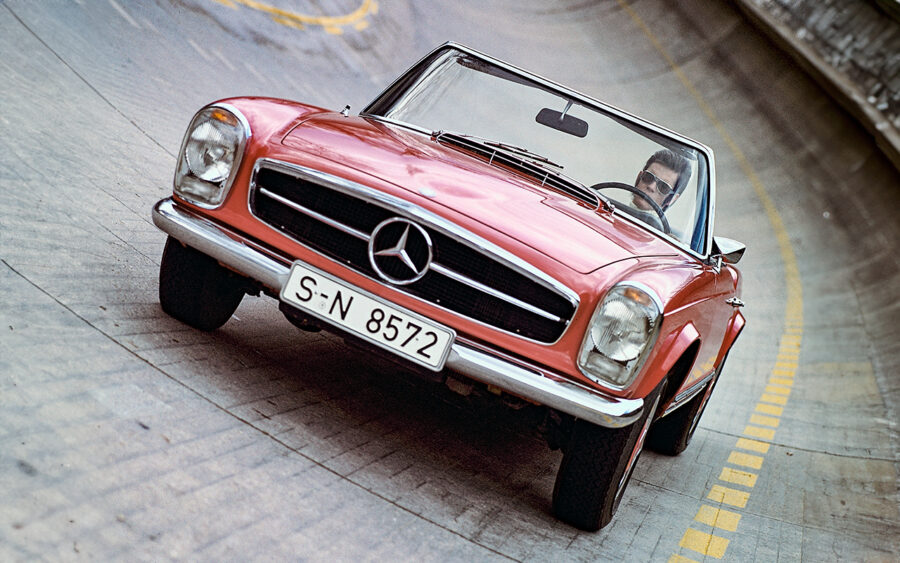

The ‘Pagoda’ W113 SL has become an icon of the 1960s and even today there are few cars quite so glamorous

Words: Sam Skelton Images: Mercedes-Benz

Think of 1960s celebrities and eventually the topic will turn to the Mercedes SL. Everybody who was anybody had one – Audrey Hepburn, Sophia Loren, Peter Ustinov and Sir Stirling Moss have all owned and enjoyed the sporting drophead. Even today, it’s enjoyed by the rich and famous: Ryan Giggs, Kate Moss, Nico Rosberg, John Travolta and Harry Styles all have had a Pagoda on the drive.

Over the course of the W113’s run, Mercedes tweaked the formula, pulling it further from the original lightweight sports concept and further toward becoming a GT car. And while those later cars are quicker, there’s little difference in terms of the market today – whether a 230, 250 or 280, all W113 SLs are seriously desirable classic roadsters.

By the late 1950s it was evident that the Mercedes SL concept needed a revamp. The 300SL supercar was beyond the reach of most, and the 190SL was underpowered and becoming dated in design. The company experimented with an update of the 190 – known as the 220SL to reflect its larger engine, this car was given the development code of W127. However, production difficulties meant the project was delayed repeatedly; its original planned July 1957 launch passing unnoticed. By7 1960 it was concluded that a new model, based on the W111 and using technology from the W112, would be a wiser solution. Three years later, the 230SL was launched – dubbed the W113.

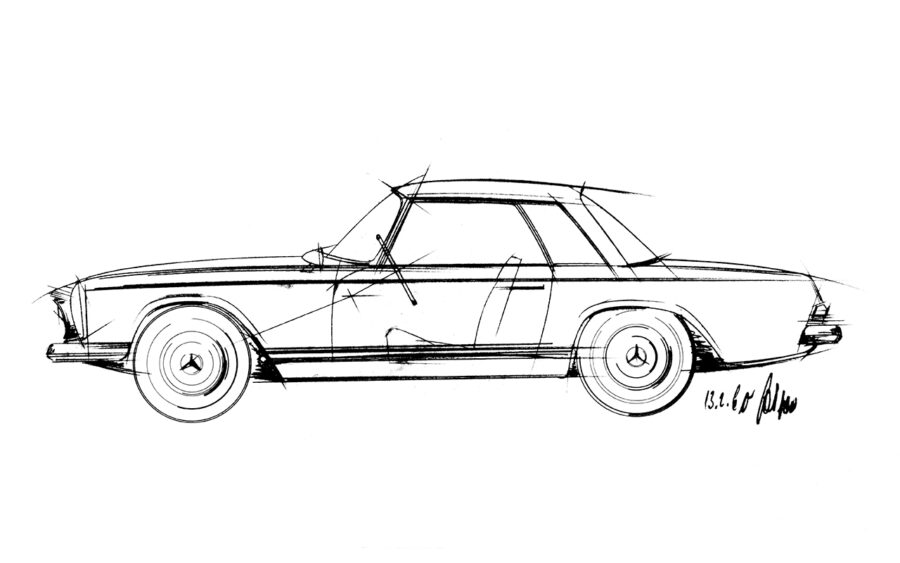

Paul Bracq was responsible for much of the styling, but the famed hardtop roof – the item which led to it becoming dubbed the Pagoda – was the work of Béla Barényi. Barényi was also responsible for some intelligent aspects of the car’s design. It was the first sports car to be designed with safety in mind, featuring front and rear crumplezones and featuring rounded cabin edges in the style of the W111 which spawned it.

