We sample a fan-made replica of the Paris-Dakar-winning Porsche 953 in a Belgian sand pit

Words: Johnny Tipler Photography: Antony Fraser

It’s not hard to see why someone would want to create a replica of the winning Porsche 953 on the 1984 Paris-Dakar rally; Porsche has even taken the iconic machine as inspiration for its latest off-road-biased iteration of the 992-generation 911, the 911 Dakar.

The 1984 race was Porsche’s second attempt on the event, encouraged by Jacky Ickx, the F1 veteran still at the height of his powers in the WEC, helming 956s to claim the Group C Championship crown in 1982 and 1983. So, his aspirations carried considerable weight at Weissach and, having won the Paris-Dakar in a Mercedes G-Wagen in 1983, he had no difficulty convincing the Porsche management to create a team to contest the event. Rothmans, who sponsored the WEC Group C cars would back the Rally-Raid expedition, too, while the 1981 winner, Réne Metge, was also co-opted onto the driver roster. Weissach’s own Roland Kussmaul would helm the back-up car. Historically, Porsche had rallying experience in the Safari Rally in the 70s, so an extreme event like this was not entirely a novel venture.

The 1984 Paris-Dakar was the 6th running of the event, passing through the Sahara, the Ivory Coast, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Mauritania. The Dakar army, 427-vehicles strong, consisted of trucks, motorbikes and cars, all highly modified to deal with the ultimate rigours of a desert crossing and uncharted tropical forested tracks.

The model platform selected for the Dakar was based on the current production 911SC, though there were no homologation issues as the event was not run under the jurisdiction of the sport’s governing body. They could configure it how they liked. For his part, Ickx relished this anarchic aspect, and when I interviewed him at Goodwood 30 years later, he cited the Dakar as a transformative experience, way more up his street than circuit racing. “When I started with Paris-Dakar my vision of the world and the people changed completely,” he said. “That is the most important part of my life, the era when I went to Africa to compete in off-road racing. If you asked me which part of my life I prefer, it’s this one. I discovered the world was much wider than I saw it before, and then really I became somebody different.” I mention this because, again, it demonstrates why a Dakar rep is such a lure.

The 953 was the first example of Porsche’s concerted assault on the Paris-Dakar, which featured the four-wheel drive 959 for the 1985 and 1986 events. Desert racing demanded full-on off-roading capability, so the Weissach SCs were endowed with way more ground clearance than regular rally machines – 27cm, almost 1ft. The front wheels were located by dual lateral arms with twin dampers per side, pre-figuring the 959. At the rear, trailing arms were raided from the 930 Turbo parts bin and clad in plastic, with coil-over dampers and machined CV joints and drilled half-shafts.

In practice, the CV joints boots needed changing several times during the Rally, but the brake pads lasted two-thirds distance – not bad on a 7000-mile event. Dunlop sand tyres were fitted, and apart from five punctures, lasted 5000-miles over supremely arduous terrain. To protect the cars from which, the underside of the floorpan was clad in a carbon-fibre and Kevlar skin, 10mm thick, though lighter than an equivalent aluminium plate would have been. It had a welded-in steel roll cage, and a central tunnel for the front driveline was installed. All suspension pick-up points were reinforced, with the steering box placed inside the front boot due to the high ground clearance. While the glassfibre rear bumper was pierced with cooling slats for the benefit of the oil cooler, the front wings, doors, engine lid and bootlid were in glassfibre, and side windows were Plexiglas with sliding openings. Surprisingly, the standard windscreen was considered tough enough for the event, though the rear screen was a removable panel to give access to the two spare wheels.

