We take an in-depth look at the Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow – the legendary saloon that reinvented the best car in the world

Words: Paul Guinness

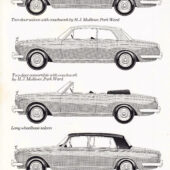

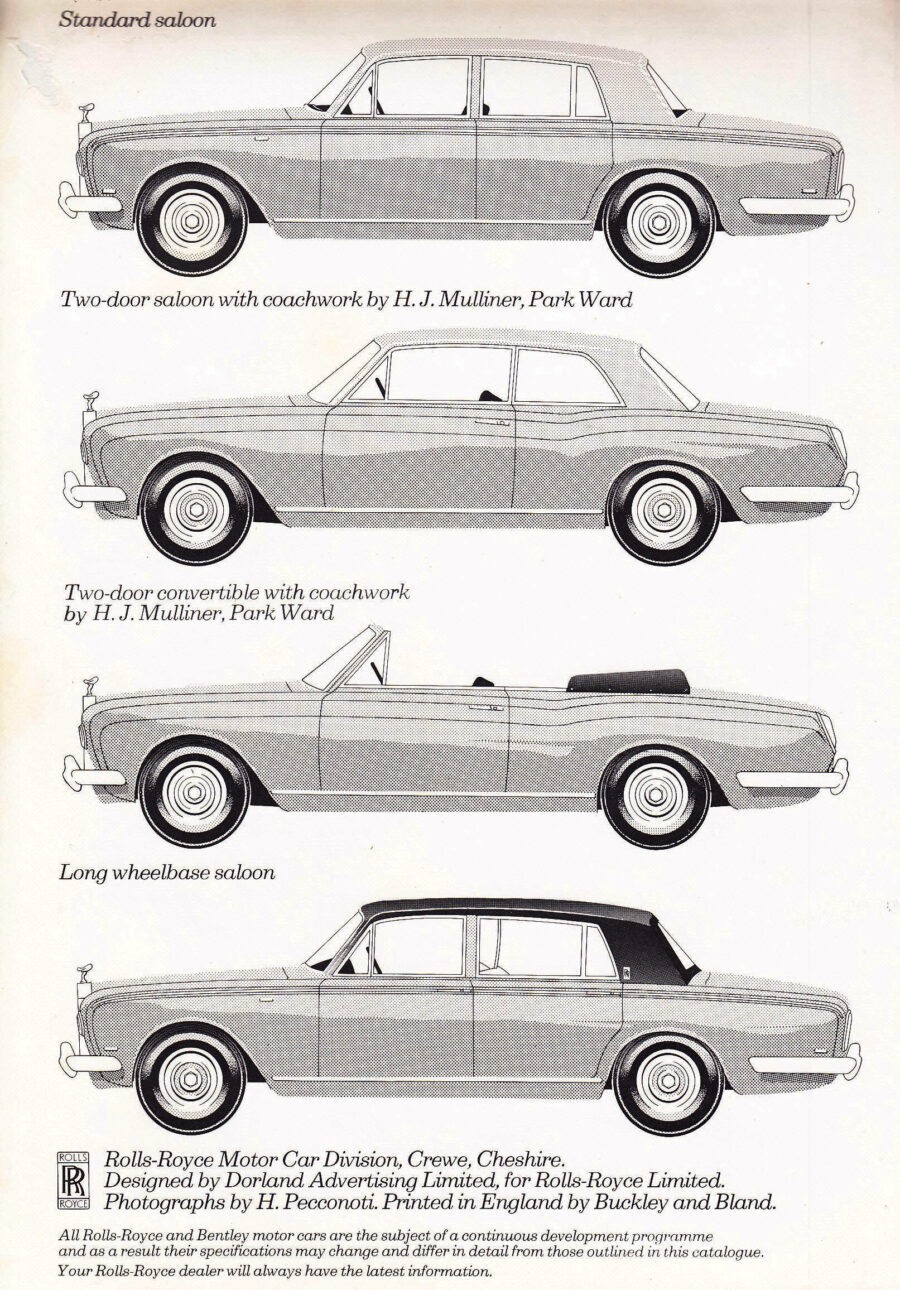

The new Silver Shadow shocked onlookers when it arrived in 1965, grabbing attention not only for its drastic change of style compared with its Silver Cloud predecessor, but also for its levels of hi-tech modernity. Moving Rolls-Royce technology forward in such a profound way enabled the Silver Shadow to enjoy an extended career, with the four-door saloons remaining in production for an impressive 15 years – and their two-door derivatives for even longer.

