In the post-Sportomatic era, all Porsche models were equipped with manual gearboxes until to the arrival of the 964 and its Tiptronic system

Words: Shane O’Donoghue

Ready for the 1989 model year, the 964 arrived on the scene with all guns blazing. It was designed to bring the air-cooled 911 — a car seen by many as awkwardly dated — into the modern era, without losing the model’s signature look. The updated design was unashamedly a gentle evolution of the G-series, but underneath, the 964 was mostly new. And, as if anti-lock brakes, coil sprung rear suspension, an automatically deploying rear spoiler, power steering, a unified body and four-wheel drive wasn’t enough, Porsche offered the 964 with the brand’s first ‘proper’ automatic gearbox: Tiptronic.

Some would assign this honour to Porsche’s Sportomatic transmission, but Sportomatic was a manual gearbox with automatic operation of the clutch. It did use a torque converter between the engine and the gearbox, smoothing operation and allowing for stopping when in gear, but Sportomatic didn’t have the capability to automatically change ratios. Nonetheless, despite Sportomatic’s lack of commercial success, it’s said that Porsche’s factory engineers liked the system, and it was the first port of call when they started planning the development of a new automatic gearbox in anticipation of the 964’s launch.

Tellingly, in the early 1980s, several of the manufacturer’s engineers, including Peter op de Beeck, Rainer Wüst, Norbert Stelter and Gerd Bofinger, filed a number of patents relating to clutch control. These respected individuals were clearly in the mindset of using and improving upon the Sportomatic blueprint, but a desire to include five gears caused packaging problems, which would have necessitated a rethinking of the half shafts driving the rear wheels. Around the same time, the dual-clutch Porsche Doppelkupplungsgetriebe (PDK) transmission had been developed for use in endurance racing. The funding for the system was contingent on the technology being made available for Porsche’s road cars.

Consequently, at the start of the decade, a PDK gearbox was installed in a 924 test mule. In 944 prototypes, development of PDK continued, but the project was abandoned, in part due to challenges in making the gearbox work satisfactorily, though primarily due to the cost associated with relatively low-volume production. Porsche almost overcame these frustrations when it looked as though Audi might also make use of PDK, but the Ingolstadt-based brand settled on a then new ZF automatic transmission designed for engines producing high-torque. As luck would have it, the ZF unit was suitable for the transaxle layout of the 911, albeit with a few alterations.

