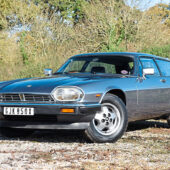

We tell the story of the XJ-S based Lynx Eventer, one of the best-loved shooting-brake estates ever made

Words: Sam Skelton

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that those with the money to buy upmarket cars like the idea of a sports estate. Prince Philip loved his Triplex GTS Scimitar, the car that inspired the Scimitar GTE – and his daughter Princess Anne has had a stream of GTEs since the model was first announced. David Brown’s wealthy mates all wanted shooting brakes based upon the Aston Martin DB5, and Saudi Princes love their Turbo R based Jankel Val d’Iseres. It seems surprising, then, that the closest Jaguar came in the same era was the E-type hearse from 1971’s Harold and Maude.

By the time of the XJ-S, coachbuilding had reached a lull – with monocoque construction putting an end to many traditional techniques and the tuner car renaissance of the 1980s yet to take hold. But Guy Black and Roger Ludgate had founded Lynx Motor Company seven years earlier, in 1968. Black was former Chief Production Engineer at Weslake Engineering, and Lynx was initially intended as a service and maintenance provider for owners of pre and postwar racing cars.

In 1974 it launched its first D-type replica, followed by a replica of the C-type. It would then turn its attention to road cars, spotting in the XJC an ideal candidate for open conversion and engineering a rather beautiful four-seat cabriolet from the two door XJ. Once production stopped, Lynx would put the knowledge garnered from this project into practical use on the XJ-S, ensuring that those saddened by the demise of the V12 E-type would still be able to buy an open Jaguar if they could stretch to the cost of conversion.

The workshop in St Leonards on Sea enjoyed a small but steady stream of customers, and the quality of the work meant that many who had bought a racing replica would return for a road car too.

Launched in 1979, the XJ-S Spyder was seen by many as a success – removing the most contentious part of the XJ-S shape, improving visibility, and with no compromise to interior space or style with the hood up or down. Black – with colleague Chris Keith-Lucas’s input – had even managed to retain the rear seats, a practicality sacrificed in many open conversions of 2+2 GTs. Inevitably though, and with news of an in-house open XJ-S on the horizon, Black soon turned his attention to other possible adaptations of the XJ-S theme. Chris Keith-Lucas would once again help translate Black’s ideas into metal.

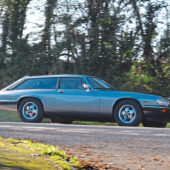

A sporting estate seemed like an obvious winner – a model type that history had shown was popular enough to sustain production, and one that it was highly unlikely Jaguar would adopt for production itself. However, it would take just as much work as the Spyder to create. While the car wouldn’t need the extra stiffening that roof removal had necessitated, it would still need changes in order to be useful. For one, in an XJ-S the fuel tank sits atop the rear axle behind the seats, and if a sports estate were to have folding seats for an extended luggage bay, the fuel tank would need to be re-sited. Consideration would also have to be given to style, in order to ensure it looked like an in-house effort rather than some back street lash-up.

To produce an Eventer, Lynx started with an XJ-S – at launch, this would have been a V12, but with the launch of the 3.6 the conversion was made available on both models. It wasn’t specific to new models, either – if you wanted to convert a used XJ-S, Lynx would have accommodated. Over time this would also expand to cover the subsequent 6.0 and 4.0 models, and the XJR-S.

The rear bulkhead of the donor car was modified, along with the rear section of the roof – the whole roof from the 18th car onwards. The fuel tank was removed, and a replacement specially shaped unit fitted around the spare wheel laid flat on the boot floor. A new false floor was fitted at axle tunnel height, ensuring not only room for the fuel tank beneath but a flat load bay floor from the tailgate forward, and a new rear seat back was fitted which would allow for the rear seats to fold for longer loads. In total, the load space available would come to six feet in length, even if the height of the XJ-S rather restricted you as to the types of furniture that might be carried.

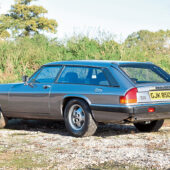

New inner and outer panelwork was fitted to the rear of the car, and uprated rear springs were fitted to cope with the altered centre of gravity and with the potential for loads heavier than might be carried in the standard car. A Citroën Ami 8 Berline rear screen was used – cleverly integrated into a tailgate which was designed from behind to resemble the original. Some Eventers also featured revised rear seat positioning and recessed rear floors for 2” extra legroom and foot space under the front seats – but these options weren’t available on the first conversions, which retailed at £6950 plus VAT. Externally, Lynx would respray the roof and rear wings to ensure that the conversion blended in, and a full respray was a cost option.

And the results were impressive – impressive enough, according to Motor Sport magazine, to have received tacit approval from Jaguar itself. Sir John Egan was less complimentary than the report would suggest, though – having first seen the car at Jaguar Day in 1982 and not having been told that the car was under development. This scuppered Lynx’s original plan – to sell the concept to Jaguar and build it under licence for them, rather than to market directly to customers. When Sir John refused to collaborate, and customers showed interest, Lynx almost felt obliged to offer the Eventer as an aftermarket conversion and a flurry of orders soon followed. The factory would go on to honour the original warranty on all unmodified components.

Egan has been quoted as saying that he thought the car looked “a bit like an upmarket Reliant Scimitar” – not that this is necessarily a bad thing in mind of the clientele that Reliant could claim.

And that wasn’t the only area in which Lynx outdid Reliant. Seats up a late Scimitar SE6B could claim 20cu.ft of carrying capacity, which doubled to 40 cu.ft with the seats down. With almost 4 cu.ft more with the seats in place and an extra 2 cu.ft with the seats down, the Eventer was more commodious than the Reliant as well as being more upmarket.

