The turbocharger transformed Bentley’s sales and image in the 1980s and 1990s, a process that began with the Mulsanne Turbo

Words: Paul Wager

“Simply massive” was how Autocar summed up the Bentley Mulsanne Turbo in its first road test of this unlikely new performance hero back in 1982. And it’s a phrase that neatly sums up the entire vehicle: simple, massive… but with an almighty kick that back then hadn’t previously been found in a saloon of such size. It may have started out as a not-entirely-serious side project but once developed into a production model, the appeal of the go-faster Mulsanne and the subsequent Turbo R effectively created an entirely new market segment. More than that though, it single-handedly ensured the revival of the long-sidelined Bentley marque, to the point where it would eventually become a desirable prize for the top German car makers.

Given the cost of designing all-new luxury saloons from scratch, it came as no surprise to find that the new Bentley Mulsanne of 1980 was little more than a badge-engineered version of that year’s Rolls-Royce Silver Spirit. Both cars employed what’s known as Rolls-Royce’s SZ platform, which was closely derived from the older SY platform that had underpinned the Silver Shadow since 1965 – and it was this that had effectively limited Bentley to the status of sidekick.

Despite its prestige and brand appeal, Rolls-Royce in the early 1970s was in a financially precarious state. February ’71 had seen the parent company collapse following difficulties with the development of the RB211 aero engine. The car division’s profitability was unaffected despite production being temporarily halted, and it was eventually hived off in 1973 as Rolls-Royce Motors. At this point it was free of any financial issues surrounding the Rolls-Royce aero engine business, but was instantly relegated to a tiny player with slender resources, competing in an arena with well-funded opponents like Daimler-Benz, BMW and even Cadillac.

This meant that a replacement for the Silver Shadow couldn’t be a clean-sheet design, as resources didn’t stretch to the budgets required. Fortunately though, despite its ageing looks, the Silver Shadow had been a very modern design at launch, which meant its platform still had plenty of life left in it. The brief from the boardroom was that the replacement car should look more contemporary, but could the engineers please, please try to incorporate as much of the Silver Shadow’s lower body as possible, while also carrying over the drivetrain.

The carry-over running gear was the easy part of the task, since Rolls-Royce and Bentley customers cared rather less about overhead camshafts, multiple valves and electronic engine controls than buyers of more workaday cars. After all, they weren’t bragging to their colleagues about the ‘GL’ badge on their boot lid, and indeed hoped never to open the bonnet. This meant the long-serving L-Series V8 could continue in its traditional ‘six-and-three-quarters’ capacity, complete with carburation courtesy of SU. The power traditionally described as ‘adequate’ was fed via GM’s Turbo-Hydramatic three-speed gearbox to a rear axle carried on suspension inherited from the later Silver Shadow.

