We take an in-depth look at the Rolls-Royce Corniche – the elegant two-door saloon and convertible flagship model that went on to enjoy a famously lengthy career

Words: Richard Gunn

Up until the arrival of the Silver Shadow and its T-series sibling, Rolls-Royce’s separate chassis construction meant there was always the option of coachbuilt bodywork. Even though the increasing adoption of the monocoque process by the British car industry had resulted in a drastic reduction in the number of traditional coachbuilders, there were still some customers who wanted something more than the ‘Standard Steel’ bodies that Rolls-Royce offered as, well, standard.

With the Silver Cloud, this was still easily achievable because the bodyshell sat on a chassis rather than being integral to it. However, when Rolls-Royce entered the modern world with 1965’s Silver Shadow, finally moving over to monocoque construction, it seemed the end for special-bodied models aside from ultra-exclusive Phantom V. Fortunately though, that proved to not quite be the case; soon, both Rolls-Royce itself and one of the few remaining specialist coachbuilders, James Young, proved that variations on the Silver Shadow theme were both possible and desirable. We’re talking, of course, about the two-door saloon and convertibles that later evolved into the Corniche and Continental models.

There had once been a multitude of different coachbuilders providing bespoke bodywork for Rolls-Royce buyers. By the mid-1960s, however, only two main players remained. The company had its own specialist – Mulliner Park Ward – which had been formed in 1961 when Rolls-Royce amalgamated the two in-house names of H.J. Mulliner & Co and Park Ward. The two old-established firms had been acquired in 1959 and 1939 respectively. Then there was James Young, owned by the Jack Barclay dealership, that had been around for over a century.

It was, perhaps surprisingly, James Young that was the first to succeed in going beyond the four-door Silver Shadow. It managed to come up with a two-door variant within months of the October 1965 launch of the regular saloon at the Paris Motor Show. It was a swift turnaround, although the changes made were relatively simplistic, with longer passenger doors taking up some of the space that had been previously occupied by rear doors, and the B-pillars relocated a few inches further back. Aside from some wood and leather alterations inside, the most radical stylistic flair was the elongated door handles.

While the model was a brave attempt by James Young, all buyers really got for their extra £1214 was something that still looked very Shadow-esque but was rather less practical. Only fifty – 35 Rolls-Royces and 15 Bentleys – would be sold up until 1967, with James Young going out of business one year after that.

