With the Italian-styled Camargue having spent too long in the shadows, the model has now come into the limelight as a rare and stylish classic

Words: Sam Skelton

Search the internet for information on the Rolls-Royce Camargue and you won’t find many positive opinions. You’ll see that it had a starring role in the Top Gear book, Crap Cars, and you’ll find various articles describing it as a lemon, as a mistake. In short, you won’t find much praise. Yet, the Camargue is surely a car that deserves a more positive press, particularly as one of Rolls-Royce’s rarest models of the last half a century – with just over 500 examples sold between the model’s debut in 1975 and its demise eleven years later.

The Camargue has always suffered at the hands of its critics primarily for three reasons. First, it was vastly expensive – and when the Corniche did a similar job at the same time, relatively few buyers were willing to pay the extra. Second, the body was a little heavy handed to some eyes. And third, as so few drivers have experienced the joy that a good Camargue can bring, it’s the screaming masses that seem to have the upper hand. Happily, however, the market has started to wake up to the Camargue, with values now strengthening as a result.

The Camargue project was initially developed as a replacement for the Silver Shadow MPW two-door, a Silver Shadow-based coupé. But the company’s financial difficulties and subsequent launch of the mildly updated Corniche proved one thing: if the newly rebadged Corniche could save the company from bankruptcy, there was life in the old car yet. The Camargue project was therefore repositioned as a range-topping personal car, to sit above the Corniche in the range and to give the company a halo model that could be built to maximise profit.

Named after a region of French marshland bordered by the Mediterranean, the Camargue was targeted at the kind of jetsetters who might have had a holiday home in Monaco, or for whom international travel was a way of life. The aeronautical world could offer Concorde, and Rolls-Royce presented the Camargue as precisely the kind of car in tune with that supersonic lifestyle.

You certainly needed a bank balance to match such a lifestyle if you were to afford a new Camargue, a model that cost £29,250 upon its launch in 1975 – at a time when the average wage was £72 per week and the average house cost a smidge under £13,000. Indeed, the Camargue’s list price would have bought you a usefully-sized detached dwelling within the London commuter belt, such was its upmarket status.

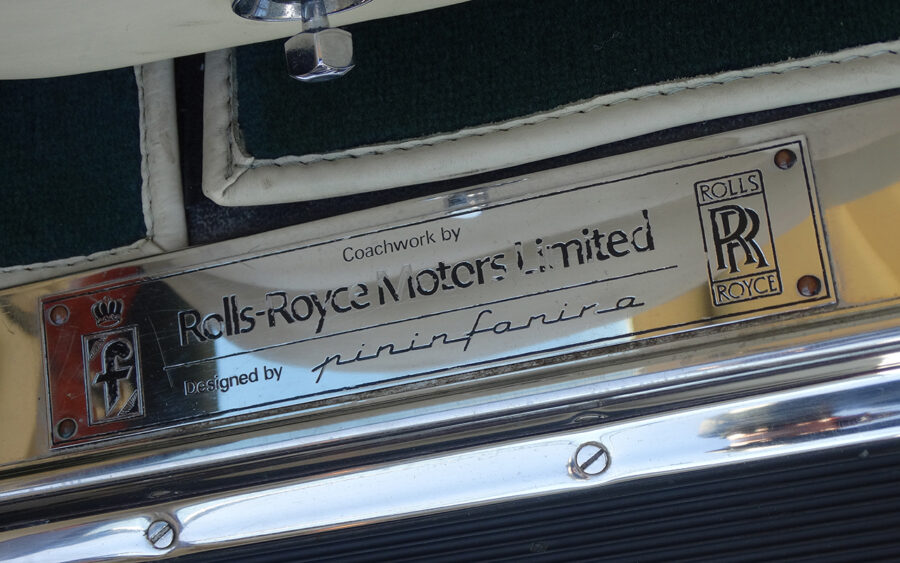

It shouldn’t be a surprise to learn that such an extravagant vehicle had its roots in a one-off project developed for the aristocracy. The Bentley T-series coupé created by Pininfarina in the mid-1960s for Lord Hanson was the spark for what became the Camargue project. That one-off design was finalised and shown at the Paris Motor Show of 1968, attracting the attention of a number of Rolls-Royce bigwigs in the process.

Pininfarina had accepted the commission well aware that it might lead to official work from Rolls-Royce to develop a new Continental; and when Rolls-Royce did approach the famed Italian styling house about a project of its own, the same stylist who had created the Lord Hanson car was set on the job. Paolo Martin was also involved in the design of the original Triumph Spitfire, the Lancia Monte Carlo and the Fiat 130 Coupé; and while elements of the Pininfarina Bentley might have made it into the eventual Camargue, the big Fiat was equally influential upon the final design.

