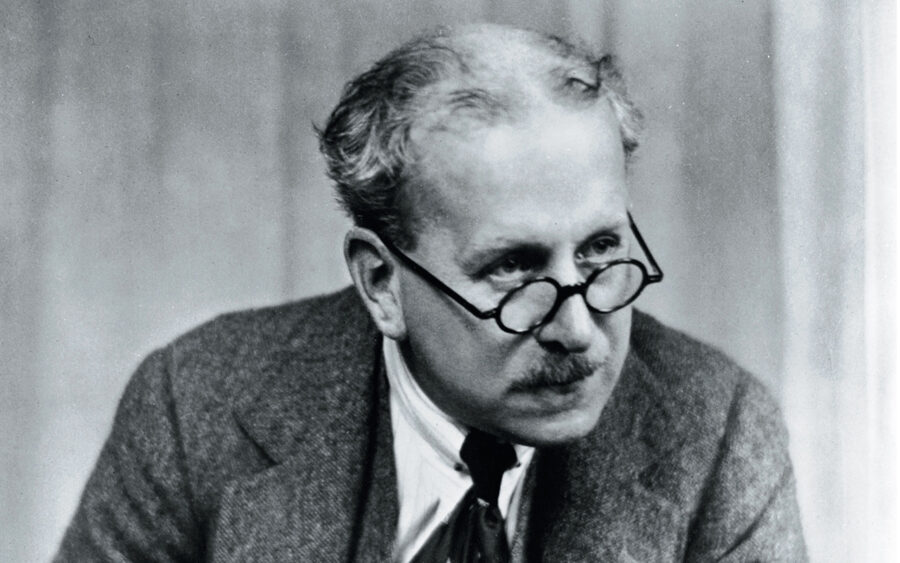

The fledgling company might have floundered had it not been for the diligence and dedication of Claude Johnson, the oft-overlooked businessman who saw himself as ‘the hyphen in Rolls-Royce’

Words: Paul Guinness

Even to those with little knowledge of the motoring world, the names of Charles Rolls and Henry Royce are well-known. They came together to create Rolls-Royce and are guaranteed immortality in the annals of history because of this. But there was a third person in the partnership; the firm’s founding managing director.

Claude Johnson was an astute organiser and business brain, complementing the sales skills and showmanship of Rolls and the engineering expertise of Royce. Content to stay out of the limelight and let others take credit, CJ – as he became universally known at Rolls-Royce – was arguably the most significant member of the trio. His commercial decisions laid the path to prosperity and a reputation for excellence, but it could all have turned out very differently without the man who referred to himself as “the hyphen in Rolls-Royce”.

Claude Goodman Johnson was born on October 24th 1864 in Datchet, then part of Buckinghamshire. The village is just across the River Thames from Windsor, making it a rather appropriate location for CJ to emerge into the world, given how closely associated the family with the big house over the water would become with the marque Johnson would much later be responsible for.

The Johnson clan was a large one; father William and mother Sophia had four other sons (Leslie, Douglas, Norman and Basil) and two daughters (Mildred and Evelyn). This severely tested finances, which William Johnson’s job in the glove trade couldn’t really cover. He eventually got a job within the science and art department at London’s South Kensington Museum (now the V&A) and relocated his household to Ealing.

This obviously improved the family’s fortunes, for the young Claude Johnson was sent to the well-respected St Paul’s School and then moved on to South Kensington’s Royal College of Art. His father, who had grown into a renowned art expert thanks to his museum role, no doubt had a hand in this; but once there, Johnson discovered that his artistic talents were minimal.