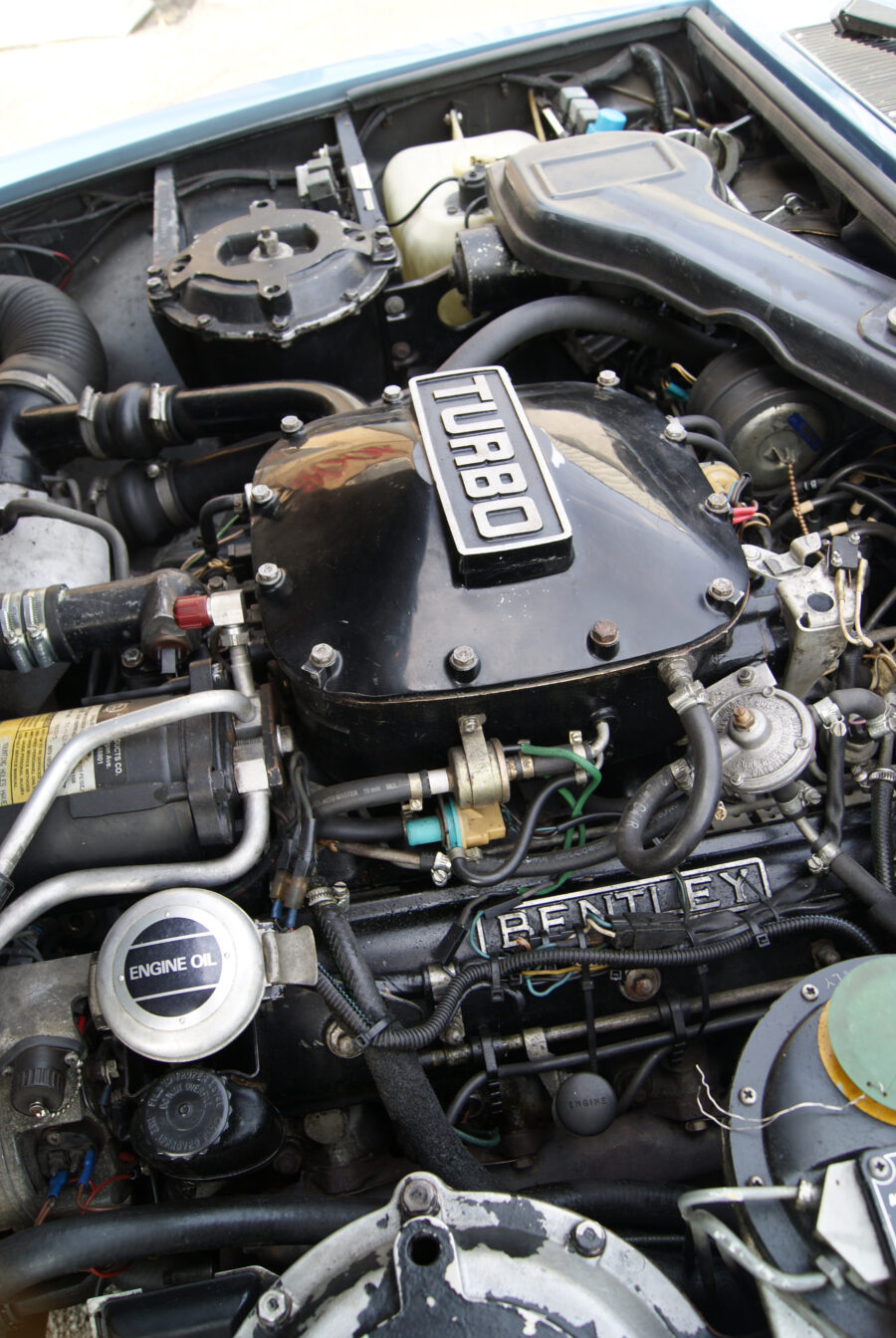

Turbocharged L-Series V8 in the Bentley Mulsanne Turbo

This had, however, been improved with the addition of what was called internally a Refinement Package, designed to answer criticism of the Silver Shadow’s handling by redesigning the angle of the rear trailing arm pivots to allow a greater degree of camber change as the wheel moved up and down. This also raised the roll centre of the car, which reduced body roll and provided a flatter ride. The rear track was also widened by three inches, the result being much-improved handling and ride comfort as well as reduced tyre wear.

Interestingly, this redesigned rear suspension was trialled first on the lower-volume Corniche and Camargue models, but was never fitted to the Silver Shadow. No doubt in order to keep up with the astonishing ride comfort and handling balance offered by Jaguar with its cheaper XJ-derived models, the Silver Spirit also introduced a reinforced rear subframe to carry the rear axle and suspension, now mounted to the bodyshell with isolating rubber mounts.

The self-levelling system from the Silver Shadow was carried over, with the Girling set-up using the dampers as a height control mechanism, a valve controlling the flow of fluid from the car’s high-pressure hydraulic system. Using the dampers as struts in this way removed the need for separate height control rams and so freed up more boot space.

The styling, however, was a much harder task, given the constraints of the ‘SY’ platform. Making the car look more modern was the easy part, as in the all-important US market the Rolls-Royce models were physically smaller than the land yachts from Lincoln and Cadillac. The task was entrusted to in-house stylist Fritz Feller, who used clever detailing and styling tricks to make the new car appear much larger than its predecessor, despite being only marginally longer and wider. This was achieved mainly through enlarging the glass area by some 30 per cent and lowering the roofline by half an inch, while a more horizontal design for front and rear lights gave the illusion of a wider car.

The newcomers were unveiled at the 1980 British International Motor Show, with Rolls-Royce and Bentley models being virtually identical aside from the radiator grille and some very minor detailing. At this stage, the choice between the two brands was largely down to how ostentatious buyers wanted to be, the less flamboyant grille being pretty much the Bentley’s sole selling point.