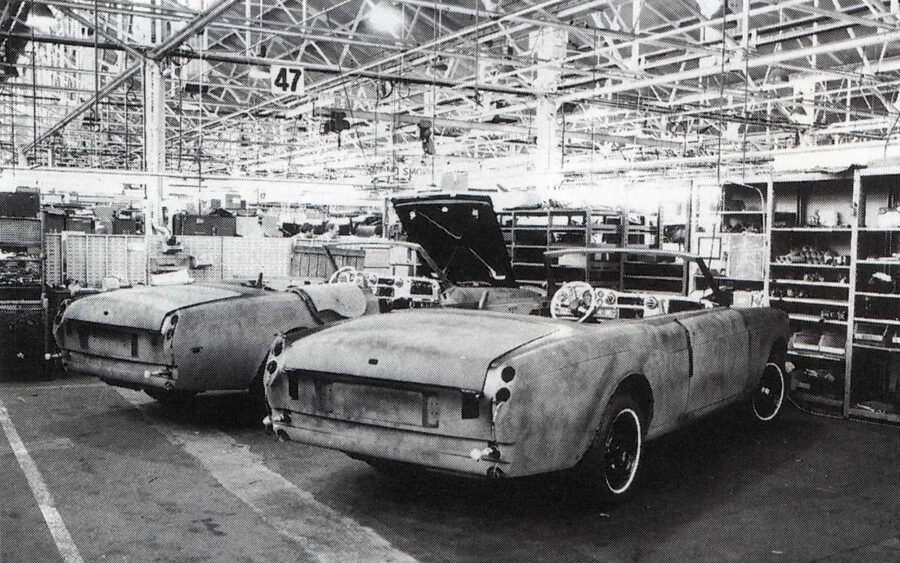

By contrast, Mulliner Park Ward took some time to create something considerably more bespoke, although it also had access to far greater resources than James Young, which had to buy its cars complete and then convert them. Being a part of Rolls-Royce meant that MPW had underpan, scuttle and bulkhead Shadow assemblies delivered by body builder Pressed Steel to its plant in Willesden, London, to which more individualistic coachwork could then be added. That came courtesy of Rolls-Royce’s chief designer John Blatchley and his deputy Bill Allen, who penned a two-door design that, while clearly derived from the Silver Shadow, also had enough stylistic flourishes to make it stand out. Most notable was the ‘Coke bottle’ kink to the rear wings, discussed in more detail further on.

The Silver Shadow was already a modern-looking machine for the mid-1960s. But what was officially called, rather ponderously, the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow Mulliner Park Ward Two-Door Saloon (and its Bentley T-series sister) looked even more contemporary and up-to-date when unveiled at the March 1966 Geneva Motor Show. The ‘official’ cars cost £380 more than the James Young efforts – at £8150 for the Rolls-Royce and £8100 for the Bentley – but they were better-looking and arguably better-built, shuttling between MPW’s Willesden factory and Crewe, using a labour-intensive, hand-crafted build process that took around twenty weeks – eight weeks longer than for a standard saloon.

The success of the MPW Two-Door Saloons effectively sounded the death knell for the James Young cars. They also guaranteed further development of the MPW model. This manifested itself in October 1967 in the form of the Drophead Coupe version, with extra underbody strengthening and a power-operated hood that met Rolls-Royce’s demanding standards. This alone took a week to install and perfect during the build, illustrating just what a quality piece of work it was. Naturally, there was a further price premium for such luxurious al fresco motoring, with the Rolls-Royce costing £8550 and the Bentley £8500.

A policy was soon introduced for the two-door cars, which saw them receiving some major improvements ahead of the four-door saloons. While the more cynical might see this as a form of development testing on customers – something British Leyland would also indulge in – it did also mean that those buying the two-door models got upgrades quite a way ahead of four-door customers. For example, the new GM400 automatic gearbox went into the MPW cars several months ahead of its fitment elsewhere in 1968, while air conditioning was standardised in spring 1969 – just in time for summer – and didn’t filter down to the other cars until the end of the year. In the years to come, enhanced brakes, sharper suspension and cruise control would all pop up first on what would be renamed the Corniche.

The MPW Two-Door Saloons and Drophead Coupes officially changed their name in March 1971, in the midst of difficult days for Rolls-Royce. There was a desire to differentiate the cars even further from their Silver Shadow and T-series saloon siblings, and the Corniche name was already one in the company dictionary, having been used for a 1939 one-off streamlined Bentley. It was also rather more evocative than ‘Project Gamma’, the internal designation for the rechristening. To be fair, the Corniche – a name applied to both the Rolls-Royces and Bentleys – was more than just a different moniker, as it also offered 10% more power from its V8 engine (giving an estimated 220bhp), a reworked interior with more wood, a deeper radiator grille and different wheel trims.

When the Silver Shadow II and T2 saloons appeared in 1977, their rubber-faced shock-absorbing bumpers, front air dam, flared wheelarches, rack-and-pinion steering and tweaked suspension were also fitted to the Corniche. This did not result in a name change to Corniche II though, something of a labelling inconsistency. Even when the rear suspension from the almost imminent Silver Spirit was fitted during 1979, it wasn’t enough to prompt an alteration in the Corniche’s designation.

That only happened in 1986, when the Corniche II was formally launched – although only for the United States, the rest of the world having to content itself with the original moniker for another two years. By that time, the Corniche saloons were no more, having been discontinued in March 1981. But the convertibles remained in production, despite some stillborn plans to develop a new open-top Rolls-Royce based on a lengthened Silver Spirit platform.

