Its now over 70 years since Jaguar introduced both the XK120 fixedhead coupe and the SE model, cars that set the standard for future models

Words: Paul Walton

There was nothing clever or cryptic about the name Jaguar gave its new variant of XK120 in 1951, because SE literally meant Special Equipment. However, considering the higher specification the package offered, what it lacked in creativity it made up for with accuracy. Together with the more refined fixedhead coupe version that had arrived earlier the same year, the pair transformed the XK120 from a simple sports car into something more refined, the kind of car for which the company would later become synonymous. No example exemplifies this as successfully as the final one produced in 1954 and no owner was as suited to the car as its first.

By all accounts, Alex Henshaw was a genuine British hero, the sort that boys would have read about during the Forties and Fifties in The Hotspur or Eagle comics. Born in Peterborough on 7 November 1912, he learnt to fly at the Skegness and East Lincolnshire Aero Club in 1932. Although funded by his wealthy father (who later bought his son a de Havilland Gypsy Moth), Henshaw Jnr was clearly a natural in the air, soon making a name for himself in racing. In 1933, he competed in the Kings Cup Air Race, taking the event’s prestigious Siddeley Trophy. After winning the inaugural London-to-Isle of Man air race in 1937, he turned his attention to long-distance flying and, in 1938, flew from Gravesend to Cape Town and back. The four days, ten hours and 16 minutes he took to cover the 12,754-mile round trip was a new record, which lasted for 70 years.

At the start of World War Two, Henshaw began working for Vickers-Armstrong and, after testing Wellington bombers at Weybridge, he was invited to work with Spitfires at Southampton. He moved to Castle Bromwich in 1940 and was soon appointed chief test pilot. It’s said that Henshaw flew ten percent of all the famed fighter planes produced, flying up to 20 aircraft a day, often in foggy conditions. He would also demonstrate the planes for visiting dignitaries, including the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, in 1941.

The immediate post-war years saw Henshaw become a director of Miles Aircraft in South Africa before returning to England in 1948 to take charge of the family farm and other business interests in Lincolnshire. In 1953, he was awarded the Queen’s Commendation for Bravery for his rescue work during the dreadful floods that afflicted the county earlier that year.

It’s clear from the car Henshaw bought in 1954 that the now-wealthy former fight plane test pilot hadn’t lost his love of speed because it wasn’t a luxury saloon he chose, rather an XK120 in SE spec, which offered more refinement than a standard roadster could offer. It was also the very last fixedhead coupe ever produced.

Jaguar had introduced the FHC at the Geneva motor show four years previously, and offered everything the OTS did in terms of performance (in fact, due to having better aerodynamics, the coupe was slightly faster), but was much more civilised. Not only did it offer the benefit of proper weather protection, but it also had conventional exterior door handles, wind-up glass windows that could be lowered completely, and opening front quarter lights for better ventilation, all luxuries that were rarely fitted to sports cars at the time, including the XK120 roadster.

The new roofline was similar to that of the one-off SS 100 coupe from 1938, but most of the bodywork was the same as the OTS except for the front wing-mounted air vents that could be opened inside. They provided good airflow to counteract the heat generated in the cockpit (a feature that was also standardised on the open car at around the same time). The FHC’s doors were slightly wider to improve access and the windscreen surround became an integral part of the bodywork with the roof.

Arguably, though, the biggest change over the open two-seater was to the coupe’s interior. More luxurious, instead of leather as per the roadster, the centre console – which also featured a new layout of switches and dials taken from the Mk VII – was covered in thick walnut veneer, as were the door tops. There was even a lockable glovebox and two recessed interior lights adjacent to the rear window.

The XK120 fixedhead coupe was well received by the press. “When it is realised that this car, capable of speeds in excess of 120mph, coupled with startling acceleration, has a basic price of £1,140, some idea of its exceptional value for money will be gained,” reported Autocar magazine in its 17 October 1952, issue. “This fact, coupled with the built-in ability to withstand a great deal of hard work without protest makes it a very desirable car.”

That opened up a new, more civilised market compared to the basic OTS and is regarded as Jaguar’s first genuine Grand Tourer, a position that was further consolidated by the introduction of the Special Equipment model the same year.