Bentley Mulsanne Turbo

Development

It’s widely assumed that development of the Turbo began as a means of differentiating the Mulsanne from the Silver Spirit, but in fact work started a decade before the wraps came off the new car. Marque historians report that it was back in 1973 that Rolls-Royce Motors’ managing director, David Plastow, approached engineering chief John Hollings with an idea that now seems remarkably forward-thinking. With an eye to the future, he wanted to invest in preparing the company to embrace new technology. After all, Rolls-Royce was still relying on SU carburettors while high-end competitors like Mercedes were already producing models with fuel-injection… and US emissions regulations were only going to get tougher.

One of these ideas was turbocharging, which was a brave move indeed; back then, BMW’s 2002 Turbo had yet to be unveiled, meaning there wasn’t a single turbocharged production car on the European market. Undeterred by Hollings’ reluctance and encouraging him with words along the lines of “Oh come on, let’s have some fun”, Plastow procured a tired Silver Shadow development car and sent it off to the motorsport supremos at Broadspeed.

Plastow reportedly didn’t even give Broadspeed a budget, and when the car was returned six months later it came with a bill for £7000 – a hefty sum in 1973. Reports from the time suggest the installation was crude but effective, the car lacking in refinement but being brutally quick in a straight line. Considering the development prototype was a slightly shabby Silver Shadow, piloting it would have been a memorable experience.

With the basics sorted by Broadspeed, Rolls-Royce took the project in-house and quickly began gaining expertise in the science of turbocharging. The design was evolved with eventual production in mind, with the team concentrating on such areas as refinement and underbonnet heat. A second prototype was created in 1977 using a pre-production Camargue, and at this stage it was realised that the original installation with the twin-SU carburettors wouldn’t flow sufficient air; a four-barrel Solex was therefore used instead, as already found on the Camargue and Corniche. Sadly, the fuel-injected engine developed for US-market cars couldn’t satisfy both the fuelling requirements of the forced-induction engine and the emissions requirements of the more restrictive export markets, meaning any turbocharged model couldn’t initially be sold in Australia, Japan or North America.

In its final production form, the new engine boasted some 50% more power than the normally-aspirated V8, something which was only revealed when new regulations in the German market required the peak power figures to be published. Crewe had traditionally been coy about numbers, merely stating that power output was ‘adequate’. Official figures, however, revealed that the turbocharged V8 produced 298bhp at 3000rpm compared with the regular version’s 199bhp.

Even at this point the firm still fought shy of revealing torque figures, which was perhaps a shame since the monstrous twist was really the key to the car’s sledgehammer performance, with the 2234kg saloon now cracking 60mph in just seven seconds in the hands of Autocar magazine, topping out at 142mph. For comparison, the regular Mulsanne posted figures of ten seconds and 129mph.

The new car was launched as the Bentley Mulsanne Turbo at the Geneva Motor Show in 1982, the package consisting of the turbocharged drivetrain, a discreet Turbo plaque on the bootlid, a body-coloured grille surround and… that was it. The mighty Citroën-inspired high-pressure brakes with their four front calipers had stopping power in reserve for the uprated engine, so needed no upgrading… but the suspension was a different matter. With the springs and dampers unchanged from the regular Mulsanne and Silver Spirit, the Turbo was stunningly quick in a straight line, but road testers of the day were alarmed by its handling.

With a kerb weight of 2.2 tonnes, a high centre of gravity and the potential to arrive into corners rather quicker than anyone had a right to expect, the Mulsanne Turbo proved to be a handful. Autocar testers gave the car a meagre two stars for handling in its early road test, pointing out that the Turbo was now asking “questions it was never intended to answer” of the chassis. The magazine continued with its criticism: “To be blunt, throw the Turbo into even a smooth consistent-radius bend with enthusiasm and you’ll wish you hadn’t.” The same testers reckoned the steering was too light and devoid of feel, while the understeer and body roll built up alarmingly at even modest speeds. They considered that when pressed, the car tended to float and lurch its way around tighter bends, although they did concede that few Bentley drivers would hustle this hard. In the wet they found that the dogged understeer could turn into tail-out oversteer all too easily, pointing out that if Jaguar could make a big, powerful saloon handle neatly, then so should Rolls-Royce…

The team at Crewe was, as it turned out, acutely aware of the Turbo’s deficiencies in handling, but had simply lacked the resources to develop a revised suspension at the same time as the new engine. Knowing the turbocharged performance would make the headlines, it opted to introduce the new engine first and deal with the consequences later, no doubt knowing that in the real world their customers would seldom explore the car’s cornering limits.