The Corniche II wasn’t really that much of a significant progression. Aesthetically, it could be distinguished by colour-coded bumpers and door mirrors, plus yet another redesign of the wheel trims. Anti-lock brakes were also new – and needed – and the seats were improved. The big news was on the Bentley front, however, a marque that was enjoying something of a revival, emerging from the shadow of its Rolls-Royce parent thanks to the introduction of turbocharged models elsewhere. Clearly delineating the two marques was paying dividends with sales, and although there were no thoughts (yet) of turbocharging the convertibles, reviving the great Continental name and applying it to the Bentley-badged variants added a useful degree of separation, as did the fitment of a new dashboard with separate round instruments.

Having introduced the Corniche II and relaunched the Continental nameplate, Rolls-Royce seemed to find new enthusiasm for christening parties, with the Corniche III making its debut just a few years later in 1990. This time the wheel trims were ditched for good and alloy wheels fitted in their place. Bosch MK-Motronic fuel-injection now fed the engine and the suspension was given electronic aids. Inside, the dashboard, console and seats were tweaked, and air bags added – and there was also now the option of a CD player, for real audio advancement. The Continental got the same upgrades, but without any name change.

Within two years, Rolls-Royce was playing with names again. 1992’s Corniche IV saw yet more suspension upgrades via the Silver Spirit’s adaptive ride set-up, and the old GM400 three-speed transmission progressed to a four-speed GM4L80 unit. The front passenger now also had an airbag (as well as the driver) and the soft-top mechanism was improved – it no longer needed to be manually latched. It also had the benefit of a heated rear window, as the screen had been changed from plastic to glass.

With the Corniche by then celebrating its 21st birthday (even though, technically, the overall convertible design dated from 1967 and had thus survived a quarter of a century), there was a special anniversary edition finished in Ming Blue with a cream hood and magnolia upholstery. The driver’s door housed a vanity set, the while the passenger door had a cocktail cabinets. Only 25 were built – which rather suggests Rolls-Royce might have been subtly acknowledging 25 years of the convertible after all – although only 22 escaped into the public domain, as that most notable of Rolls-Royce aficionados, the Sultan of Brunei, snapped up three of the £165,271 cars.

In 1994, Rolls-Royce closed down Mulliner Park Ward’s Willesden factory, which meant that Corniche (and Continental) production was taken fully in-house at Crewe. By then, however, the model’s days were numbered. Having been designed almost thirty years previously, it had enjoyed a long run by any standards – particularly for a car competing in the upper echelons of the luxury market. Even with its increasingly frequent updates, the Corniche was clearly a 1960s car in a 1990s world.

In the summer of 1995, the Corniche line finally came to an end. But it went out with a bang, in the form of 25 Corniche S models with turbocharged V8 engines, complementing the eight Bentley Continental Turbos that had previously been built. These had proved that the cars were capable of handling the 300bhp-plus that turbocharging made possible.

That the Corniche was able to so long outlast the Silver Shadow it was based upon is a mark of just how effective its styling was. Upgrading a car mechanically (and electronically) is one thing – and the Corniche received plenty of under-the-skin enhancements to keep it on a par with its contemporaries. But managing to create something that looked so elegant and fresh in the mid-1960s, and yet could still cut it in the mid-1990s, had been a much more difficult trick to pull off – and it’s a credit to its designer, Bill Allen, that he managed it. Even if he was somewhat surprised himself: “Having retired in 1977, it astonished me to discover that this car had almost reached its 25th anniversary in 1993 and some were still being sold,” he said. Others were probably somewhat less amazed.

Infamously, the Corniche model was launched at a time when Rolls-Royce was in terrible financial trouble, with genuine concerns that the company wouldn’t survive. It chose to relaunch its two-door cars in March 1971, just a month after what has now become known as Black Thursday, 4th February. It was on that day that Rolls-Royce became Britain’s biggest post-war bankruptcy and was forced to call in the receiver, putting the livelihood of 84,000 employees at risk.

It wasn’t, however, the car division that was in strife; in fact, it was doing quite nicely thanks to the Silver Shadow. However, over on the aero engine side – a field where Rolls-Royce had become the largest manufacturer in Europe during the decades since it built its first ones during the First World War – things were far from rosy.