Rolls-Royce had, of course, enjoyed considerable success with three generations of Silver Cloud – and Bentley S-series derivatives – throughout its decade-long production run. Launched in 1955, here was a car that stayed true to tradition, with its separate-chassis layout enabling Britain’s dwindling numbers of specialist coachbuilders to offer their own bespoke versions. There were modern touches to the Silver Cloud saloon’s aesthetics when it first went on sale, moving Rolls-Royce and Bentley successfully on from the previous Silver Dawn and R-Type era. But car design was evolving rapidly by the start of the 60s, which meant that Rolls-Royce’s chief stylist, John Blatchley, faced a dilemma when it came to creating a Silver Cloud successor.

Even at the upper end of the new-car market, there was a noticeable shift in demand. There would always be wealthy buyers who wanted – and could afford – the ultimate in traditionalism and prestige, which explains why Rolls-Royce continued to enjoy steady demand for its 1959-on Phantom V limousine. But as the 1960s dawned, John Blatchley knew that a successor for the Silver Cloud family needed to cater for a new breed of buyer – the owner-driver who didn’t employ a chauffeur. The newcomer needed to offer the kind of luxury that a Rolls-Royce always should, albeit in a slightly more compact, more manoeuvrable package.

Blatchley also knew that the way the car was built needed to change, as the world was moving away from the separate-chassis layouts of old. The use of monocoque construction might have caused consternation among Britain’s traditional coachbuilders, but it was a must for any new Rolls-Royce that needed to bring extra sales and increased profits to the car-building side of the business. Adopting a modern monocoque layout would enable the new Rolls-Royce to be both lighter and smaller than the Silver Cloud, which in turn would have an effect on both performance and fuel economy; and it would enable Rolls-Royce to build in larger numbers than before.

What became the Silver Shadow of 1965 wasn’t just modern in terms of its construction, of course. It also needed to offer a smoother ride, much-improved handling and more stability at high speed than the Silver Cloud, hence the adoption of fully independent suspension. And with Citroën being world leaders in terms of suspension technology, Rolls-Royce wisely chose to licence the French firm’s hydropneumatic system, albeit redesigned at Crewe to incorporate conventional coil springs. The hydraulics provided self-levelling to maintain the car’s ride quality irrespective of load, as well as powering its four-wheel disc brakes to ensure reassuringly strong stopping power.