Unlike Rolls-Royce’s internal styling department which prized traditionalism and retained imperial measurements, the Italian design house of Pininfarina reflected continental norms by using metric measurements on design drawings and blueprints. As a result, the Camargue became the first Rolls-Royce to be styled to metric proportions – a fact not lost on its detractors, who suggested that the size of the body was the result of confusion at Crewe between the centimetre and the inch! Other firsts for the Camargue included curved side glass; previous Rolls-Royces had retained flat side windows, but Paolo Martin felt that a range topper should make concessions to contemporary norms.

Martin also inclined the Doric radiator grille forwards by seven degrees (the first time the famous facade had deviated from the vertical), as Pininfarina favoured a sporting stance. The rest of the body was familiar to students of the Fiat 130 Coupé, albeit scaled up to Rolls-Royce proportions. It was less fussy than the Silver Shadow bodyshell, with slab sided flanks, wing tips that met the bonnet rather than rising above it, and a rear end that was elegant in its simplicity. On the face of it, the Camargue’s ’shell had the potential for true beauty, but its size meant that much of the detail became lost and the overall effect was a touch underwhelming to many onlookers.

The Rolls-Royce styling department was not impressed by the Camargue when bodies in white were first seen. The nose – likened by some to the pink Rolls-Royce used by Lady Penelope in Thunderbirds – had been modified last minute, with the grille assuming greater prominence and robbing it of its delicacy. The rear, meanwhile, had its own issues. It was described in Graham Hull’s book Inside the Rolls–Royce & Bentley Styling Department 1971-2001 as “suffering from bad posture”. Its tail-down stance and narrow track made it look ungainly, “as if crushed by a great weight that the self-levelling suspension couldn’t handle”. Where a coupe should be svelte, the Camargue’s external aesthetics left something to be desired.

Inside, however, was different, with the Camargue taking its styling cues from light aircraft rather than following the same pattern that traditional Rolls-Royce buyers expected. There was still walnut, but for safety reasons the veneer was backed with aluminium sheet. The instruments were fitted into black housings as per the average Cessna, and the seats had wider and sportier looking pleats more in the manner of Newport Pagnell than Crewe. The overall effect was rather special; the interior of the Camargue would have been perfect for a new flagship Bentley sports coupé, despite being officially only sold as a Rolls Royce.

Interestingly, the road-going Camargue prototypes all wore Bentley grilles in an effort to obfuscate the true nature of the car for any press photographers. A single Bentley Camargue was built in 1985 by special request, and was allocated a Bentley chassis number, while others have been converted to Bentley badging and grille design whilst retaining their Rolls-Royce numbers. Originally, the plan was to use the Camargue as the basis for the turbocharging plan – to create a super coupé in the manner of the old Blower Bentleys – but low interest in the Camargue meant that the eventual Mulsanne was felt to be a safer bet as the basis for a range topper.

Under the skin the Camargue was little different from the Silver Shadow upon which it was based. The floorpan was shared, as were the 6.75-litre L-series V8 and GM Turbo Hydramatic 400 three-speed transmission, plus just about everything else down to the differential and suspension. One difference between Camargue and Shadow, however, was the lowering of the Camargue’s compression ratio to 8:1 (in place of the Silver Shadow’s 9.5:1), which meant that four-star petrol became an option where five-star wasn’t available.

A feature shared with later Corniche models and the aforementioned Mulsanne Turbo was the Camargue’s fitment of a Solex 4A1 four-barrel carburettor, a move that increased both power and torque. Although the figures were never officially released, the believed improvement was in the region of 10%, which would have given the car approximately 220bhp.

The Camargue certainly needed that extra power. It was a full ten percent heavier than the equivalent Silver Shadow saloon, carrying an extra 228kg in weight. This meant that despite the extra power, it was no quicker than the saloon which sired it; a top speed of 120mph and a 0-60mph time of 11.3 seconds were almost identical to the Silver Shadow thanks to the newcomer’s increased weight and frontal drag. (The rarity of the Solex carburettors and spares, plus problems with warped carburettor bases, has resulted in many Camargues being converted to the saloon’s twin SUs, causing performance to suffer as a result.)

The Camargue was also notable for pioneering Rolls-Royce’s split-level air conditioning system, which had been in development for a full eight years. The system boasted the power of thirty domestic fridges and was able to split the air temperature by level. Those who wanted cold faces and warm feet rejoiced; and while such systems are commonplace now, that fitted to the Camargue was the first automotive application of its type. The same system later made it into the saloon models via the Silver Shadow II of 1977, and continued without significant change into the Silver Spirit of 1980-on.

At its press launch, the Camargue left some journalists perplexed, not least those from Motor Sport magazine: “Closer examination of the assembled cars greatly disappointed us, for rumours of specification and price had led us to expect a totally new and advanced car. Instead we found that the monocoque shell of this two-door saloon is the only new thing about it, apart from a brilliant, automatic, two-level air-conditioning system, which in any case will eventually be fitted to the other models in the Rolls-Royce range. So what is this grossly expensive motor car all about apart from the exclusivity which its price and low production rate will ensure? The advantages over and above the Corniche are quickly enumerated: that automatic air-conditioning (which, as we’ve said, will eventually be incorporated in all Rolls-Royces), more interior space, including an 8.5-inch increase in rear seat width compared with the Corniche, and an extra 3 cu.ft. of luggage capacity to give an enormous 25 cu.ft. total.”