A partial solution came in July 1984 with the launch of the cheaper Bentley Eight, a model intended as a less overtly luxurious and more affordable entry-level offering with more sporting appeal. Tasked with luring younger buyers into the Bentley fold, it offered stiffer chassis settings, which proved that the basic SZ platform could be made to handle confidently… but this remained available only on the Eight.

Marque historians generally credit this to the innate concern for ride quality at Crewe, something that made the engineers forever hesitant of firming up the underpinnings. When John Hollings was replaced by new engineering chief Mike Dunn in 1983, however, he took decisive action. After trying what had been developed as a proposed uprated suspension, he immediately insisted on the settings being stiffened by as much again. The horrified development team duly obliged and turned in a package using a 100% per cent stiffer front anti-roll bar, a 60% uprated rear bar, firmer dampers with uprated rebound, a 50% firmer power-steering set-up and a Panhard rod to reduce sideways movement of the rear subframe. To these changes were added lightweight 15-inch alloy wheels shod with 275/55 tyres and a deeper front spoiler to create the model marketed as the Turbo R in 1985… with that ‘R’ apparently standing for ‘Roadholding’.

Bentley Turbo R

The car was transformed, with Autocar commenting that the Turbo R could now be driven through S-bends much more tidily, while the lift-off oversteer was much reduced. They concluded that the car was now “a marvellous experience to hurry down a truly open, lonely country road… to be travelling so quickly in so big a car.” It wasn’t perfect though, with road testers describing the ride as “surprisingly knobbly” on the optional newly-developed Pirelli P7s, while they also found the steering fidgety on heavily-cambered roads.

The reception of the Turbo R was so positive in Europe that US dealers were soon asking for a Federal-spec version, and so work began in 1988 to make the turbocharged V8 emissions-compliant. This was achieved largely by replacing the Solex carburettor with Bosch fuel-injection, in this case the part-electronic KE-Jetronic system that was already used by Ford on its turbocharged Escorts.

The opportunity was taken to revise other aspects of the installation too, with a new ignition set-up effectively working as two separate systems complete with two coils and two distributors. An air-to-air intercooler was added to the mix and suddenly the engine was not only US-market compliant but also boasted 330bhp.

Better tyres also allowed the speed limiter to be removed and the big Bentley could now top out at 143mph. A slight icing on the cake – and it was very slight – was that the injected turbo engine was more fuel-efficient than the carb-fed unit, although economy was still in V12 Jaguar territory at 15mpg. The car was duly released on to the American market in 1989 and from here the Bentley brand didn’t look back.

June 1988 saw the Turbo R receiving the new front-end style applied to the rest of the Bentley range, with four circular lamps replacing the original rectangular units, while in 1989 (for the 1990 model year) an adaptive damping system was added, firming up the dampers according to how hard its sensors judged the car was being driven.

Bentley Turbo R S

In 1990, the three-speed GM gearbox was replaced by the more modern 4L80E four-speed version, while for the 1994 model year the ultimate turbocharged SZ Bentley was released: the Turbo S, boasting a 408bhp development of the turbo V8 that produced a colossal 590lb.ft. torque at 2000rpm, making the car good for 155mph. This limited edition of just sixty cars was largely built to prove the engine destined for the Continental T coupé.

For the 1996 model year, the regular Turbo R was uprated to 385bhp at 4000rpm and 553lb.ft. of torque at 2000rpm, courtesy of a water-to-air intercooler (‘chargecooler’) and Zytek engine management system allowing ‘mapped’ control of fuelling, ignition and boost. More modern 17-inch wheels were also introduced at this point.

The standard-wheelbase car was discontinued in 1997 and the sole turbocharged model was the long-wheelbase Turbo RL. Later in the year, the Turbo would appear in its swansong iteration: the Turbo RT, effectively combining the Turbo RL body with the Continental T-specification engine rated at 400bhp. The last of the turbocharged SZ models would leave the Crewe factory in December 1997 as the premises were prepared for the launch of the Arnage.

The success of Bentley’s new turbocharged line of the 1980s and ’90s had taken Rolls-Royce management completely by surprise, with demand building quickly even for the somewhat flawed original. Between 1982 and ’85, a total of 520 Mulsanne Turbos were produced, a figure that jumped to 4657 for the Turbo R, followed by 1508 examples of the Turbo RL. Such was the impact of these performance models, by the mid-1980s Bentley-badged cars were outselling Rolls-Royces for the first time since the 1950s.