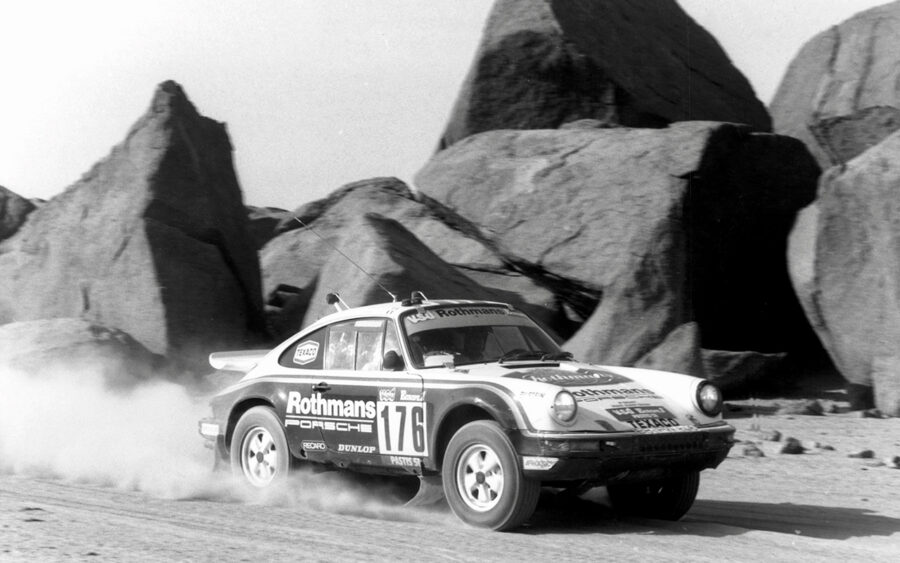

Rene Metge and Dominique Lemoyne in their Porsche 953 at the 1984 Paris-Dakar Rally

A 120-litre (31.7-gallon) fuel tank occupied most of the 953’s front compartment, while a second 150-litre (39.6-gallon) tank lived in the back of the cabin. There was a plumbed-in fire extinguisher system, and a comprehensive tool kit on board including hydraulic jack and electric compressor, plus first-aid kit that included emergency flares and snakebite and scorpion sting serum. Amusingly, when subsequently checking out the Jacky Ickx car #175, mechanics discovered a switch hidden beneath the dash with no obvious purpose.

They traced the wires to the back lights and realised that it was so Ickx could turn off the rear lights so no one could follow him through the dust! Weighing in at a hefty 1210kg, the three 953 SCs were not further burdened with sand ladders, since their approach and departure angles meant they were capable of tackling 45-degree inclines in any case.

Power came from the 3.2-litre 953/84 flat-six, with lower-compression ratio and thus able to function on low-grade fuel. With modified exhaust, power was 225bhp. Economically, it was extremely efficient: Roland Kussmaul’s fuel consumption averaged 18-litres per 100km (13.1mpg) and the winning car of Metge/Lemoyne consumed a mere 5-litres of oil over the Rally’s 11,000kms (7000-miles) duration, whilst running at least part of the time flat out in deep sand.

And sand is what we’ve got here. Our feature car is 2WD, whereas the three Paris-Dakar 953 examples (the two rally cars, #175, #176 plus support car #177) were 4x4s, and the interior of their cabins completely unrecognisable with all the navigation equipment on board. But we can still pretend we’re living the dream. Here’s how that dream panned out, 34 years ago. The Sixth Paris Dakar rally started in Paris on January 1 1984 on a morning so frosty that the bike riders had difficulty keeping their machines upright on the dais. It could only get warmer. Ahead of the 427 entrants was the 1072km run to Sète on the French coast for the Mediterranean crossing to Algiers.

Now the rally proper began: 925km to El Golea, reached late enough in the day to preclude much sleep. The following day a special stage of almost 300km on stony desert caused two punctures on the Ickx-Brasseur 911, costing them 28 minutes, with Roland Kussmaul in the support 953 on hand to assist. The #176 car of René Metge and Dominique Lemoyne also burst a rear tyre on the rocky terrain, compounded by fuelling problems, though they managed 3rd place on this stage.

Next instalment was from In Salah to Tamanrasset, 666km, including 202km of special stage. Some 70km after the start of the stage the Ickx-Lemoyne 953’s dashboard wiring harness caught fire – a wheel jack had broken free and shorted out the cables. It appeared that their rally was over, but its crew, assisted by Kussmaul and two other mechanics, Kieffer and Riley, aboard the 4×4 support truck, managed to fix it up within the time allowed so they could continue. The 5th leg, comprising 588km, of which 270km were special stage, took competitors from Tamanrasset to Iférouane. By now Metge was concerned that the pace of travel over rocks and sand might see his 953 encounter the same malady as Ickx’s wiring loom. The Belgian, meanwhile, was still some four hours behind the leader. However, at the end of this stage the three 953s proved quickest, with Ickx/Brasseur 1st, Metge/Lemoyne 2nd, and Kussmaul/Lerner 4th – with a Lada 3rd quickest. This left Metge/Lemoyne in 1st place in the general classification, followed by the Lada and a bunch of Range Rovers.

