The 930’s body was so attractive that in 1983, Porsche applied the formula to a naturally aspirated 911. Based on the Carrera 3.2, the resultant Super Sport has the substance to back up its style

Words: 911 & Porsche World staff

The shape that Porsche devised for the original 911 Turbo was iconic the moment it was unveiled at the Paris motor show in 1974, in defiance of the so-called oil crisis that was gripping the world and threatening to drive sports cars out of existence. Every aspect of the 930 model, as it was factory-coded, defined power, engineering and aggression: the massively bulging wings, eight-inch wheels, deep front spoiler and whale-tail rear wing. The term ‘supercar’ had just been re-defined, and a model created that remains at the top level of the 911 armoury today.

The astonishing shape was always going to be too good to be restricted to just the flagship model, but it took Porsche almost a decade to apply it to normally aspirated 911s. It came in 1983, a Carrera 3.2 featuring the widened Turbo body and some chassis upgrades, but with the standard 911 Carrera engine; at this point referred to as ‘Turbo Look’, the ‘Super Sport’ name coming later.

As with all air-cooled 911s, values of these began heading through the roof several years ago. But when this variant was first launched, there were some who called it a ‘sheep in wolf’s clothing,’ and, with its added weight, dismissed it as a cynical marketing exercise that contravened Porsche’s engineering maxim of lightness and efficiency. But from a perspective of more than 30 years on, how does the Turbo Look/Super Sport sit in the Zuffenhausen hall of fame, and what should you be looking for if considering purchase?

Porsche calculated that a sufficient number of customers in Europe and the US would like a 911 with the appearance of the Turbo, but would be happy with the performance of the Carrera 3.2’s flat-six with Bosch L-Jetronic fuel-injection giving 228bhp and 210lb ft. And for some, the fiery sound of the normally aspirated 3.2 engine was more appealing than the flatter and less invigorating tone of the 3.3 turbocharged unit.

An additional factor was that the 911 Turbo had, for emissions reasons, been withdrawn from the US market in 1980 (and would remain off the price list until 1986), which not only deprived customers there of Porsche’s ultimate body shape, but galvanised independent tuners into offering re-bodied Carreras. Hence under the factory’s Sonderwunsch (Special Wishes) programme for special builds, in September 1983, for the 1984 model year, European and US buyers were offered option M491, the Turbo body.

Besides being 123mm (4.8 inches) broader at the wheel arches, and using the accompanying wider front and rear tracks, it featured the Turbo’s uprated braking system, derived from the 917 Le Mans race car, and firmed and lower suspension. 16-inch wheels were fitted (as on Sport models), the fronts seven inches wide and with 205/55 tyres and the eight-inch rears shod with 245/45s.

For the next five years until the next-generation, 964-model 911 arrived, the fatter Carrera 3.2, weighing an extra 50kg, received the same updates as the regular model. For 1986 equipment was upgraded and there were minor tweaks to the fascia including larger air vents. But a more significant development came one year later, in September 1986, for the 1987 season, the G50 gearbox was fitted, the Getrag-built unit replacing Porsche’s 915 unit, and accompanied by a larger, hydraulically rather than cable-operated clutch, its larger casing necessitating changed rear suspension mounting points; a G50 is identified by the reverse position, to the left and next to first.

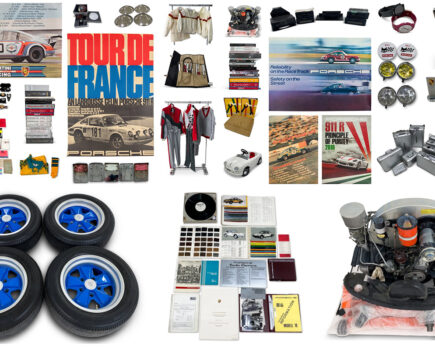

A year later, for the 1988 model year the wide-bodied car was given its own official title, appearing on the price list as the 911 Carrera with Super Sport Equipment, a model that should not be confused with the narrow-bodied 911 Carrera Sport, or the 911 Turbo with Sport Equipment, which was the ‘Flatnose’ Turbo. A specific model, it was offered in coupe, Targa and Cabriolet forms. However, Super Sport was never a badge on a car, merely wording in brochures. An estimate by Porsche Club Great Britain puts the total number of Turbo look and Super Sport 911s delivered worldwide at 1580.

It’s interesting to look at how Porsche priced the various models as the end of production neared. In April 1988, for example, a before-options 911 Carrera Coupe (or Targa) Sport was £38,900, and buying the Super Sport model entailed raising £49,240, over £10,000 more. But if you wanted the real thing, the 911 Turbo was £7440 extra.

3.2s, the wide-bodied car feels little different to the standard car. The Turbo chassis upgrades might be noticeable on a fully refreshed car, but otherwise would probably not, while the extra mass of the body doesn’t affect performance in a significant way. Plus, the interior is standard Carrera 3.2 unless the car was optioned up significantly.