The first Eventer prototype was presented to the press in August 1982 – at this stage, the car was not fully trimmed, but reactions were still positive and the first production models would be built at the end of the year for 1983 delivery. Contemporary testers praised the car’s finish and refinement, commenting that it was plausible that the car had left Jaguar that way in the first place and drawing attention to the lack of wind noise and rattles. Patrick Motors Group was the official selling partner and contributed toward the Eventer’s development costs, while Spink of Bournemouth and Reeve and Stedeford would also become approved agents.

Conversion was quoted at 14 weeks – but could take longer – and each car was built to an individual customer’s desired specification. In two cases, this included the omission of rear seats in order to circumvent import duty rules in Norway. Upon delivery, the customer would be presented with a photo album detailing the conversion process from start to finish.

Over 19 years, just 63 Eventers were produced; the last conversion undertaken to a Jaguarsport XJR-S in 2002. By this time, costs had risen – and the original £6950 plus VAT of 1983 had become £49,500 for the privilege of conversion. While Lynx teased the concept of an XK8 or DB7-based estate as its next project, neither would come to fruition.

The Lynx Eventer spawned a number of copycats. Having seen the success of the Eventer project, German Jaguar tuners Arden decided in 1987 that a sports estate would fit well with its plans for the XJ-S range. Arden had already expanded the XJ-S portfolio by engineering a full convertible to sit alongside Jaguar’s cabriolet, and by adapting the coupe to lose its buttresses in the form of the Daimler-like Arden AJ6.

In 1987 it announced the AJ3 – a sports estate that bore more than a passing similarity to the Lynx though with detail changes such as internal tailgate hinges. Arden literature showed just one example, but the company claims a total of five were planned.

However, documentation found in Lynx’s records held by Pascal Mathieu of the Eventer Preservation Society would appear to suggest that the Arden AJ3 was in fact an Eventer underneath. Arden had ordered chassis 24 in 1984 before cancelling the order. Three years later, Lynx was approached – supposedly on behalf of a German training college – asking for a conversion kit to allow students to rebuild a damaged XJ-S as an Eventer. After several rebuttals, Lynx relented – the money was handy, and it meant that a very pushy customer was dealt with. This kit of parts – number 32 – would subsequently be shown to have been bought by an Arden sales manager masquerading as a teacher and built into the AJ3, as part of a reverse-engineering process.

A deal was made whereby Arden would retain the car it had built and future AJ3s – of which there was only one, chassis 52 – would be based on completed Lynx cars. Chassis 32 would be offered for sale for the first time after Lynx had been wound up in 2012.

The second copycat really was a copy, rather than a car built with Lynx parts – using GRP panels moulded from an original Eventer. Lynx threatened to take the manufacturers of the French Ateliers-Reunis XJ-S Break de Chasse to court, but the company went bankrupt before Lynx had the chance. These cars also used windows designed for the Eventer, and sourced directly from the glass manufacturer. It’s believed that 11 were produced but only six are known.

A sole car was also made in Belgium, and was said to have been built to an equal standard as the Lynx originals. Built by Ortoni for classic car salesman Gerard Dulait, it was commissioned because Dulait felt that the quality and waiting list length for a genuine Eventer were inadequate. This car was believed to be a genuine Eventer for many years, and these facts come via the Eventer Preservation Society.

Lynx Eventer No. 47 was to have been the start of a special partnership. And in 1990, when an XJ-S V12 was £34,200 and a completed Eventer in the region of £47,000 plus extras, the project that car 47 would have kick-started would have been a series of 20 £100,000 specials. For that money, they not only had to be good, but they had to carry the right name. And the name they were destined to carry was ‘Disegno di Paolo Gucci’.

Lynx Eventer No. 47 ‘Disegno di Paolo Gucci’

Paolo Gucci had once been vice-chairman of the family fashion brand that bore his surname. But a series of questionable business decisions – including, inexplicably, the launch of his own rival Gucci fashion label while heading up the existing Gucci brand – led to his dismissal from the family firm, a lawsuit from his father, and his subsequent revenge in reporting senior family members for tax evasion.

One day in late 1989, the St Leonards on Sea factory was visited by Paolo Gucci, who asked Lynx for something simple – a Gucci interior in an Eventer. Lynx chief trimmer Phil Gould was entrusted with the design concept, visiting Gucci to discuss interior concepts and materials. Gucci wanted crocodile-skin, but this would be replaced with embossed calf leather.

There was also to be stained elm woodwork with chevron marquetry, in an extended application compared to factory cars, there would be two tone paint, US-style twin headlamps and big wheels. He also wanted the car to be finished by the Geneva Motor Show, just 12 weeks away when a standard Eventer took fourteen.

A used example was sourced – there being no time to order a new one – and work began. Often, the team would put in 15-hour days, mindful of the deadline – and all other Lynx projects were postponed until the car was finished. The last bits of trim were completed just before the car was driven to Geneva – as was the unique instrument pack, with needle gauges replacing the standard car’s minor instruments. The steering wheel and gear selector would both feature semi-precious lapis lazuli stones.

Sadly, the car would be vandalised at the show by lawyers acting for the House of Gucci – gouging the Paolo Gucci badges from the wings when Lynx refused to take the car off show. By the second day, the Gucci stand had been re-dressed as a Lynx stand, and legal battles over Paolo’s right to use the Gucci name meant that the car remained a one-off. Sold by Paolo Gucci in 1990 in order to stop it being considered an asset in a divorce case, he was subsequently unsuccessful in attempts to buy the car back. It resurfaced in 2014, and has since been fully restored.