The 6th leg took three days to cover, from Iférouane to Chirfa, 1400kms with 559kms of special stage, heading into Niger through the Ténéré desert. Few visual cues regarding direction of travel exist in this inhospitable wilderness, flat to the horizon or traversed by sand dunes. Notwithstanding, the three 911s were clocked doing 180kph in searing heat, and ended up stage winners, with Metge/Lemoyne still topping the table. Averaging 130kph over 617km of the 8th leg from Dirkou to Agadez, the 911 trio once again proved quickest on the stage, with the Ickx car back up to 10th overall. While Metge rolled blithely on over the next stage, the Ickx car had an off, forfeiting three hours.

Controversy surrounded the 10th leg from Niamey to Ouagadougou, 647km, including 464km-worth of special stage, as the Rally-Raid left Niger to enter Burkina. In the middle of a timed special stage, the local authorities decided to prevent competitors reaching the border post. The first crews to arrive forced the issue and got through, but the majority were halted. Eventually the organisers enabled the rally contingent to proceed, and duly cancelled the stage, to the dismay of those who’d made it through in the first place.

Meanwhile, the 953s were readied for the 533km special stage from Ouagadougou to Bouma in the Ivory Coast. The night before, the organisers warned drivers and bikers to watch out when passing through the many villages en route for discarded rusting corrugated iron, tree stumps and other obstacles. That wasn’t what sidelined Kussmaul: his 953 scored a barrel as well as running off the track, while Metge hit a cow and damaged the glassfibre front of the car. Amazingly, they still led the overall standings, with Ickx now up to 8th.

The 12th section from Bouma to Yamoussoukro was 673km, including 328km special stage, over tracks flanked by tropical vegetation, and René Metge moderated his pace a little to avoid another animal encounter. An Opel Manta won the stage, though Metge still led overall, with Ickx 7th and Kussmaul recovered to 8th. Next, 398km from Yamoussoukro to Touba was characterised by dust thrown up by cars traversing the narrow foliage tunnel precluding any overtaking. Nevertheless, Ickx/Lemoyne proved quickest on this stage, with Metge 2nd and Kussmaul 5th. Now the rally entered the Guinea forest, with trees of 4m high, and contestants were exhorted to stop in each village they passed through to ask its name in order not to get lost – though the names changed randomly, there were no credible maps, and no definitive tracks through the forest.

Narrow bridges were made of logs – too slippery for the motorbikes which were obliged to ford the rivers. Undeterred, Metge/Lemoyne kept their lead in the 953, while Ickx/Brasseur moved up to 6th overall. Leg 15 covered 581km from Kissidougou to Freetown, through thinner forest, and then 152km of desert stage, which proved too hot for Metge, whose Porsche was struck by one of the Range Rovers as it tried to overtake. This Solihull vehicle went off the track just 15km from the finish, and though Metge was well out of the running on the stage he still retained the overall lead.

As the event entered its final third, contestants enjoyed a breather in Freetown, capital of Sierra Leone, as well as visiting the Guinean capital, Conakry, on a newly-paved road symbolising the reopening of a previously closed border. From Labe to Tambacounda meant covering 457km through the Senegalese bush, including 221km and 166km of technical special stages on bumpy tracks, accomplished without significant change to the running order. While Ickx won the first stage, Metge took the second, consolidating his place at the top of the table. Then, the penultimate stage from Tambacounda to Sali Portudal led to the white sands of the Senegalese coast, and as Metge/Lemoyne briefly mis-routed, the Kussmaul/Lerner 953 took the stage win, with Ickx/Brasseur close behind.

Finally, the 230km from Sali to Dakar was something of a formality, laid on for the benefit of sponsors who leapfrogged the entire event just to show up at the finish, but still, the ultimate special stage along the beach contained many pitfalls that could wreck everything just a few kilometres from the finish. Ickx/Brasseur kept it together to win the last stage and place 6th overall, while Metge/Lemoyne took the outright win in #176, and Kussmaul/Lerner ended 26th in the support car. There were 92 classified finishers, the remainder abandoned, having succumbed to the rigours of the terrain.