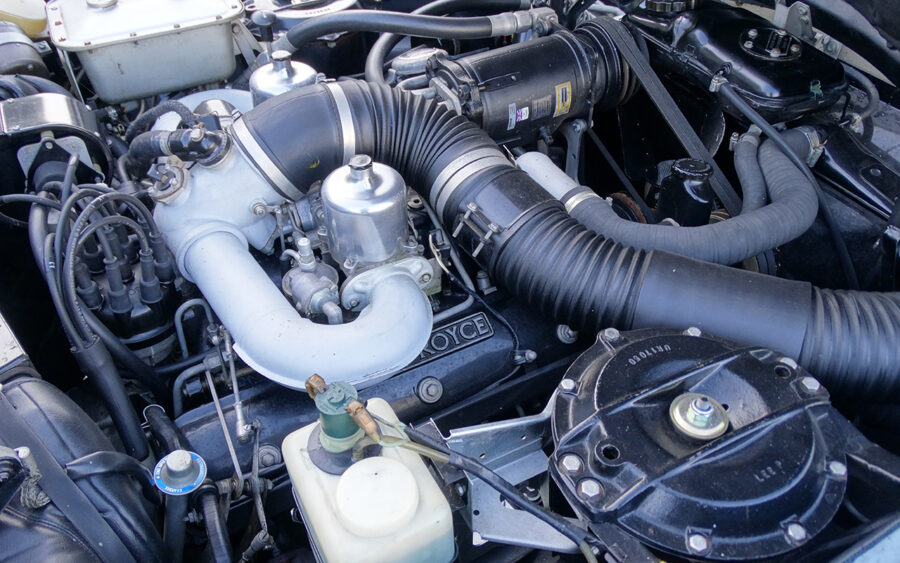

One of the few elements of the Silver Shadow that was carried over from the Silver Cloud III was its 6230cc V8 – a unit that was capable of endowing the smaller, lighter newcomer with superior performance compared with its predecessor. In every other respect, however, the Silver Shadow was a genuinely new design, hailed as “the most radically new Rolls-Royce for 59 years”’. Indeed, not since the original Silver Ghost had there been a Rolls-Royce so genuinely advanced compared with the competition.

Work on a successor to the Silver Cloud began while that car was still in its infancy, with John Blatchley focused on the need for modernity: “Styling this car was very much an architectural exercise… the specification demanded it be lower, narrower and shorter with more luggage space and a bigger petrol tank. My biggest challenge was getting all this paraphernalia, plus passengers, into a car that still looked right.”

Prototypes began to appear in the late 1950s and early 60s, codenamed Tibet (for the Rolls-Royce) and Burma (for the Bentley), the original plan being to make the Bentley the smaller of the two. Even at that early stage, the final shape of the Silver Shadow was beginning to emerge, although the wraparound screens and reverse-angle rear door windows made those initial cars look dated compared with the eventual production model.

The grille treatment of the early prototypes was also controversial, as Blatchley experimented with numerous options (including a full-width grille design incorporating quad headlamps) before deciding on the final version. Martin Bourne, another member of the Rolls-Royce design team from 1959, recalled the many changes made during the Silver Shadow’s early development: “Hardly a day went by when some small detail of its appearance wasn’t being considered”.

Rolls-Royce was also working with the British Motor Corporation (BMC) at this time, the idea being to adapt one or two of the bigger company’s models into a higher-volume Bentley employing Crewe’s 4.0-litre, six-cylinder F60 engine. And so while Blatchley and his team worked on development of the Silver Shadow, he also created a front and rear restyle of the Vanden Plas Princess 3 Litre (codenamed Java) to accommodate a Bentley grille between stacked quad headlamps. This eventually evolved into Java 3, a concept with definite overtones of the Silver Shadow. In the end, however, as we revealed in last issue’s in-depth look at the relationship between Rolls-Royce and BMC, the idea of a BMC-based Bentley came to nothing.

The Silver Shadow made its motor show debut at Earl’s Court in the autumn of 1965, with Autocar magazine explaining that a “new Rolls-Royce is an event of a decade”. It hailed the newcomer as “the most advanced and intricate car the company have introduced” thanks to such headline features as monocoque construction and that all-independent self-levelling suspension. The Rolls-Royce stand of ’65 featured three examples of the Silver Shadow, finished in Shell Grey, Regal Red and Dawn Blue.

Members of the motoring press were highly impressed with the newcomer, of course, with Basil Cardew of the Daily Express describing it as “smaller, roomier, lighter, swifter” than its predecessor. John Blatchley’s brief that the Silver Shadow should be lower, narrower and shorter than before (the Silver Cloud was three and a half inches wider and seven inches longer), whilst offering more space for people and their luggage, had been well and truly delivered.

How would the Rolls-Royce and Bentley fans of old take to such an advanced design, though? Bentley Drivers Club president Stanley Sedgwick borrowed a new T-series in 1966, and was immediately impressed: “I accepted the design of the body for what it was. I liked it and I think the S-Types really did look dated beside the car. The more I saw of the car, the more I considered it better-looking than any of its contemporaries.”

