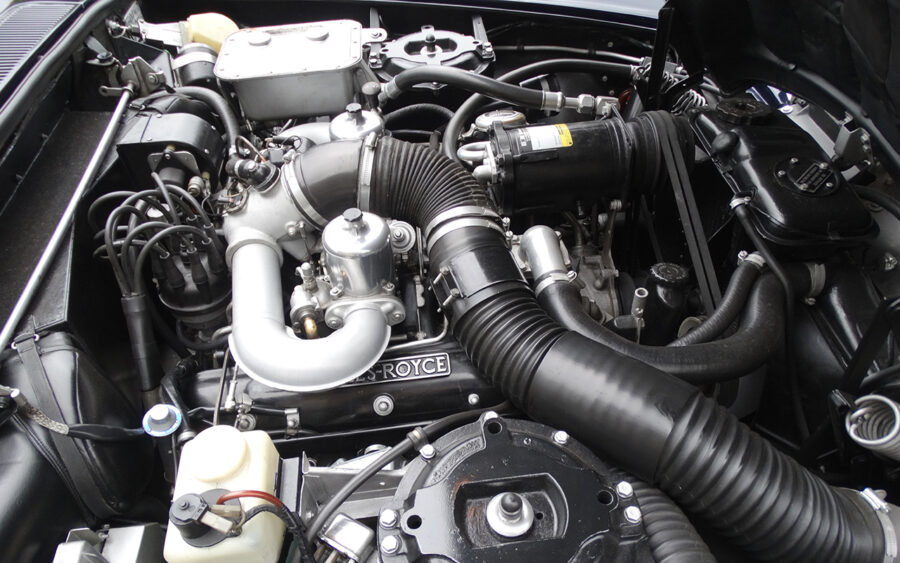

The famous Rolls-Royce V8 was a cornerstone of the British car industry for more that sixty years. Here’s what made it so special

Words: Paul Guinness

The classic L-series V8 engine – originally introduced by Rolls-Royce in 1959 – bowed out of service in 2020 with a run of just thirty examples of the Mulsanne 6.75 Edition; with the end of the Mulsanne came the end of the engine that has powered the vast majority of Rolls-Royces and Bentleys for more than 60 years.

The L-series V8 that began its career powering the Silver Cloud II and Bentley S2 models ended up as the longest-lived powerplant still used in a production car – an impressive feat by any standards. But when you also consider that today’s lustiest version of the classic L-series pushes out a mighty 530bhp (plus 811lb.ft. of torque), making this turbocharged behemoth more than 2.6 times as powerful as its forebear of 1959, you begin to realise what a special engine it is – one that has undergone the most astonishing levels of development and re-engineering over the years.

Although the original 6230cc V8-equipped Silver Cloud’s output of 200bhp doesn’t sound particularly impressive by today’s standards, let’s not forget that its power-to-weight ratio was world-beating by standards of the late ’50s. It was also a highly advanced design, with a two-plane crank, silicon-aluminium block, short stroke and over square dimensions. Indeed, much of its design principle was guided by Rolls-Royce’s previous experience with V12 aero engines.

Rolls-Royce’s then chief engineer, Harry Grylls, stipulated that “the bearing surfaces should be large enough to allow a 20 per cent increase in power and torque over its lifetime”. That was forward-thinking, of course, although it makes you wonder what Grylls – who died in 1983 – would have made of the L-series in its latest incarnation.

By 1965, the L-series V8’s output (although officially described by Rolls-Royce simply as ‘adequate’) had edged up to 225bhp, and four years later its capacity grew to 6.75 litres by increasing the stroke. In six-and-three-quarter guise, the L-series V8 went on to power every subsequent Rolls-Royce and Bentley (until more recent years), with a major change coming in 1980 via the introduction of Bosch K-Jetronic fuel-injection in order to help meet emissions regulations.

The L Series first appeared in 1959, powering the Silver Cloud II and Bentley S2

A bigger upgrade arrived in 1982, however, when the first Mulsanne Turbo was launched, bringing back to life the concept of the ‘blown’ Bentley. With 300bhp (and 442lb.ft. of torque) available, this latest version of the L-series V8 used a Solex downdraught carburettor in a sealed box pressurised by a single turbo. The better-handling Turbo R then followed, complete with fuel injection and an additional 20bhp and 44lb.ft. Power increased again in 1994 (this time to 355bhp), and yet again in 1998 with the adoption of Zytek injection and an intercooler to give the Continental R engine 419bhp.

For a short period in the late 1990s, the venerable V8 was being assembled by Cosworth, but production shifted back to Crewe following the acquisition of Bentley by Volkswagen. The launch of the Silver Seraph and Bentley Arnage in 1998 saw BMW engines (V12 and V8 respectively) replace the long-running L-series in the company’s four-door line-up, although the Bentley Azure and subsequent new-generation Rolls-Royce Corniche continued to use the ubiquitous British-built V8. By the start of 2003, Rolls-Royce found itself under BMW stewardship, bringing to an end the marque’s long-running involvement with the L-series engine.