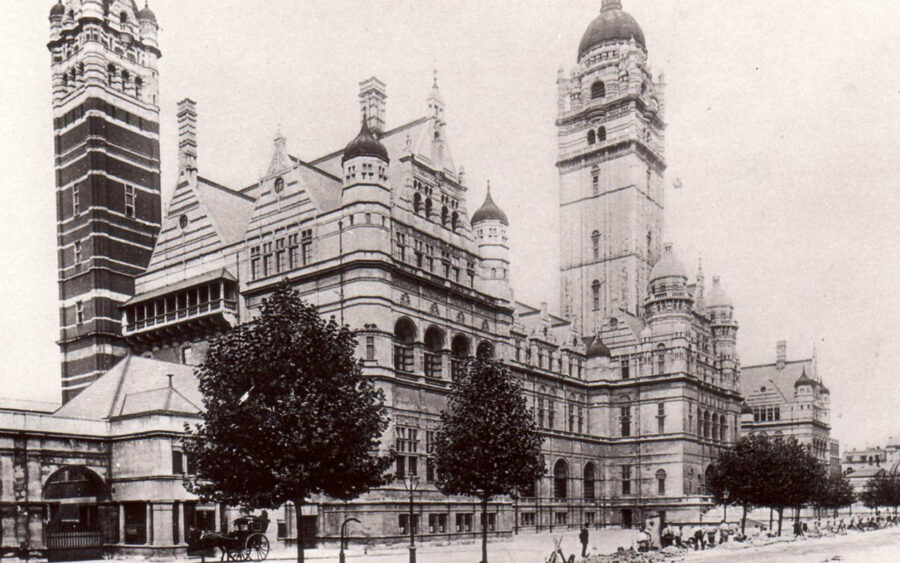

The Imperial Institute, where Claude Johnson honed his organisational skills, was next door to the South Kensington Museum where his father worked.

He did, however, meet Sir Philip Cuncliffe-Owen, the assistant director of the South Kensington Museum, who nurtured his organisational abilities instead and was instrumental in securing him his first job in 1883, as a 19-year-old clerk at the Imperial Institute. Soon afterwards, he eloped with a local Ealing girl, Fanny Morrieson, and got married, against the wishes of his parents. The two went on to have eight children, but only one – a daughter – survived childhood. Some have attributed Johnson’s hard work ethic to this great personal sorrow; he threw himself into jobs as solace from an unhappy home life.

At the Imperial Institute, Johnson’s responsibilities included organising exhibitions that showcased the British Empire, which first brought him into contact with Royalty, meeting Queen Victoria and Edward, Prince of Wales. The latter was fascinated by the new-fangled automobile and in 1896 pressed CJ, who’d swiftly risen to become the chief clerk of the institute, to organise an international exhibition of motor vehicles. This also gave the Prince of Wales the handy excuse for his first ride in a car, something that CJ made possible.

The event ran from May 9th until August 8th and by the end of the three months of being surrounded by these latest inventions, CJ also had a profound interest in them. Indeed, when the Red Flag Act (which dictated that all self-propelled road vehicles should travel at no more than 4mph, with somebody holding a red flag walking in front) was repealed in November of the same year, Johnson was one of those who turned out to participate in the celebratory run from London to Brighton. Granted, he only had the luxury of a bicycle with which to follow the horseless carriages, but seeing as the speed limit had only been raised to 12mph, he probably didn’t have to struggle too hard to keep up.

The Imperial Institute exhibition had brought Johnson to the attention of Frederick R Simms, founder of the Motor Car Club behind that first London to Brighton run. Simms had become dissatisfied with his original organisation and wanted to start afresh. In 1897, he did just that, with the Automobile Club of Great Britain (which would later metamorphose into the Royal Automobile Club). A secretary was needed, and Simms offered the position to Johnson in November. His recompense for leaving the Imperial Institute was £5 per week – a not untidy sum back then – with the added bonus of ten shillings for every new member signed up. At that point, there were just 163 of them.

CJ’s destiny was now set; the newly-converted petrolhead was suddenly in charge of the day-to-day running of the organisation established to promote the motor car in Britain. However, just a year later he was ready to resign, dismayed at what he perceived as a lack of interest in both cars and the club itself. The committee convinced him to stay and, by the start of 1899, membership had risen to 380.