Evolution

The production version of the turbocharged engine was very similar in principle to the installation engineered by Ralph Broad and his team on that first Silver Shadow prototype, albeit refined in detail. Central to the installation was a massive Garrett AiResearch T04B turbocharger sited on the offside of the engine bay. The more elegant solution with a vee-configuration engine is to use a pair of smaller turbos but, despite the bulk of the car, the underbonnet space was too cramped to allow this, hence the use of a larger single unit.

The turbo was mounted in the offside of the engine bay, fed directly from the exhaust manifold of the right-hand cylinder bank and with a crossover pipe feeding it from the nearside bank. The installation was a ‘blow-through’ type, with the Solex carburettor mounted inside a hefty cast aluminium airbox that was bolted closed around its perimeter to maintain the 7psi boost pressure. What the modern car tuning world now refers to as a dump valve was mounted on the side of the air box to vent boost air back into the intake side of the compressor when the throttle was snapped shut.

Boost control was achieved via a mechanical wastegate, which used an unusual activation method, being operated by vacuum from the pump which also supplied the cruise control bellows, according to a signal from the electronic speedometer. This was set to reduce turbo boost above speeds of 135mph in the interests of preserving the tyres.

Over-boost protection was further ensured by the boost recirculation valve automatically opening if boost pressure exceeded 8psi. A high-pressure Bosch fuel pump was used to ensure that fuel pressure was always 4psi above the pressure inside the sealed airbox, in order to prevent fuel being blown back out of the carburettor under full boost.

Turbocharged L-Series V8 in the Bentley Arnage T

In the interests of reducing lag and detonation under boost, the turbocharged engine was based around the lower 8.0:1 compression unit used for US-market cars and ran special aluminium pistons with steel inserts to counter the effects of differential expansion between the pistons and cast iron cylinder liners. Uprated inlet valves and valve springs were also fitted, as was an oil cooler. To further guard against the damaging effects of detonation, a Lucas electronic ignition system was used which incorporated a knock sensor to retard the timing by as much as 8 degrees.

Elsewhere, a larger-diameter exhaust was fitted, complete with twin tailpipes, and the torque converter in the GM gearbox was uprated to a six-bolt fitting. A taller final drive was also fitted in conjunction with uprated rear axle componentry, including 34mm halfshafts, larger CV joints and sliding spline hubs.

With Bentley under Volkswagen control from 1998, it was keen to remove its reliance on BMW, which supplied its 4.4-litre twin-turbo V8 for the new Arnage. The surprising solution was to adapt the Arnage to take the traditional ‘six-and-three-quarters’ Rolls-Royce V8 that was still in production for the Azure and Continental in an emissions-compliant specification.

Rather usefully, production had been outsourced to Cosworth, which in September 1998 was also acquired by VW Group and operated as part of Audi. The company took the opportunity to extensively revise the engine and it was duly fitted to the Arnage (along with the older four-speed GM gearbox), the revised car being badged Arnage Red Label. The engine was upgraded at the same time, now producing a colossal 616lb.ft. with a single Garrett turbo.

The last hurrah for the turbocharged L-Series – the Bentley Mulsanne

Development didn’t stop there. In 2002, the long-wheelbase Arnage RL debuted a more heavily reworked version of the L-Series, the version initially employed in the Red Label having been rather rushed into production as a stop-gap measure. This time more than 50% of internal components were modified, while the engine management was swapped from Zytek to Bosch Motronic and the big single Garrett T4 turbocharger was replaced by two smaller T3 units. The end result was 399bhp and 616lb.ft. torque.

This engine was fitted to the regular Arnage from 2002, in which form it was marketed as the Arnage R, alongside an uprated version badged as Arnage T – the latter featuring 459bhp and an eye-watering 645lb.ft. of torque. It didn’t end there for the old V8, however, as the Garrett blowers were replaced by a pair of low-inertia Mitsubishi units in 2007; a modern six-speed ZF transmission replaced the old GM four-speeder and the engine was now at 6761cc, good for 454bhp and 645lb.ft. in the Arnage R, and 493bhp and 738lb.ft. in the Arnage T.

The Arnage disappeared in 2009, but the L-Series kept on going, finding its way under the bonnet of the new-generation Mulsanne in 530bhp form, driving through a paddle-shifted eight-speed ZF gearbox.