Fortunately, the press were pleased with how the car drove, citing the better weight distribution afforded by its Pininfarina-designed body and the well-balanced if slightly light power steering. There was no initial understeer, and all who drove the Camargue were impressed by its poise and balance for a car so big and potentially unwieldy. Noise issues caused by stones kicked up into the rear wheelarches and wind noise around the mirrors were felt to be jarring in a car worth the same as five Jaguar XJ12s, however, while the engine was considered intrusive when compared to the big Browns Lane cat.

Motor Sport concluded with the assumption that while it might not sell strongly in the UK, the Camargue would certainly export well – a view that was shared with Rolls-Royce itself, which projected 70% export sales compared with 55% for the standard saloons. The company was bullish about the way the world would take to the car, taking the unheard-of step of raising the price for the US market rather than reducing it in line with the sterling/dollar relationship.

The $15,000 hike was justified by the need to adapt Camargues to meet US regulations for safety and pollution, though Rolls-Royce certainly knew its market. The Camargue could generate profit for the company, and it exploited this in markets where finances flowed more freely. Currency depreciations in the wake of a recession led to large price hikes during the Camargue’s life span, which affected sales – as did the fact that the car had been launched in between two global energy crises.

On the Camargue’s press launch in Sicily, Rolls-Royce Motors’ managing director David Plastow stated: “During the last couple of years we have seen the secondhand prices of Corniche coachbuilt cars reach figures in excess of £20,000, and the clear indication was that the world’s motor market would accept an additional coachbuilt Rolls-Royce provided that it represented in shape and exclusivity a significant advance upon the present coachbuilt cars. Our customers expect the best and they are prepared to pay for it. They are also paying for exclusivity, and thus the Camargue will be coachbuilt in very limited numbers – one per week to start with, rising to two per week by next year.”

It’s perhaps not surprising to learn that clients who favoured customised Rolls-Royces soon took to the Camargue, with a series of cars built and trimmed in ways that would have caused traditionalists at Crewe to suffer internal haemorrhaging. These ranged from the mild to the wild, with companies such as Hooper also quick to seize upon the Camargue as the basis for the ultimate in personal cars. Front spoilers, Parkertex velour trim and additional toys such as televisions were prominent additions to a number of examples.

One noteworthy Hooper conversion was a car known as the Beau Rivage, commissioned and built by Hooper itself for the 1983 Geneva Motor Show. This car was unique and is reputed to have been sold within two hours of the show doors opening. Finished in two-tone Magnolia and Walnut, the interior was finished in Nuella Tan leather with Deep Fawn carpets. Among its additional equipment were a redesigned centre console and a television and VCR, while aspects of the trim were colour coded. The car is believed to survive in enthusiast hands.

Rather bizarrely, one Camargue has even been converted to a hunting vehicle, with cut down flanks, no doors and a raised ride height for when out on safari. By order of an Arabian aristocrat, Franco Sbarro created the machine, featuring an electrically retractable windscreen among its many hunting-related accessories.

The most desirable series Camargues are the special edition models, which began with the Anniversary. A total of 212 Rolls-Royces were completed to commemorate 75 years of the marque in 1979, with each car featuring red badge wording in place of black, plus a plaque on the inside of the glovebox lid. Rolls-Royce had originally intended to use only Silver Shadow saloons as the basis for the Anniversary, but in the end two particularly special examples were built – one based on a Silver Wraith, the other on a Camargue. Registered ONM 265V, this unique car was finished in the one-off shade of Coronation Blue Fire Mist.

The Camargue was also made available in Limited Edition guise, of which just twelve were built. Finished in white with a matching Everflex roof, the Camargue Limited Edition models all featured red leather with red and white trim, colour-coded bumpers and alloy wheels. The Limited Edition batch was completed in 1986, intended to celebrate the 80th anniversary of Rolls-Royce sales in the United States, and was sold exclusively in America. These were the only Camargues to be sold with a name badge – which denoted them as Camargue Limiteds – and were the last twelve Camargues produced. One was subsequently converted by Niko-Michael Coachworks of Port Washington, New York, into a retractable hardtop.

Interest in the Camargue has risen significantly in the last decade, with time and exposure showing it to be the elegant and timeless piece of design it truly is, rather than the gauche irrelevance that so many onlookers have accused it of being over the years. While values continue to climb, however, it is still one of the most accessible of Rolls-Royce’s most exclusive personal models. Camargues don’t often come to market, but when they do you’ll find that between £50,000 and £75,000 is still enough to secure what is arguably the most sporting of all Rolls-Royces assembled at Crewe.