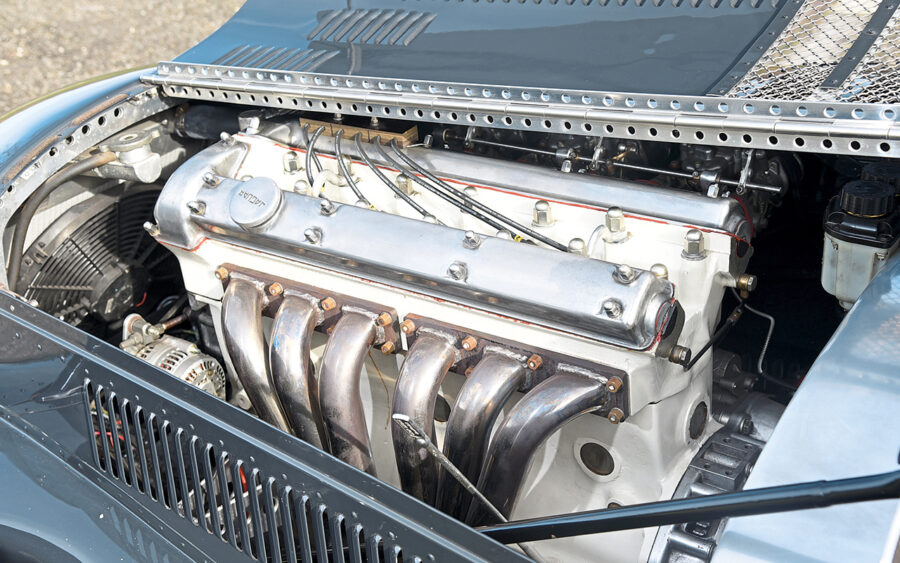

Although he tells me he was, “more concerned about how it looked than how it performed,” he still spent time improving the car’s performance. The 3.4-litre XK unit was retained but rebuilt with a modified cylinder head with breathing through special triple twin-choke Webber carburettors. To make the car more user-friendly, Max replaced the XK150’s original gearbox with a modern Toyota five-speed unit while the disc brakes and suspension were both beefed up.

Due to having to fit the Jaguar around customer projects, it took Max three years to complete his XK150 Special. Fully road legal, it’s now for sale through Sovereign Car Sales in Whitchurch, Hampshire, who invited us to see the car.

From the purposeful stance to the long, sweeping lines, the open cockpit to having more vents than a power station, it looks every inch the pre-war racer. It’s not too hard to spot several elements where Max was clearly influenced by other cars. The integrated headlights, for example, make the nose look a little like Edsel Ford’s Type 40 Special Speedster while the overall proportions are similar to those of the 1935 Alfa Romeo Tipo C 8C 35 and the tightly tapered ‘boat tail’ is pure Bugatti Type 39. Finally, the oval-shaped bonnet bulge that runs down the driver’s side behind the grille and houses the carburettors is reminiscent of those fitted to several sports cars from the period. Yet it’s not a pastiche or direct copy of any particular model and has its own distinct character and personality.

Max’s attention to detail is clearly on another level to us mere mortals since not only does every rivet and screw line up but there are several clever little touches. The twin exhausts, for example, discreetly exit through the rear light pods that look like short, stubby airplane wings.

A small point, but I really like the colour. Instead of something obvious like British Racing Green or Rosso Corsa, Max decided on an attractive shade of mid grey. Together with the black wire wheels and unpainted aluminium mesh grilles, the old-fashioned hue does almost as much as the design in the illusion that the car is older than it is but without trying too hard.

With no doors, I swing my legs one after another over the low side and then slide down the richly upholstered red leather seat until I’m behind the large wooden steering wheel. Due to having ridiculously short legs, I try to move the seat forward only to find it’s fixed in position. Looks like I’ll be engaging the clutch using just my toes.

Max’s eye for detail is again evident by the identification of the switchgear that’s been engraved directly into the aluminium dash and then painted yellow. The result is a basic almost military look but one that’s still more stylish than most production cars.

When I later say to Max the single Bakelite unit of five toggle switches in the middle of the dash have an aeronautical feel, he laughs and reckons it probably came from a Lancaster bomber.

Other than the digital speedo (which looks as out of place in the old-fashioned cockpit as an iPhone would in a Charlie Chaplin film), the majority of the instrumentation is from the XK150 donor car. Yet to the far left of the dash is what looks to be an antique Russian stopwatch.

“It’s something I picked up and set it in there since it I thought it looked right,” Max tells me. He’s not wrong; the slightly battered dial and the green Cyrillic writing appears strangely at home in this antiquated-looking car. Plus the unusual clock together with the plane-sourced switches further adds to the impression this is a home-built special from the Thirties that utilised whatever parts were lying around at the time.

Starting the engine is as exciting as I hoped it would be. After clicking up two of the toggle switches to turn on the ignition and fuel pump – their action offering the perfect amount of resistance – I press the starter button. The 3.4-litre XK unit bursts immediately into life, its familiar raspy growl made louder by the lack of roof or any sound deadening.

With the road ahead of me clear, I pin the throttle to the uncarpeted aluminium floor, the engine immediately responding as I do. It’s not known how much Max’s Special weighs but considerably less than the 1473kg the XK150 would have weighed would be my guess.

This lightness together with the 3.4-litre clearly producing more than its original 210bhp results in the acceleration having a harder, keener, and sharper edge to it. The power arrives much quicker than that of a standard 3.4-litre XK150, forcing as much air into my face as wing walking on an old-fashioned biplane would. By being quicker and more precise than the standard gearbox the car would have originally come with, the modern Toyota replacement further aids this swift performance.

Not that I need to go all that fast to feel as if I am. With the tiny screen offering as much protection as a linen suit in a storm and the sides so low I can lean out and touch the floor, even 30mph gives the impression I’m barrelling around Brooklands, fighting for position with the Bentley Boys. Marry this with the loud bark from the exhaust and it’s an unforgettable experience.

Although the big, 600 x 16 Blockley cross ply tyres offer plenty of grip in these wet and greasy conditions, in my opinion they make the steering a little too vague and prone to tramlining, lacking the sharpness of a standard XK150. Admittedly they look great, their size and old-fashioned tread further aiding the illusion the car is from the Thirties, but personally I’d have fitted a more modern radial for improved steering. But this is a minor criticism of what is otherwise a fabulous conversion.

As a pre-war racer, Max’s XK150 Special might be faker than that last email you received about a bogus bank loan, but there’s no doubting the legitimacy of its performance, character or looks.