At launch, Mercedes’ chief engineer performed an impressive stunt to demonstrate the capabilities of the new SL. Grand Prix driver Mike Parks had previously lapped the three-quarter mile Vétraz-Monthoux racing circuit in Annemasse in 47.3 seconds, in his Ferrari 250GT. Engineer Rudolf Uhlenhaut achieved a time of 47.5 seconds in a brand new 230SL, despite a deficit of almost 100BHP and 6 cylinders. While the SL may not have been a sports car, it was certainly sporting enough.

Styling sketch by Friedrich Geiger, 13 February 1960

In 1966 Mercedes updated the concept with the more powerful 250SL, which brought rear disc brakes and increased power to the SL range. The fuel tank was increased from 65 litres to 82 litres, and a limited slip differential became available as an option. The 250 was also made available as a 2+2; the California Coupe. This model replaced the convertible hood with a vestigial rear seat; and while the car was supplied with a hardtop this was removable for those who wished to take the risk of sudden downpours.

In the following year, 1967, Mercedes launched its final W113 derivative, the 280SL. Power was once again increased, though the whole car was softened to reflect its new status as a GT rather than a sports car. It marked the end of development for Mercedes’ SOHC six cylinder engine, This final evolution was the strongest-selling W113, with the majority of production heading to America as automatic transmission models. Mercedes, aware of the direction the market for prestigious convertibles was heading, developed the replacement R107 SL with a focus on touring ability rather than sporting prowess. Its launch in 1971 as the 350SL marked the end of W113 production, and the end of one of the most special eras in the SL model’s lifetime.

To understand and appreciate the way a W113 SL drives, you need to adjust the way you think about how a car should perform. It’s not fair to judge this on speed, or noise, or handling, or ride. While it acquits itself fairly on most measures, the best way to consider it is in terms of how it makes you feel. And at that, the SL is fantastic. You catch yourself watching your reflection in shop windows, enjoying the turning heads as you glide past.

And you can understand why when you take a step back and look at it. The lines are really rather simple, yet there’s plenty to notice. The small hips behind the doors, the delicacy of the tail, the stacked lights – none of it is overdone or gaudy, and yet you sense that more attention and care has gone into this shape than most.

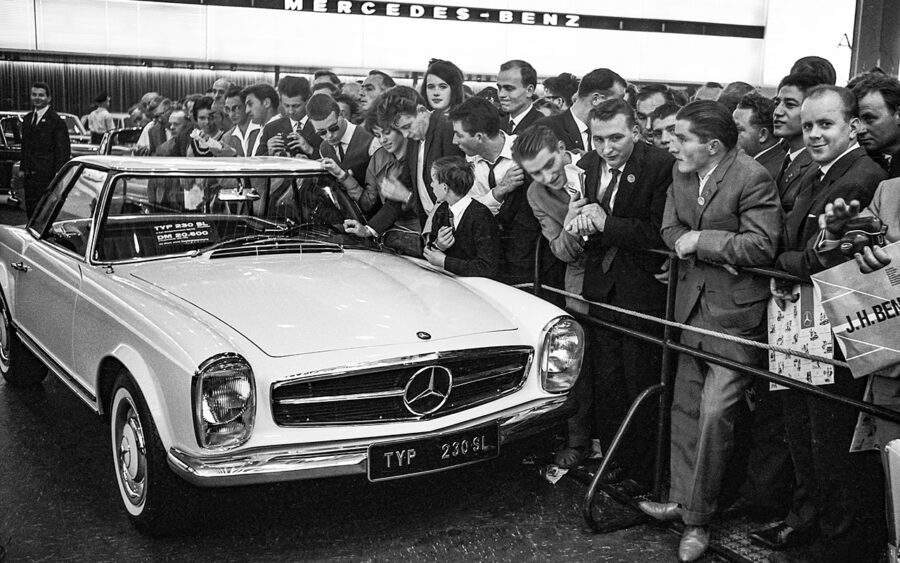

Mercedes-Benz 230 SL ‘Pagoda’ (W113) at the International Motor Show in Frankfurt am Main (IAA), September 1963

All the touches that make 1960s SLs so special – the Art Deco façade, the nice use of wood, and the big horn push – all set it apart from mere sportscars or pseudo GTs. It might be a 1960s car with vinyl trim, but knowing you’re driving something so stylish sets it apart from the rest. It’s not especially quick, despite the 2.8-litre engine in the car we tested, but the SL was always more cruiser than sports car.

The kickdown of the four speed automatic gearbox and sweet sound of this six-cylinder engine encourage spirited driving, although the light power steering doesn’t. This is a little different in the manual – the bias feels more athletic because you’re making more of the decisions, having more of the input – but in a smooth riding GT, somehow it feels more appropriate to let the car do the work and to enjoy the experience.

While it’s more comfortable cruising the seafront at Monte Carlo, the SL handles really rather tidily. It’s not communicative in the classic sportscar manner. But what it does is it makes the process of driving quickly feel so easy. Although many feel a GT should be a heavy, hard going, muscular experience, the SL looks the other way. Instead, it’s the car into which you could get in London, and emerge in the South of France without worry or exertion.