There were inevitably complaints from the company’s more traditionally-minded clients, some of whom couldn’t initially accept the Silver Shadow’s modernity, not least its lack of a separate chassis. But in much the same way that the new Rolls-Royce Cullinan of 2018 divided opinion (yet attracted large numbers of orders from new customers even before going into production), there were enough well-heeled luxury car buyers willing to give the Silver Shadow a chance – ultimately ensuring it was the most successful individual Rolls-Royce model of the 20th century.

The standard Silver Shadow saloon did exceptionally well for itself, surviving for a decade and a half before finally giving way to the new Silver Spirit of 1980. Throughout that time, however, Rolls-Royce carried out innumerable upgrades and improvements to ensure it stayed ahead of the luxury car pack.

Many of these changes were subtle, such as the early adoption (at the end of 1965) of a lighter brake pedal movement, while October 1967 saw a Saginaw power steering pump replacing the original Hobourn Eaton type, complementing the Saginaw recirculating ball steering system that was fitted to the Silver Shadow. At the same time, the car’s opening front quarter light windows were changed to fixed units, while in 1968 the Silver Shadow received a revised handbrake, higher-ratio steering, an uprated front anti-roll bar (as well as a rear anti-roll bar for the first time, although not on US-spec cars) and the latest GM400 automatic transmission from General Motors.

Rolls-Royce made a habit of improving on what had already been developed by other manufacturers, of course. Its use of monocoque construction wasn’t exactly an industry first, for example, yet the Silver Shadow’s bodyshell was widely recognised as the stiffest of its kind at the time; and while the company took the sensible approach of licensing Citroen’s suspension technology, it found ways in which it could be upgraded to suit the company’s exacting standards. And so it was with that latest automatic transmission, as Malcolm Bobbitt explains in Rolls-Royce Silver Shadow, Bentley T-Series, Camargue & Corniche (Veloce Publishing): “Although the GM400 gearbox was brought-in direct from America, the electric selector actuation was not part of its specification and this, therefore, was added at Crewe. Rolls-Royce was the only manufacturer to fit electric actuation to this type of gearbox – which allowed the lightest finger-tip control – and whilst such cars as the Cadillac were fitted with the same unit, ratio selection was operated manually.”

Other relatively early changes to the Silver Shadow included the deletion of self-levelling front suspension in 1969, which might have seemed like a retrograde step at the time. In truth, however, the self-levelling front end had relatively little work to do, and its deletion actually managed to improve the car’s handling and steering (which some testers had found to be a little vague). The biggest upgrade at the end of ’69, however, ready for the 1970 model year, was the introduction of the latest 6750cc version of the venerable L-series V8 engine, created via a redesigned crankshaft, which in turn lengthened the stroke. Although Rolls-Royce refused to disclose any power or torque figures, it was estimated that the Silver Shadow now had somewhere in excess of 200bhp at its disposal.

The difference in driving style was immediately noticeable by all those who tested the car, as Malcolm Bobbit explains in his Silver Shadow book: “John Bolster, testing the 6.75-litre-engined Silver Shadow for Autosport in December 1970, was impressed at how much low-speed torque had been improved. Overall speed had also increased, and he found the car easily achieved 118mph.”

The process of improving the Silver Shadow continued unabated, although disaster occurred in 1971 with the collapse of Rolls-Royce following difficulties with its aero-engine division. The appointed receiver realised the importance of ‘business as usual’ for the car-making side of the company, however, and ordered that production of the Silver Shadow should not be affected.

As part of the restructuring, the car-making division was sold off in 1973 as Rolls-Royce Motors, but this was something of a double-edged sword; the firm was now free from the risk of being dragged down by the troubles of a parent group, but resources were much more slender. Although ideas for a Silver Shadow replacement had been part of management discussions for some time (the original plan being for the car to enjoy a ten-year production run), its eventual successor wasn’t to appear until the start of the 80s – which meant extending the life of the company’s best-selling model.