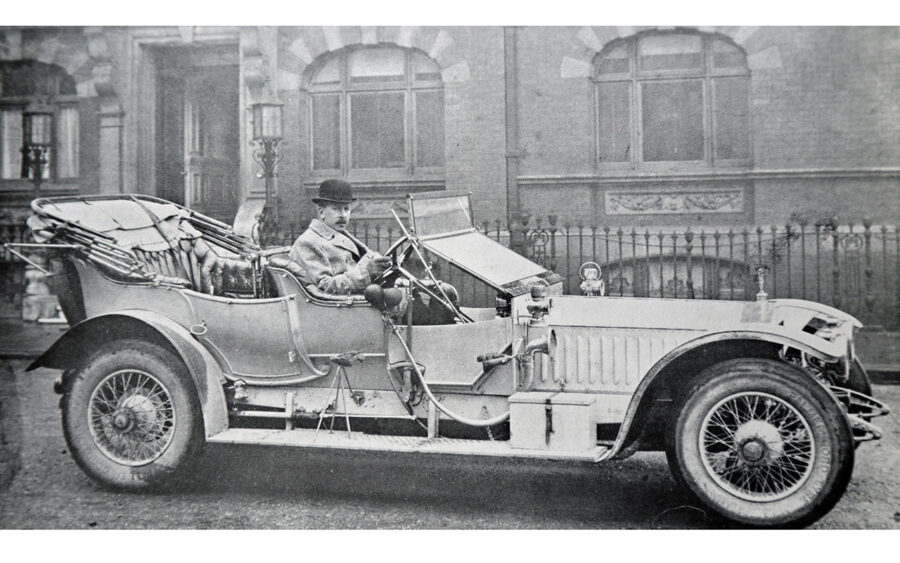

The second Phantom ever built, with Claude Johnson at the wheel.

During the summer of that year, Johnson organised another car show, this time in Richmond Park, closely followed by the club’s first trials, at which electric vehicles proved themselves rather more adept than the petrol ones, albeit over limited distances. However, Johnson’s usual flair for planning seems to have deserted him slightly, as the show and the trials left the club with an enormous loss of £1500. Even to this day, it’s not clear quite how such a staggering deficit was incurred.

That put CJ’s next scheme – a 1000-mile trial across Britain – in doubt, but a friend and fellow club member came to his rescue. Alfred Harmsworth was a publishing magnate with a string of newspapers and magazines, including the Daily Mail with circulation in the hundreds of thousands. He promised widespread publicity for the trial, and this convinced the club’s committee to back it. Johnson planned out the route himself using a borrowed Panhard and Daimler. The route went from London to Bristol, and then north via major cities to Edinburgh before returning to London by an alternative route. The total distance was 1060 miles.

The 1900 1000-mile trial of the Automobile Club of Great Britain and Ireland, to give it its formal title, then took place between St George’s Day on April 23rd and May 12th. A gold medal went to a certain Charles Stewart Rolls driving a 12hp Panhard, which managed to hit a blistering 42mph. Hot on his heels was William Exe, who netted the silver medal in a 6hp Daimler. The mysterious Mr Exe was none other than Johnson himself, masquerading under a pseudonym, perhaps to deflect attention from any unfair advantage he might have had as the architect of the route. Nowadays, the Daily Mail would have no doubt delighted in exposing such subterfuge. That Johnson’s – sorry, Exe’s – top speed was 27mph shows just how impressive Rolls’ performance was.

More trials followed, as did a suggestion from CJ that cars should carry number plates so that police could identify them more easily. While there was a burgeoning public interest in the motor car, there was also considerable hostility thanks to speeding incidents and traumatised horses, which still represented the main form of road transport. Even Johnson himself was found guilty of “furious driving and refusing to stop” and fined £20 with £11 14s costs during 1901. Evidence does suggest, however, that the normally very careful driver was made an example of by over-zealous authorities.