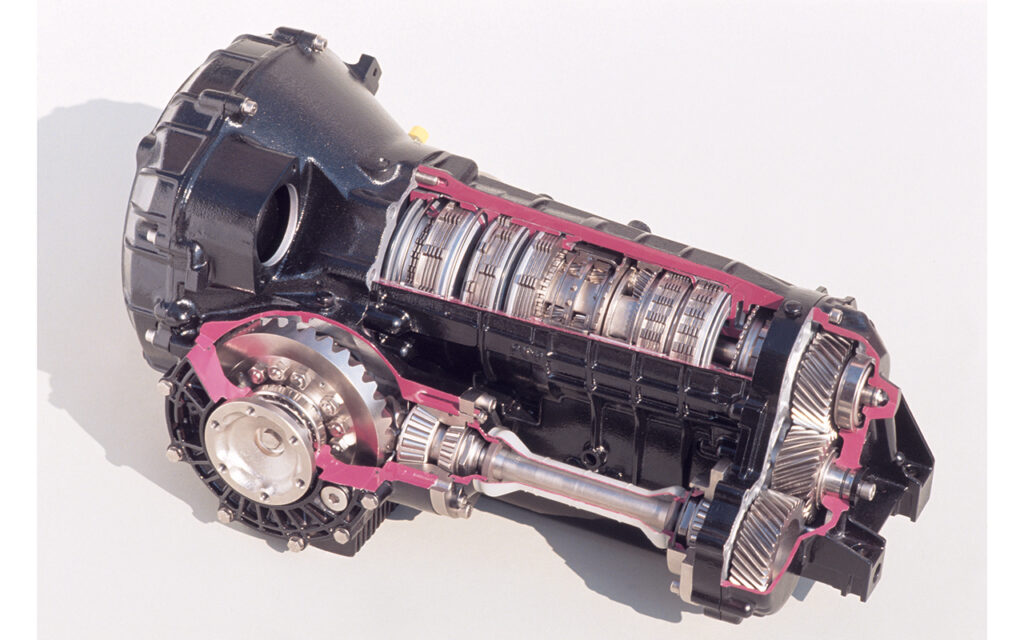

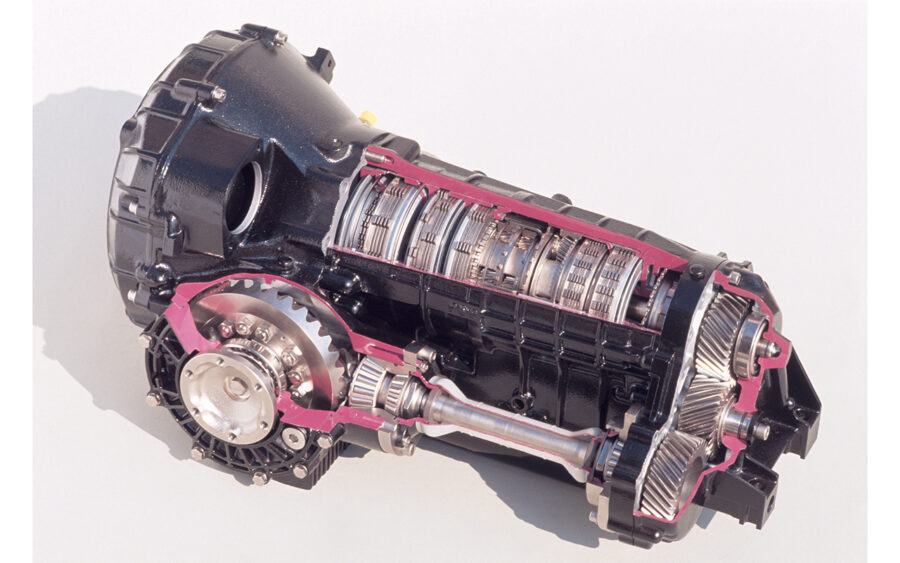

Bolted to the engine’s crankshaft was a torque converter. As explained in last month’s article examining Sportomatic, a basic oil-filled torque converter has a pump (the ‘fan’ turned by the engine), turbine (the ‘fan’ that turns the gearbox) and a stator between them, altering the flow of oil and causing torque multiplication. This is all based on the idea of a fluid coupling, in which there is always slippage. In the Sportomatic gearbox, for instance, there was 3.5% slippage across the torque converter at high speeds, resulting in heat generation in the oil, higher fuel consumption and less direct drive to the road from the engine. The ZF gearbox sought to eliminate these conditions by including a lock-up clutch creating a direct mechanical link between the two sides of the torque converter i.e. joining the crankshaft output to the gearbox input.

In the case of the ZF unit’s installation on the 964, the output shaft turns three helical gears at the front of the gearbox (at the opposite end of the gearbox to the engine), the third of which is connected to an additional shaft. This runs outside the main gearbox casing back to the differential, which then divides up power between the rear wheels. As head-wrecking as it can be to fully understand the internal workings of an automatic gearbox such as this (we don’t have the space to analyse planetary gear and multi-clutch pack workings here, but will do so in a forthcoming issue of 911 & Porsche World), it’s worth noting this wasn’t a new invention for the 964 and, if Porsche had just taken the ZF-produced transmission as it was designed, its introduction in the 911 might be no more than a footnote in history.

Instead, Porsche wanted to do things differently — the Stuttgart concern required the automatic gearbox to adapt its shift strategy to the driver and to allow manual override of the selected gears. Of course, this is the norm today, but back then, it was an innovative idea and, importantly, one much more in keeping with the sporty image of the Porsche brand than adopting an automatic transmission that could just as easily be found in a regular luxury car.

Enabling these new ideas was a separate control computer — these days it would be referred to as a Transmission Control Unit (TCM). Porsche developed this setup with the help of ZF and long-standing OEM parts supplier, Bosch. The cooperation of the latter was crucial to the success of the project, not least because Bosch was responsible for the advanced Motronic electronic engine management system used in the 964. The 964’s TCM used information from the Motronic ECU, the anti-lock braking system and other onboard equipment to calculate which of five different shift strategies to employ at any given moment. Inputs included coolant temperature, engine revs, car speed, throttle position, acceleration and lateral g.

Interestingly, the information flow was bidirectional, allowing TCM to instruct the Motronic system to reduce torque output and engine speed briefly during upshifts, by retarding the ignition, which would have further smoothed out the change in ratio. Also, TCM was configured to prevent shifting when the lateral g sensor showed the car was cornering at more than 0.4g, while a down-change could be initiated by aggressively pressing the accelerator pedal, even without pushing it all the way down to the kickdown switch. Clever as this adaptive shift strategy was, the manual override was more tangible, and it grabbed the limelight for Porsche.

The shift lever moved forward and back in one line from P (Park) at the front, via R (Reverse), N (Neutral) and D (Drive) to manually selectable first, second and third gears. Obviously, the transmission could be left in D most of the time, but the driver could overrule or pre-empt the gearbox’s strategy by sliding the lever into the numbered positions. The control strategy allowed the engine to rev out to the limiter without changing up if used in this manner.