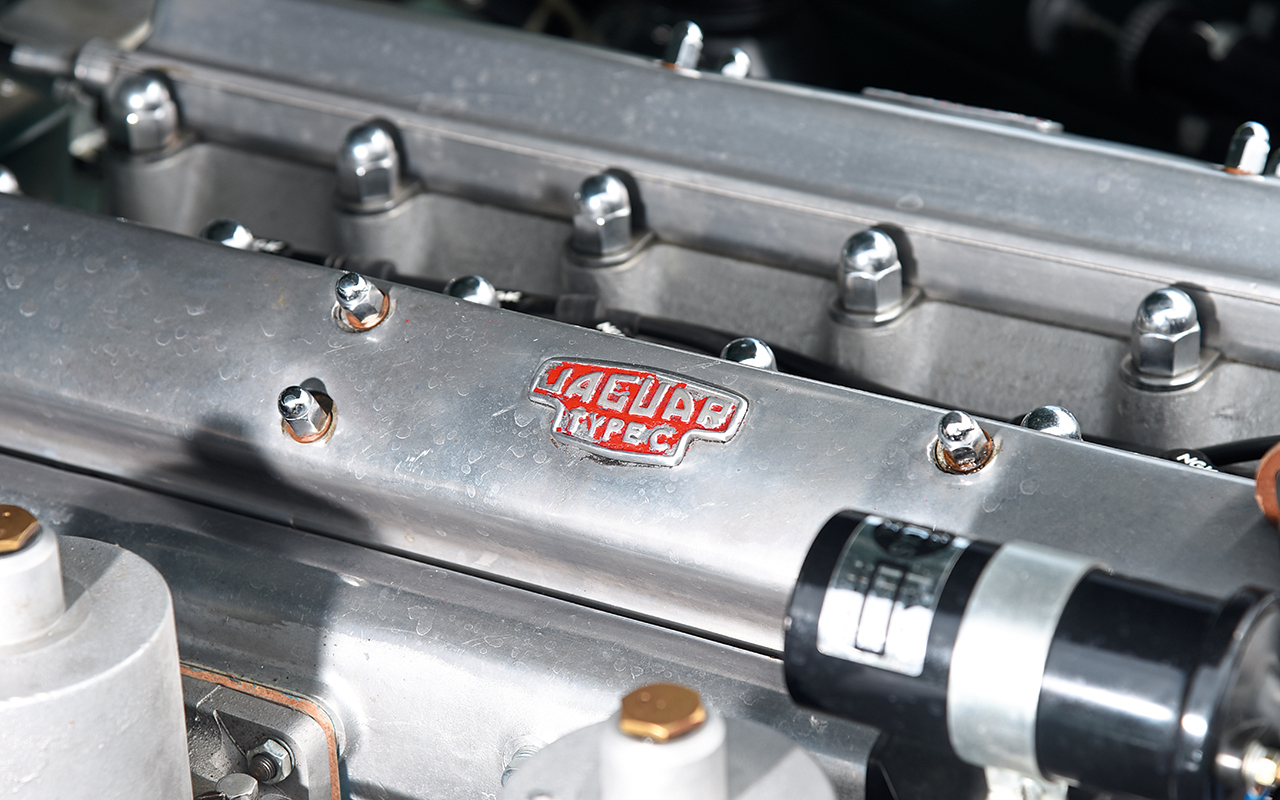

It could be ordered new from the factory and, using information learned by success on the track, the SE package consisted of high-lift camshafts, a special crankshaft damper, lightened flywheel, 8:1 compression ratio pistons and a twin exhaust system. Autocar magazine discovered that in this trim the XK120 FHC could manage 60mph in 9.9 seconds (more than two faster than it had earlier achieved in a standard roadster) and on the long, arrow-straight Belgian motorway between Ostend and Jabbeke it was able to reach the magic 120mph. “The fact that there is sufficient power available to propel this car at such a speed gives it superb acceleration,” continued Autocar, “a quality that makes it extremely pleasant to drive and enables long distances to be covered very quickly.”

Together with stiffer springs and wire wheels in body colour, the SE spec was good value, costing a mere £115 for the roadster and £105 for the FHC. With its increased refinement, the coupe and the faster SE spec was a highly desirable combination and, even in 1954, the final year of XK120 production, it made the then-elderly car still popular with more discerning buyers.

They included Alex Henshaw who bought the final FHC through his local Jaguar dealer, Roland C Bellamy, in Grimsby. Registered GJL 300 and painted in Suede Green with matching interior trim, chassis number S669195 was built on 14 July 1954, coming off the Browns Lane production line a few months before the final open two-seater in September.