In 1903, Johnson resigned as the secretary of the Automobile Club, having seen its membership rise to over 2000. Three men had to be appointed to fulfil his duties; a mark of how much pressure and responsibility had been increasingly heaped upon him. His wife had finally given birth to a healthy daughter, Elizabeth, which probably also influenced his decision. Home life was suddenly a lot happier. He joined the City and Suburban Electric Car Project, but his stay there lasted only a few months before he was lured away by Charles Rolls to help run his car showroom and workshops in London.

Charles Rolls and Henry Royce; the former died in 1910 and the latter fell gravely ill soon afterwards, leaving CJ to run Rolls-Royce.

The two worked well together. The aristocratic Rolls was one of the UK’s most prominent motorists and a competent engineer with plenty of money and contacts in high places, while Johnson was a superb organiser and business mind. However, the two found themselves selling foreign makes such as Panhard et Levassor and Minerva because they were more advanced than British machines of the time. Rolls in particular harboured a desire to build a British car that could compete with the best of the sophisticated European marques.

That opportunity came when Rolls was introduced to Henry Royce in April 1904. Royce, a very brilliant and intuitive engineer, was building his own cars in Manchester, albeit based on a Decauville design that he’d extensively improved. When Rolls got back to London after his trip up north, he told CJ that he had “found the greatest engineer in the world”. All the bits of the jigsaw were falling into place. Johnson was also impressed with the 10hp Royce car when he saw it, and the firm of C.S. Rolls and Co entered into an agreement with Royce Limited to sell the car.

There was one important proviso; the name would change to Rolls-Royce. The arrangement was that Royce would build the chassis and Rolls would be responsible for the body, via London coachbuilder Barker’s, with the range expanding to include 15hp three-cylinder, 20hp four-cylinder and 30hp six-cylinder models.

A new company – Rolls-Royce Limited – was founded in March 1906, with CJ running it. All the other marques that Rolls had been selling were dropped by the end of the year. CJ made sure that publicity for the new company’s products remained high, from trials and international shows to more prosaic demonstrations, such as proving that a 30hp Rolls-Royce wasn’t too large to turn in a London street.

Johnson won the £10 bet by personally managing to swing the leviathan around in just 32 feet. At London’s November 1906 Motor Show, a new and expansive 40/50 chassis debuted, which proved so popular that CJ took the risky decision to focus just on this vehicle and drop all other models.

The 40/50 became known as the best car in the world thanks to its extraordinarily high standards of engineering.

It turned out to be the right decision, and Rolls-Royce found itself with more orders than it could fulfil. It was obvious that a new factory was needed and Johnson eventually settled on Derby, lured by the prospect of a readily available cheap workforce (thanks to the railway workshops there) and the city corporation offering to lay on gas, water and electricity at very reasonable rates. To raise cash for the new plant, Rolls-Royce issued £100,000 of shares to the public and Johnson formally became general managing director.

Claude Johnson decided to make the twelfth 40/50 model something special, so it could be used as a demonstration and promotional vehicle. The April 1907 chassis was fitted with Barker four-seater open touring bodywork finished in aluminium paint with silver-plated fittings. Johnson himself christened it The Silver Ghost, with a plaque proclaiming its title on the scuttle. The name would soon become unofficially associated with all 40/50s, which the press had also labelled “the best car in the world”. There was, however, only one true Silver Ghost – AX 201 – and CJ was the man behind its creation.