In 1968, the conglomerate was awarded the contract to provide the engines for Lockheed’s L-1011 TriStar airliners. What it came up with was the innovative and advanced RB211 turbofan engine. However, there was a wide gulf between what Rolls-Royce had promised, and what it could deliver. Development costs had doubled to £170.3m by September 1970, and it was estimated that it would cost much more to make each engine than the £230,375 they could be sold for. By January 1971, the haemorrhaging of money had become all too much, and Rolls-Royce declared insolvency.

Because of the importance of both Rolls-Royce and the RB211 project, Edward Heath’s Conservative government effectively stepped in with nationalisation, with Rolls-Royce (1971) Ltd created in May to acquire the old concern’s assets and renegotiate contracts. It was right in the middle of all this crisis and chaos that the Corniche emerged. Journalists must have been a little surprised at being flown to Nice in the south of France for the launch by a company with so little spare cash.

For the car division, what all this meant – aside from real uncertainty as to what the future held – was the creation in April of Rolls-Royce Motors Limited. This acquired the assets of the car, diesel engine and coachbuilding (Mulliner Park Ward) in June, giving some security to its 8166 staff. In May 1973, just over two and a quarter years after Black Thursday, Rolls-Royce Motors was sold off for £33 million – and with privatisation, its future became more assured.

Rolls-Royce was rarely ahead of the curve when it came to styling, generally preferring to tread the path of traditionalism. And that was how its customers generally liked it; there was enough controversy when the Silver Cloud switched to quad headlamps. However, with its Silver Shadow successor, Rolls-Royce did begin to reflect modern, contemporary styling and the two-door cars took that even further – even helping, it could be argued, to set a trend. It was all most un-Crewe-like.

Although the basic shape of the Silver Shadow was retained with the two-door Mulliner Park Ward cars that evolved into the Corniche, there was one very noticeable styling distinction that marked them out from the crowd: the Coke bottle ‘flick’. Basically, this was a pronounced kink and upwards kick to the rear wing that disrupted what might otherwise be very slab-sided styling. It was influenced by the fighter jets of the day, which incorporated it as an aerodynamic aid; but on vehicles, it was much more about visual appeal rather than any performance advantage. The resemblance to Coca-Cola’s distinctively tapered glass bottle was what earned the look its nickname – although it was also known as the wasp waist, and even one of Hollywood’s greatest goddesses got a look in, with ‘the Marilyn Monroe shape’ also being used as an early label.

Rolls-Royce wasn’t the first to incorporate Coke bottle styling; it was the Raymond Loewy-designed Studebaker Avanti over in the USA that launched the look on cars, in 1962. But that opened the floodgates; Buick followed suit with its 1963 Riviera and Chevrolet did similar on its Corvette Sting Ray of the same year. By the mid-1960s, the touch was becoming so widespread over the Atlantic that even Britain had to sit up and take notice.

While it was Rolls-Royce’s chief designer, John Blatchley, who had penned the Silver Shadow, it was his deputy, Bill Allen, who came up with the Coke bottle rear flanks on the two-door cars. While it’s probable that some of his influence came from what was emerging in America – a big market for Rolls-Royce – the styling did also echo that of the old Bentley S-Type Continentals, with the hint of a separate rear wing.

When the MPW two-door saloons came out in 1966, they were among the first British cars with the Coke bottle look. Vauxhall may have just slipped in ahead with the Cresta PC of 1965, but soon there would also be the Viva HB and Victor FD, Aston Martin would weigh in with the DBS, and Ford would later field the Escort MkI and Cortina MkIII. Then came the Hillman Avenger, Sunbeam Alpine and Rapier, Triumph Stag.

That it was so ahead of the field helped the two-door Rolls-Royces and Bentleys, in both closed and convertible form, to stay looking crisp and current through to the late 1970s and early 80s, when more angular styling became dominant once more. Even after that, the Corniche continued to age more gracefully than most.