Lynx’s Jaguar replicas have become almost as collectable as the real thing. After sampling this Lynx D-type, we find out just why

Words and images: Paul Walton

Due to their accuracy and the fact the real thing is usually expensive, some examples of fake artwork have become highly sought-after and therefore expensive. For example, in 2021 a copy of Leonardo’s famed masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, sold for an incredible $3.4m. The auction house that sold it, Christie’s, said the replica, “is not as compelling as the work in the Louvre but it conjures something of that world and, in a world of images, in which only the strongest ones stay in our mind, allows the dream to go on.”

I’m sure anyone who owns a Lynx replica of a D-type feels the same way. Due to their accuracy, high performance and unrivalled pedigree, like that fake Leonardo, they’ve become almost as collectable as the real thing.

Yet when Guy Black started the Sussex-based company 55 years ago, he never had any intention of producing replicas. The former R&D engineer at Weslake simply wanted to restore classic cars, calling his burgeoning company Lynx after a Riley he was working on at the time.

It was the restoration of a C-type in the early 70s that was quickly followed by others that led Lynx to become one of the world’s leading experts in Jaguar’s famed racing cars. “It became obvious to us that we had unwittingly tapped a market we didn’t even know existed and so we ended up doing a whole string of them,” said former Lynx director, Chris Keith-Lucas, in the March 1990 issue of Motor Sport magazine.

Their expertise perhaps naturally led to the company producing an all-aluminium replica of the 1956 Le Mans winning long-nose D-type which was revealed at the 1974 Racing Car Show at Olympia. Not only did it look physically identical to the original but it used much of the running gear of an E-type meaning unlike many fakes that used a variety of incorrect running gear, it had the right pedigree too. The only major change was the use of the latter’s independent rear suspension rather than the solid live axle of the original.

“We are in the unique position to manufacture the most authentic possible reproduction of the ‘D’ type Jaguar,” said a single page flyer from Lynx in the late 1970s, “as our restoration department’s main work is the restoration and maintenance of the original cars.”

But the kind of accuracy that Lynx managed to achieve came at a cost. At £18,500 (excluding VAT) in 1979, it made the Lynx D-type four grand more expensive than a brand new Jaguar XJ-S. There was a £1000 rebate, though, if the customer supplied a six-cylinder E-type donor car. Lynx also offered a DIY kit including everything needed to turn an E into a D for a little under nine grand.

Yet despite the price, due to its reputation for accuracy and for being considerably cheaper than one of the 75 originals, over the next two decades Lynx built 53 examples which included nine in finless XKSS form.

Thanks to their perfect lines and flawless heritage paired with the Jaguar running gear and aluminium body, these Lynx-built D-types (plus its C-type replica that arrived a few years later) are now highly sought-after, demanding relatively high prices for what is ultimately a fake.

Take this gorgeous British Racing Green example that was built in 1987. Although considerably worth less than the real thing, its current value of a little under half a million is still much more than an early E-type for example.

I’ve been lucky enough to have driven three original D-types over the years including the original prototype XKC401, plus XKD526 which had a fine career in Australian club racing and XKD603, the car which finished second at the 1957 Le Mans 24 Hours.

And so using my limited experience, it certainly has all the stage presence of those genuine cars. With its period-correct lightweight Dunlop alloys, the outrageous fin behind the driver’s head and tiny Lucas-sourced rear lights, I doubt even Jaguar’s former test driver, the late Norman Dewis, who spent more time driving D-types than anyone, could differentiate it from the real thing.

As I open the flimsy aluminium door, swing my left leg over the wide sill before standing on the seat and slipping down behind the wheel in the same way I’d get into a bathtub, this accuracy continues inside.

It’s not that it’s a tight fit or that the dash is dominated by the huge Smiths white-on-black speedo and rev counter that makes it so; it’s the crudeness. The warning lights on the dash, for example, have old-fashioned Dymo tape underneath just as XKC401 and many other original racing cars I’ve driven did.

Other than the obviously road-car sourced chrome handbrake lever – which in these austere surroundings appears out of place – it could easily be the real thing.

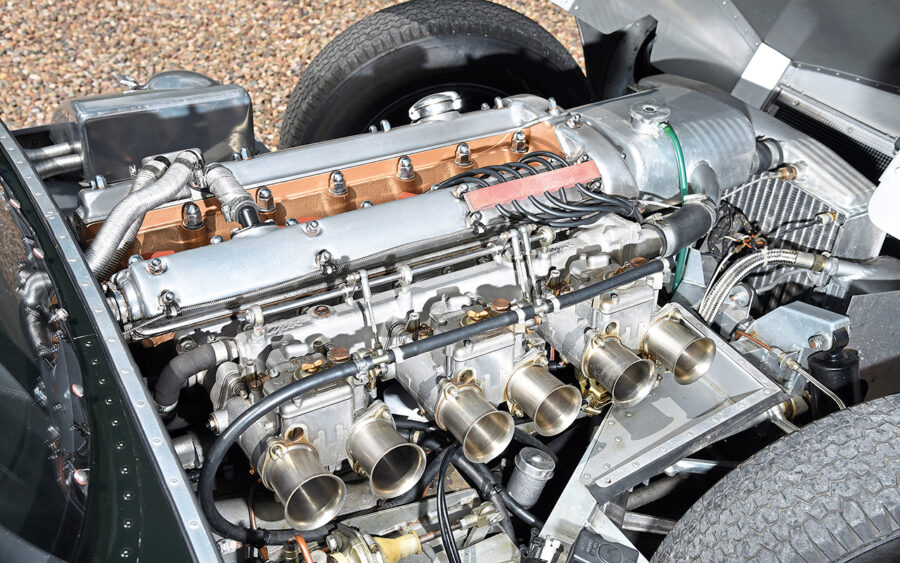

This authenticity is further established when I press the starter button and the peace and quiet is shattered by the instant roar of the straight-six unit. Originally a 3.4-litre, it’s been bored to 3.8 and together with porting and polishing, D-type cams, high compression pistons and Weber carburettors is now pumping out over 300bhp.

On a long stretch of clear road, I flick down to third and nail the throttle as hard as I like to think Mike Hawthorn would have done on the Mulsanne Straight on his way to winning the 1955 24 Hours of Le Mans in a similar-looking car. With so much power yet the all-aluminium car weighing less an E-type, the acceleration is instant, hard and raw, the countryside filled with its distinctive raspy exhaust note.

Being slightly taller than the Perspex screen, I do feel as if I’m in a wind tunnel and my hair now has a major flyaway look but as I pick the flies from my teeth, I decide that’s all part of the authentic experience.

The engine’s mid-range punch is especially strong; squeeze the throttle while burbling along at 4000rpm and it still responds instantly, the car surging forward with a confidence only racing machines, even faux ones like this, can possess.

The four-speed manual transmission then offers short, snappy changes that slot into place with the same smoothness as the bolt action of a well-oiled Lee Enfield rifle.

With perfectly balanced and accurate steering that feels considerably more direct than an E-type’s plus barely any body roll, it allows corners to be attacked rather than just taken. Admittedly it’s a dry, sunny day but as I balance the throttle through the bend before giving it the beans on the exit, there’s no danger of the rear end breaking away. Hawthorn would be proud.

Rather than being disappointed it’s not real, I’m sure whoever bought that fake Mona Lisa is enjoying the picture for what it is – a perfect facsimile of a famous picture. The same goes for this Lynx D-type. It might not be genuine but it looks like one and drives like one. And that’s enough