However if, like Robin McKenzie of Bedfordshire-based classic Porsche specialist Auto Umbau, you do know your air-cooled Porsches intimately, you might disagree. “They look great, but with 50kg extra weight they don’t feel so good to drive,” he insists.

So you have the well known Porsche Carrera 3.2, with its howling engine, the gearshift that needs careful movements (especially the pre-1986 G50 gearbox), and the unassisted, super-precise steering. The handling is probably best described as mid-career 911: not the wayward, tail-happy original, but still a car that demands a careful right foot, especially in the wet.

The cabin retains most of the early 911 layout, with the much loved, but not entirely visible to the driver, row of instruments, and the tricky to regulate heating system that works off the exhaust heat-exchangers. This era of 911 is the favourite for many 911 fans, who regard it as being better to drive than the early cars, but purer in character and appearance than the final two air-cooled generations, the 964 and 993.

Bodywork

The wider wheel arches of this model have made no difference to corrosion issues, the main areas to examine being the bottom of the windscreen, the tops of the front wings where they meet the scuttle panel, around the headlights and at the petrol filler flap on the front wing. “Open the doors and look at the bottom of the catch plate and sill,” Robin also advises. “Bubbling around the door catch and engine lid release handle means the catch plates, and more than likely the bottoms of the rear wings and the rear ends of the sills, will need replacing.” He reckons rectifying bodywork on this car is a job that’ll go into the tens of thousands in some cases.

Engine and transmission

The engine is the standard 3.2-litre flat-six, so is very reliable, although it does have failings, some easy to fix, others not. “The obvious sign of a poorly engine is it smoking under load, which means the engine is burning oil, and at the minimum a top-end engine rebuild is needed,” says Auto Umbau’s Robin McKenzie. “And one problem that you are unlikely to be able to diagnose is a broken cylinder-head stud. This can only be found with the rocker covers removed.”

If the engine fails to start, it’s likely that the reference and speed sensors have failed. “These suffer from brittle leads and crushed sensors, usually by corrosion from the aluminium bracket, which itself can break and no longer hold the sensors in the right position to be able to sense the flywheel,” Robin explains. Mass air-flow sensors and idle control valves are also known to fail, resulting in rough running.

The standard exhaust system is long lasting but, as it is not stainless steel, it will eventually corrode. Water collects in the back box and rusts through just below the tail pipe. The standard Porsche heat exchangers are prone to rusting and can allow oil fumes into the cabin. “These should be replaced with stainless steel ones – fitting the standard mild steel types is a waste of time, unless the car is being sold shortly,” Robin advises. And replacement is no DIY job, he warns: “Removing them without breaking the studs can only be done by heating up the retaining nut until cherry red, and they can take up to five hours to free up, especially when the heat exchanger flanges are seized into the engine.”

The earlier, 915 gearboxes suffer from a worn and badly set up shift linkage, and this, Robin says, causes people to force the gearstick when changing gear. “The 915 has a longer throw than the G50 ’box, but a well set up 915 is a pleasure to drive, though needs a little bit of time for the oil to warm up. It’s common for the first and second synchromesh rings to wear, and the dog teeth to be broken off.”

Robin says the 915 will certainly be cheaper to rebuild than the G50, which has fewer mechanical issues, but adds: “The G50 gear stick knobs were leather covered and will be pretty grotty by now.”

Suspension, steering and brakes

This is very reliable, with leaking shock absorbers usually the only problem – unless you bash a kerb. The suspension’s robustness can create a problem, though. Robin says, “As a consequence the suspension geometry is often neglected, and the adjusters seize, especially on the rear.”

The plastic bush in the steering column wears out, and replacing this entails removing the gauges and the fresh air inlet box. “So if the steering wheel is wobbly, expect a big bill,” Robin warns.

The brake calipers suffer from brake dust building up under the shims, which in turn stops the brake pad from “floating”. Check that the Fuchs wheels are in good condition. “Many will have been incorrectly refurbished, which is a shame, especially if they have been lacquered, as these will quickly corrode under the lacquer and require refurbishing again,” Robin reveals.

Interior, trim and electrics

The electrics, as Porsche installed them, are mostly trouble free. Dirt builds up on the backing plate of the rear light clusters, which then rust and allow water into the internals, but Robin says this also happens when people over-tighten the lenses and crack them.

However, he pays no tribute to alarm fitters. “They are unlikely to have done a reliable job,’ he complains. ‘We commonly find poor soldering and modules screwed into panels where they have caused damage to the bodywork. LEDs have been drilled into dashboards, and sometimes we find a number of holes from different alarms fitted over the years.”

Porsche 911 Carrera 3.2 Super Sport: our verdict

If there’s not a 911 Carrera Super Sport in your garage, you’ve missed the boat unless you’ve got £100,000 or so lying around. But do you really want one anyway? The truth is that it has the Turbo’s sexy body and its uprated brakes, but fractionally less performance due to the extra weight (although only a few drivers could tell the difference), so in this case, arguably, more is less.

So unless the bulges do it for you, we say settle for a normal Carrera 3.2 and keep a sizeable wad in the bank.