Alongside all this was a new manual mode, selectable from D by pulling the whole lever over to the right into a second, smaller forward-and-back plane running parallel to the main gate. Marked M, the new system featured a little plus sign at the front indicating up-changes, as well as a minus sign at the back for down-shifting. The lever could be ‘tipped’ forward or back as needs be, due to it being spring-loaded to the centre. It’s what set the 964’s Tiptronic gearbox apart from other systems of the era, giving the driver control and engagement when they wanted it, but in conjunction with the ease of use offered by a fully automatic gearbox at other times. As you’ve probably guessed, the movement of the lever is what gave the gearbox its name, though not until after Porsche employed the services of Gotta Brands, a German creative agency known for developing headline-grabbing product names for its clients. Incidentally, the same organisation coined the Panamera model name for Porsche, too.

Oddly, in its initial iteration, Tiptronic’s TCM didn’t allow the engine to sit at its limiter when the driver was using the manual mode. Instead, it changed up automatically. Remarkably, this behaviour remained unaltered until 2007.

More sensibly, Tiptronic didn’t allow a down-change that would cause the engine to over-rev, though it cleverly ‘remembered’ the request for the downshift and made it once the revs dropped. Also, if the driver forgot to change down before coming to a rest, the gearbox automatically selected second gear before taking off again.

The motoring press gave Tiptronic a mildly positive reception, but the four-speed unit became hugely popular with Porsche showroom visitors, accounting for nearly a third of 964 sales in the first few years of production. Tiptronic would also become a popular choice among 968 buyers. This despite the unit’s disadvantages, which weren’t restricted to the fact it cost significantly more to produce than the 964’s manual gearbox and added a whopping thirty kilograms to the overall weight of the host 911. At 159mph, the top speed of the 964 Carrera 2 was only 2mph slower with Tiptronic fitted, but the 0-62mph dash increased from the manual car’s 5.7 seconds to a significantly slower (on paper, at least) 6.6 seconds.

Of course, it took serious skill to extract the manual model’s sprint time and, in truth, in the hands of an average driver, a Tiptronic-equipped 964 was, in real-world terms, no slower. It was, however, a little less economical, but not disastrously so. Nonetheless, for 964s bound for the United States, final drive ratio was eventually raised in a bid to reduce fuel consumption. There’s also evidence of further tweaking of the 964’s Tiptronic transmission during the following years in an effort to enhance its efficiency. It’s worth noting that, though the subject of a fresh feasibility study, Tiptronic was never fitted to the 964 Carrera 4, a proposal dismissed on the grounds of considerable required re-engineering.

Unsurprisingly, the 993 continued to use Tiptronic, though there were a few modifications to the control algorithm: Porsche maximised use of the lock-out clutch for the torque converter and also fed the TCM with data on braking, allowing for the activation of a sporty strategy to down-shift under braking, ready for likely acceleration straight after. A more obvious (and marketable) update was introduced for the 993 in 1995. Named Tiptronic S, it brought in gearchange toggle switches for the steering wheel. Two switches were fitted, one on each of the two upper spokes of the wheel, allowing the driver to change gears with a flick of either thumb. Operation mirrored that of the lever — an up-change was achieved by moving the switch up and down-changes were activated by moving the switch down. At launch, these buttons were activated only when the driver moved the lever into the manual position, and it was still possible to change gears using the lever, if the driver so desired.

This functionality changed when Tiptronic S was fitted to the 986 Boxster, making it necessary to use the steering wheel buttons if you wanted to manually change gears. When the Boxster S was launched in the year 2000, however, the system was updated yet again, this time to allow the driver to override automatic gear selection at any time by pressing one of the buttons on the steering wheel, even without choosing the manual driving mode first. If the driver did nothing else after pressing the button, and the car was not cornering quickly, the gearbox would resume automatic operation after a few seconds.

From its introduction, the Boxster’s Tiptronic setup was the first in a Porsche with five forward gears. Porsche and ZF soon took the opportunity of another round of revisions to improve other aspects of the unit. The lock-out clutch, for example, was no longer just engaged or not — it could be operated in varying degrees of slip. Significant changes were introduced for Tiptronic use in the 996-generation 911, though. Key among the updates was mechanical strengthening and enhanced cooling of the transmission fluid, which was achieved by using the accompanying engine’s coolant circuit.

The 996 Carrera 4 was the first 911 to marry four-wheel drive with Tiptronic. The union was made possible by moving the viscous coupling (which distributed torque to the front wheels) from the front of the gearbox to the differential on the front axle. This development was significant, and though it didn’t mark the end of Tiptronic in Porsche products (it was used to great effect in the Cayenne), the 996’s successor, the 997-generation 911, would wave goodbye to the system in favour of the dual-clutch PDK transmission, prepared for launch in time for the 2009 model year.

PDK may have captured the hearts of Porsche enthusiasts more than Tiptronic ever did, but the newer transmission’s design and engineering was undoubtedly informed by the experience Porsche garnered through the many years of Tiptronic’s evolution, as well as the innovative thinking that went into it.