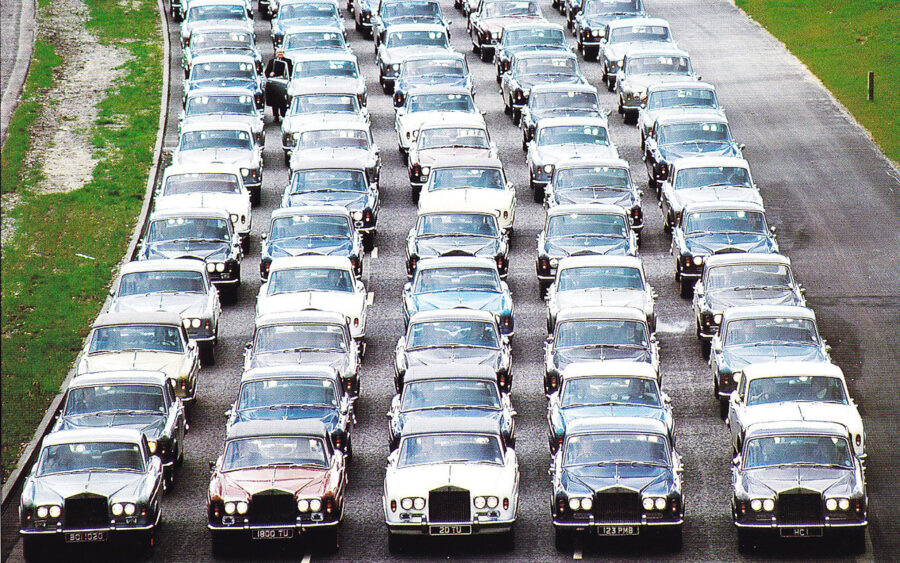

Indeed, sales of the Silver Shadow held up very well once the company was reconfigured as an independent car manufacturer, with 2720 Rolls-Royces being built in 1973 – up from just over 2000 per annum at the start of the decade. But it was obvious that a facelift would be required at some point if the Silver Shadow was to retain its crown as the best car in the world, hence the announcement of the Series II in February 1977.

The most obvious visual changes included plastic-faced alloy bumpers with polyurethane side pieces, while below the front bumper was a spoiler (aimed at improving high-speed stability) and a pair of front fog lamps. Inside the car, the Silver Shadow II boasted a new-look fascia with revised instrumentation, while the air conditioning had been upgraded to a split-level system. Most important of all, however, was the adoption of rack and pinion steering and a modified suspension system, ensuring that the Silver Shadow II offered the kind of sharpened-up handling and more precise steering that luxury car buyers of the late 1970s expected.

Although not strictly a Silver Shadow derivative, the new-for-1975 Camargue (above) shared essentially the same floorpan. It appeared nine years after the debut of the last two-door Rolls-Royce (the Silver Shadow Mulliner Park Ward two-door, later renamed the Corniche), and was certainly one of the more controversial members of the clan thanks to its distinctive styling by Pininfarina.

It was also one of the most expensive cars on sale in the UK, and remained so throughout its career. By 1980, for example, a brand new Silver Shadow II would have set you back £41,960, at a time when the hardtop Corniche could be had for £62,479. But both cars looked almost bargain-like compared with the Camargue, which forty years ago carried a list price of £76,120.

Rolls-Royce described the Camargue as an “elegant and sophisticated two-door saloon of exceptional grace and beauty”. By the time the last Camargue was built in 1985, however, a mere 530 examples had been sold worldwide – reinforcing its reputation as one of Rolls-Royce’s most exclusive models.

Production of the Silver Shadow officially ceased in late 1980 (although some cars weren’t despatched from Crewe until early the following year), at a time when Rolls-Royce was preparing itself for the launch of its successor. What had been a hugely successful model for the company was finally being consigned to the history books, although its Corniche convertible cousin was scarcely halfway through its production run by then. During its 15-year career, the Silver Shadow had gone from being a cutting-edge design packed with modernity to the highly respected elder statesman of the luxury saloon world. It left the automotive stage with dignity – and remains the most prolific classic Rolls-Royce to this day.