Perhaps a result of Jaguar’s involvement with aircraft during the war (including manufacturing components for the Spitfire), but somehow Henshaw had a personal relationship with the company because he was able to specify the optional SU 2in carburettors with a coarse, sandblast finish, which no other XK120 had been fitted with from new. Correspondence with his family by the current owner shows that Henshaw, who passed away in 2007, apparently visited Browns Lane with his FHC just three months after taking delivery, insisting that it be retrofitted with the C-type head.

Available from April 1953, the special head was based on that used for the race-winning car: the inlet valve size remained at 1 3/4in, but the exhaust valve diameter increased from 1 7/16in to 1 5/8in. Both the inlet and exhaust porting was enlarged so that, in conjunction with 8:1 pistons and two 1 3/4in carbs, when fitted with the C-type head the 3.4-litre unit was rated at 210bhp, 30bhp more than the standard engine.

Henshaw only kept the XK120 for two years, selling it on to Richard Colton, a well-known Ferrari collector and amateur racer, who went on to compete in the car throughout the country. Sir George Burton, the chairman of Fisons Ltd, a British pharmaceutical, scientific instruments and horticultural chemicals company based in Ipswich, later took ownership of the car. Burton was another motor sport enthusiast who once raced Frazer Nashes at Brooklands and twice entered the Monte Carlo Rally in the Fifties.

It’s not known how or why, but by the late Eighties the XK120 was in a poor state and stored in a draughty barn. Thankfully, an unknown saviour commissioned the respected classic car expert Nigel Dawes to restore it. On completion in May 1997, the green coupe went overseas to a Californian-based collector and was only occasionally seen, such as at prestigious events like Pebble Beach.

The Jaguar came back to the UK in 2007, after its current owner bought the car via auction. Once again, the XK120 is set to change hands as it is for sale through Manor Classics, located a few miles outside York in the gorgeous North Yorkshire countryside – which is where you find me heading to on this gorgeous July day.

Whether it’s the last E-type, XJS or XKR, there’s always something special about the final example of any car. Following constant development, it should be the best example built, so GJL 300 (Henshaw’s original number, reissued soon after the car’s 2007 return to the UK) represents the ultimate closed XK120.

It’s certainly a pretty one. Designed as per the open car by Jaguar’s founder, Sir William Lyons, the XK120 fixedhead coupe is an early example of his eye for both perfect proportions and stylish details. And, although the restoration is almost 25 years old, the car’s condition remains immaculate, the rich Suede Green paint being the perfect match for the soft, voluptuous curves that Lyons was renowned for.

The interior is a huge improvement over the austerity of the XK120 roadster. Boasting more thick veneer than the Duke of Westminster’s TV cabinet, its luxury is more on a par with the Mk VII. However, the FHC can’t compete with the saloon on space. With the top of the doorframe being lower than the roofline and the huge steering wheel hindering ingress, climbing inside is complicated. Plus, once inside there’s even less room and visibility, due to the tiny front, rear and side windows (the latter so low I need to stoop to see out), is poorer than that from a third-class cabin of a transatlantic cruise ship. But the classic white-on-black Smiths dials inset into the polished veneer, together with the simple Bakelite and chrome controls that typify the era, make the interior as beautiful as a finely crafted piece of furniture. It might be tight but it’s not a terrible place to be.

The coupe weighs a very light 1,370kg, so the sweet and free-revving nature of the XK unit, especially when fitted with the C-type head, provides surprisingly eager acceleration for a car that was built when smoking was considered healthy. Although the Moss four-speed ’box can be tricky to get right without grating the gears, power arrives sooner and a little easier than in a standard XK120, the XK engine’s familiar gruff growl echoing around the snug cabin when it does.

The unassisted steering isn’t just light, it’s also accurate. So although the huge diameter of the steering wheel makes me feel like I could be at the helm of a pre-war steamer ship, with practice I’m still able to effectively carve through the tight Yorkshire roads.

Even in SE trim like this, by the time Henshaw bought the then six-year-old XK120 it would have felt old-fashioned compared to newer models from Jaguar’s continental rivals, including the Alfa Romeo Giulietta Sprint and Mercedes-Benz 190 SL. Yet, although this was the last example, I can imagine the still handsome coupe, with its extra power, fulfilled the then-grounded Henshaw’s continuing need for speed. Special Equipment might not have been a clever name, but it remains the perfect way to describe this fabulous car.