The new Derby factory was opened by Lord Montagu of Beaulieu on July 9th 1908. It all seemed to be going very nicely for Rolls-Royce but then Charles Rolls, whose interest in cars had waned somewhat when he took up flying, was killed in a plane crash in July 1910, aged just 31. He was the first British person to die in a powered aircraft accident. CJ and Royce vowed to carry on without him, with Johnson’s next significant move being to commission a mascot exclusive to Rolls-Royce. He’d become concerned about the appropriateness of some of the radiator adornments he’d seen on the firm’s vehicles and thus asked Charles Sykes to come up with something more suitable. The Spirit of Speed figurine, designed by artist Charles Sykes and modelled for by Lord Montagu’s secretary and mistress Eleanor Thornton was unveiled in February 1911, becoming known as The Spirit of Ecstasy soon afterwards.

Years of very hard work caught up with Henry Royce at around the same time, as his health seriously deteriorated, the situation inevitably being exacerbated by stress from the death of Rolls. Doctors gave him just three months to live, but Claude Johnson arranged for him to recuperate in Norfolk and then, when well enough to travel, in the south of France where Johnson owned a villa in Le Canadel. He bought the adjacent land to enable Royce to have his own home in a much kinder climate. This was soon joined by a third building, complete with a design office, so Rolls-Royce engineers could work with the sick technical genius. It must have been quite a contrast to industrial Derby.

Royce eventually became well enough to split his time between France, Kent and Sussex but never went back to Derby. This effectively left Claude Johnson as the only one of Rolls-Royce’s founders to still have day-to-day input into the running of the company. He also had a new wife following the death of his first one. Evelyn was affectionately referred to by her husband as Mrs Wigs, with Joan, their daughter, known as Tinks. It seemed a much happier relationship than his first marriage.

It was Claude Johnson who commissioned the Spirit of Ecstasy mascot, as a response to what he regarded as very inappropriate ‘comic’ figurines.

Rolls-Royce continued to be successful, finding customers among the more well-heeled of society and international royalty. But in August 1914, the First World War broke out and the company had to set aside luxury to concentrate on vital military work. Instead of decadent machines, 40/50s started to be produced with armoured car bodies, and Derby also expanded into aircraft engines, designed by Royce. CJ adopted the policy of naming them after birds of prey, dubbing the first three types the Eagle, Hawk and Falcon. By the end of hostilities, Rolls-Royce had become the world’s largest aero engine manufacturer.

Immediately post-war, a lot of Johnson’s time was taken up by trying to establish an American division, Rolls-Royce of America Incorporated, in Springfield, Massachusetts. It resulted in him having to make many tiring trips to the USA, with his brother Basil serving as acting managing director in the UK while he was abroad. He also realised that the 40/50 model was getting long in the tooth and so asked Royce to come up with a new, smaller 20hp car. His admiration for his colleague remained undiminished; when Claude Johnson was offered a knighthood in recognition of Rolls-Royce’s wartime efforts, he declined and recommended it go to Royce instead.

The Rolls-Royce Twenty was launched in 1922, with the 40/50 being upgraded to four-wheel brakes soon afterwards and then being superseded by the New Phantom in 1925. By contrast, Johnson’s personal cars were a Ford shooting brake and small Morris Cowley, the latter chosen because it “will do well for shopping rather than the new Ford one-ton ambulance”, as CJ referred to the Blue Oval estate.

The strain of the many trips to the United States took its toll on Johnson and he went into 1926 feeling unwell and losing weight, but still working as hard as ever. On April 6th, he attended his niece’s wedding in Buckinghamshire but felt so ill there that daughter Elizabeth rushed him back to London by car to see a doctor. A severe bout of pneumonia was diagnosed and CJ died on April 11th. His brother Basil – whose daughter’s wedding it had been – succeeded him as managing director, but it was still a monumental and shocking loss. Henry Royce probably summed it up best by saying: “He was the captain and we were only the crew”.

Claude Johnson’s ashes were scattered, with little ceremony, in Golders Green Crematorium’s Garden of Remembrance, but a more notable memorial was put up in the form of an arcade at the Derby works. The tablet there contained the words of CJ’s friend, Rudyard Kipling: “He had the imagination to foresee and the energy to meet the needs of his country both on land and in the air, and his ideals were reflected in all his work”.