Bentley, meanwhile, introduced an updated management system and twin Mitsubishi turbos to replace the Garret T3s, raising power and torque of the L-series to 500bhp and 737lb ft respectively by 2007. But just four years later, the engine was completely re-engineered – more than half a century on from its original launch. Although Bentley had considered introducing V8, W12 and W16 engines from elsewhere within the Volkswagen empire, with development work starting as early as 2006, it was discovered that none could deliver the lazy, low-revving characteristics of Crewe’s own twin-turbo V8. Simon Atkinson, module leader of chassis power train at the time, told me: “The V8 delivers that relaxed feeling in a unique way. Because it’s a high-capacity engine and only eight cylinders, we have a very big piston face that helps to deliver a large amount of torque combined with a long, 99.06mm crank throw.”

Atkinson went on to explain that the engineering team wanted to achieve three fundamental targets from re-engineering the existing powerplant: “One, emissions regulations and the company’s commitment to reducing CO2 by 15% by 2012. Two, because it’s the halo product, Bentley wanted a very refined engine, which the old one wasn’t particularly. And three, we needed to reduce weight across the engine in order to aid refinement and CO2 and to offset some of the car’s additional features.”

In the end, the only aspects of the engine that remain unchanged were the headline power figures of 752lb ft of torque at just 1750rpm and 505bhp at 4200rpm. Working closely with specialist engineers Grainger & Worrall and using the latest FEA block casting techniques, a weight saving of 7.7lb was achieved. Likewise, the cylinder heads were redesigned to integrate secondary air rails injecting extra air into the exhaust stream, creating an additional burn that lit off the catalysts more rapidly.

The first-generation Bentley Azure employed a 385bhp turbocharged version of the venerable V8

Other weight saving measures included five-ounce lighter pistons, three-ounce lighter con-rods and a significant 30lb reduction in the crank assembly, partially achieved by incorporating a 0.8-inch axial hole but also by eliminating sludge traps designed to capture oil debris in the days before synthetic lubricants.

A Hilite International cam phaser operating through 47 degrees managed to improve CO2 emissions and fuel consumption at idle and low engine speeds, whilst developing more torque at higher engine speeds. But the big advance in fuel economy (now up to 16.7mpg over the EU combined cycle) was the introduction of a variable displacement system that shuts down two outboard and two inboard cylinders under specific conditions, effectively turning the engine into a V4 firing on A1, B3, B2 and A4 cylinders.

Simon Atkinson explained more at the time of that latest development: “The engine has a central camshaft that drives the tappet or lash adjuster, with a push rod driving a rocker arm to open and closes the valves. On the variable displacement system we’ve introduced a new tappet arrangement controlled by an electrically-driven solenoid, which de-latches a couple of pins and slides within itself, thereby no longer passing the motion of the camshaft onto valves – and so the valves stay closed whilst the camshaft rotates.”

By cutting fuel to the remaining cylinders and closing the valves, it effectively turned those pistons into air springs, compressing the air on the upward stroke and expanding it on the way back down to return the energy. The twin turbos maintained the same rotational speed as if all eight cylinders were operating, however, ensuring instant response when the driver stepped back on the throttle.

The engine was given another lease of life in 2014, with a redesigned top end to match the improvements made to the bottom end in 2011. Direct injection was considered at the time, which could have resulted in a further power increase and extra efficiency, but this would have been at the cost of increased particulate emissions, hence Bentley’s decision to stick with MPI.

The Mulsanne 6.75 Edition is the last ever car to be powered by the long-running V8. The Mulsanne itself was first introduced in 2010

The piston crown and inlet port combustion chamber were redesigned to increase tumble and to propagate faster combustion without incurring knock, with CFD techniques making sure the airflow into the cylinder was very controlled. The offset spark plugs were moved to a more central location, with the latest 12mm long reach versions being used together with Bosch EV14 injectors to promote a lower droplet size for a better spray pattern.

There was a 16% reduction in valve train friction by re-profiling the cams to allow valve control with lower spring forces – about 30% on the intake side and 10% on the exhaust, resulting in a 16% reduction in friction. And because of that reduction in energy, lighter sodium-filled valves were used.

Knowledge gained from the cylinder-deactivation programme helped to improve the company’s software strategy, thereby reducing the penalty incurred during the transient mode between V4 and V8 configurations. This helped to generate the 811lb ft torque figure mentioned at the start of this feature, plus a mighty 530bhp: “We haven’t hit the transmissions limit yet,” claimed head of powertrain engineering, Paul Williams, at the time. Despite such figures, there was a 15% reduction in CO2 and an improvement in fuel economy to 20mpg on the EU cycle, although owners could expect even more. “We’re very proud that in real life you get better than you achieve on the cycle,” said Williams.

Fast-forward to 2020 and it’s finally the end of the road for the venerable L-series V8. The engine that spent six decades powering some of the world’s most impressive – and most expensive – saloons, coupés, convertibles and limousines is finally bowing out after a record-breaking career. It leaves behind, however, an impressive array of classics that will continue to be powered by the L-series for many years to come. The L-series V8 may be about to die but its legacy will live forever.