Porsche 953 replica: on the road

So, for our personal reinterpretation of Paris-Dakar 1984, we’ve come to Waterloo, south of Brussels. We usually get lucky with locations for our photoshoots. Sometimes we get really lucky (not by staying up all night, though heaven knows, my colleague tries), and this was one of those occasions. Our old pal Kobus Cantraine is marketing this 911SC, presented as a replica of the ’84 Dakar winning 953, and he’s persuaded the manager of a sand quarry to let us loose in a couple of worked out areas where we can hooley the beast to our hearts’ content.

Our feature car is an American-spec SC. The 3.0-litre engine is unmodified, running US fuel injection, and it even has the air-con compressor – though the exhaust is handmade, specifically so it can exit through the bumper. The air intake is labelled “Webb’s Machine Design, Clearwater, Florida, patent pending”. A retired Californian Porsche fan decided to create a replica of the #176 Metge/Lemoyne car – though he could just as easily have stickered it up as the #175 Ickx/Brasseur car, too. Kobus takes up the story. ‘He took a rust-free Californian SC, stripped it completely back to bare metal and then proceeded to build it up from scratch, modifying the bumpers, creating the suspension, making the roll cage, the winch brackets and the holes in the body. And once he was sure everything fitted he took it all apart and had it painted, and then put it all back together.

The Rothmans logos are stickers but the rest of the livery is painted. As far as we know, he never really used it for anything. It’s got 2000 miles on the speedo since the full rebuild so I think it’s typically the kind of thing somebody gets a kick out of building, and then when it’s done he will sell it, and he’s probably building something else in his garage right now.’ I can’t help thinking that, if he had wanted to go the whole hog and replicate the driveline of the 953 he might have installed that of a 964 C4, and that could be a way for a future owner to complete the reproduction.

As it stands, the beefy suspension consists of Bilstein shocks with Elephant Racing uni-ball rear suspension as used on a 935. The 15in wheels are Group4 replica deep-dish 7in Fuchs, and they have the right offset and look exactly the same as Porsche was using on the 1984 Dakar. It’s running on BFGoodrich tyres, 215/75 R15 front and 235/75 R15 on the back. The engine lid and wing are SC RS, and there’s some weight to it. Under-body protection includes steel skid plates beneath the front pan and along the sills, which cover and protect the oil lines, and there’s also aluminium panelling within the inner front wings cladding the oil lines.

The cabin interior houses a pair of large leather Sparco competition seats, bestowing a classier look to something that the original did not have. The roll cage extends through the car front to back, from engine bay to nose, and within the cabin it consists of diagonal door bars and a tube that sweeps round underneath the dash plus a central bar across the top of the roof and comprehensive triangulated scaffolding in the rear space with a fire extinguisher attached to it. It’s got RS door pulls and wind up windows, and we’ll ignore the Pioneer radio. There’s a fly-off handbrake in chrome with an aluminium top, likewise the gear lever is polished steel with an aluminium top, with alloy pedals and footrest. It’s far removed from the austere environment of the Paris-Dakar 953 because it’s got proper carpets, too. The view through the windscreen is of the regular 911 wing tops and the four humps of the battery of spotlights mounted on the front bonnet. Much as they look the part, none of the contemporary photos from the ’84 Paris-Dakar show these.

The reality check? The 911 configuration works very well in sand, because there’s less weight on the front end so it doesn’t sink in and the engine being in the rear provides more traction. My sideways progress cutting through the sand is aided by the diff-lock which means we don’t get stuck with just one wheel spinning, and that’s good for drifting and ploughing us through the gritty yellow powder. I’m opposite-locking all the time, this way and that, a matter of fine judgement sometimes, and it’s pretty exhilarating and quite breathtaking.

To encourage sideways motion I apply as much throttle as possible and throw the wheel in the other direction to make it jink to one side, and then give it opposite lock and control it on the throttle. A lot of sideways motion is possible through this wonderfully yielding sand and water splashes, pirouetting at will in the vastness of the quarry. It’s some way removed from the Sahara, but it’s also pretty different to off-road rallying, too.

What does the future hold for this fun 911 now? Peking-to-Paris, perhaps, or the East African Classic Safari? Closer to home there’s the MSA British Cross Country Championship, and the classic Roger Albert Clark Rally: you’d get mud rather than sand to cope with, but this Dakar rep could be just the thing.